Stories in Stone Cemetery Tour 2023

Posted on June 11, 2023 by Jenny ONeill

TRIPP FAMILY BURYING GROUND

TRIPP FAMILY BURYING GROUND

6 Fallon Drive, Westport MA

Research by Todd Baptista

Saving the cemetery

The Tripp Family Burying Ground was established by Ebenezer Tripp (1710-1791), the grandson of master carpenter John Tripp (1611-1678), who landed at Newport, Rhode Island in 1630 after leaving his home in Northumberland County, England. When Ebenezer died at the age of 81 in 1791, he was buried on a grassy, wooded knoll overlooking what is now Drift Road. Over the next 80 years, more than 50 members of his family and extended family would be laid to rest in the burial ground.

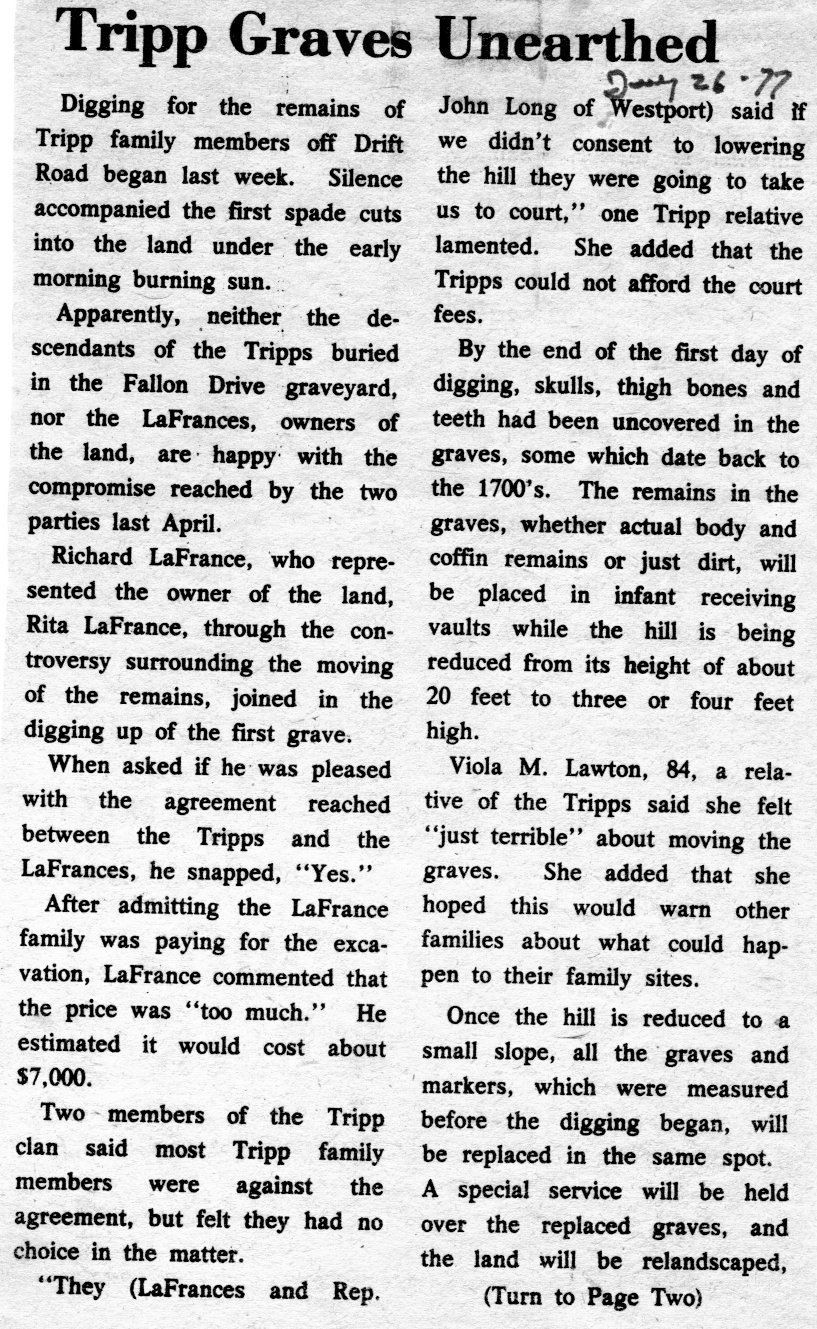

By the 1970s, the cemetery had fallen into disrepair and a new road, Fallon Drive, and a subdivision for a housing development was planned for the area. Permission was ultimately granted to the landowners to relocate the remains of those buried at the site through an act passed by the state legislature in May of 1975.

Subsequently, discussions at Town Meeting and publicity about the cemetery move alerted several generations of Tripp descendants who were unaware of the plan. Among the most vocal of the 30 descendants who opposed the action were Arnold Tripp, Ebenezer’s 5x-great grandson, and his wife, Patricia. Another family member, Norris Tripp, filed a bill calling for a repeal of the original legislative bill and reportedly planned to seek an injunction to prevent work from starting. The landowners acknowledged their mistake in not attempting to locate possible heirs and descendants and soon, both sides, eager to avoid a lengthy and costly legal battle, began working toward a compromise.

Subsequently, discussions at Town Meeting and publicity about the cemetery move alerted several generations of Tripp descendants who were unaware of the plan. Among the most vocal of the 30 descendants who opposed the action were Arnold Tripp, Ebenezer’s 5x-great grandson, and his wife, Patricia. Another family member, Norris Tripp, filed a bill calling for a repeal of the original legislative bill and reportedly planned to seek an injunction to prevent work from starting. The landowners acknowledged their mistake in not attempting to locate possible heirs and descendants and soon, both sides, eager to avoid a lengthy and costly legal battle, began working toward a compromise.

After several months of negotiation, both sides came to an agreement in February of 1977. According to news reports, the LaFrance family paid an estimated $7,000 to excavate the cemetery (about $35,000 in today’s money), remove the eroding hill, and return the remains and the gravestones to their original locations.

Fall River funeral director Mark Bearse oversaw the entire process. “By the end of the first day of digging, skulls, thigh bones, and teeth had been uncovered” one reporter noted. “The remains in the graves, whether actual body and coffin remains or just dirt, will be placed in infant receiving vaults while the hill is being reduced from its height of about 20 feet to three or four feet high.”

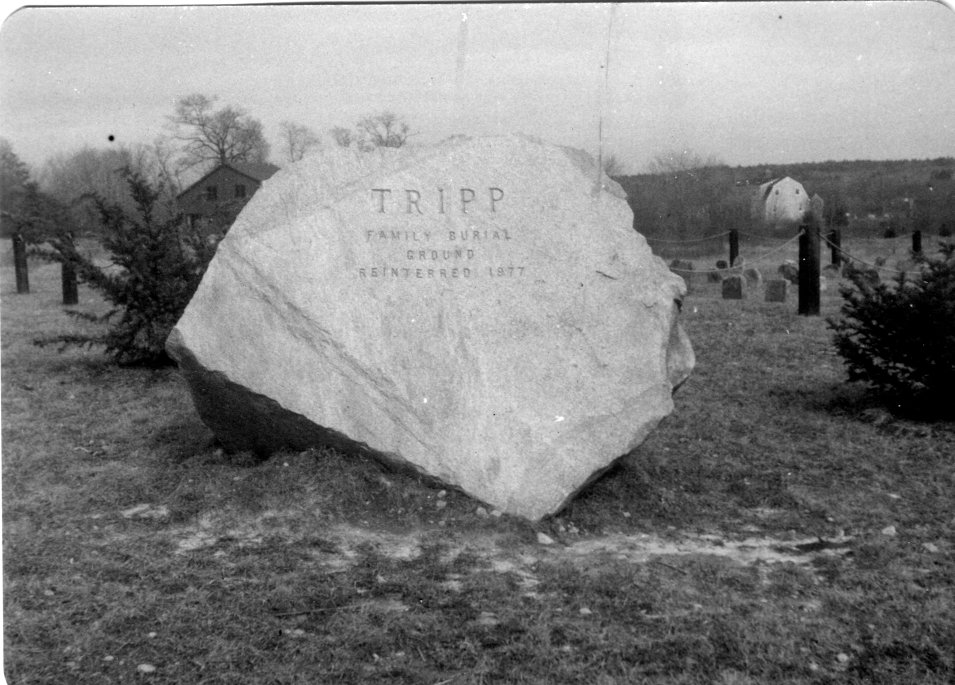

Before digging began, the location of all the markers was measured and documented and subsequently returned to their original sites after the work was completed. The property was landscaped and a large boulder with the notation “Tripp Family Burial Ground Reinterred 1977” was placed at the site.

This spring, the Westport Gravestone Cleaning and Restoration Group began restoration work at the site.

Who is buried here?

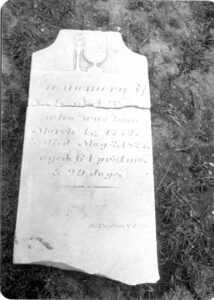

As was the custom among Quaker families into the early 1800’s nearly all the graves were marked with simple fieldstones. A number of them, however, were hand-chiseled with the initials of the deceased, year of death, and, in some cases, their age. The oldest surviving marker is that of Ebenezer himself, inscribed E x T 1791. The practice of marking graves with fieldstones gradually fell out of favor and, by 1850, had all but been abandoned in favor of marble tablets.

Six members of the family were interred under professionally-carved marble markers. They were Susannah Tripp (1791-1804), Potter Tripp (1802-1816), Otis Tripp (1792-1861) and his wife, Cynthia (Hart) Tripp (1788-1838), and Nathaniel Tripp (1773-1837) and his wife, Sophia (Davenport) Tripp (1770-1842).

Nathaniel Tripp and Lot R. Tripp were the two oldest children of Ebenezer (II)’s son, Ebenezer Tripp (III) (1749-1838), and the former Susanna Potter. Nathaniel and Lot had four younger siblings, Durfee, Restcome, Hannah and Alice, born between 1781 and 1792. Interestingly, when Ebenezer (III) died in 1838, he left each of his living children one dollar, except for his daughter, Hannah, who inherited his entire estate.

On December 18, 1791, Lot Tripp married Rachael Davenport, the 25-year-old daughter of Ephraim and Keziah Davenport, originally from Tiverton, Rhode Island. Two-and-a-half years later, Nathaniel married Rachael’s younger sister, Sophia Davenport. Nathaniel and Sophia had 10 children born between the years 1794 and 1814: Permilia (Gifford), Susannah, David, Alvin, Nathaniel, Melintha (Brown), Frederick, Julia Ann (Lawton), Eliphalet, and Sophia. Susannah Tripp (1796-1804) died at the age of 8 years. Hers is the oldest of the marble gravestones in the cemetery.

Nathaniel’s older brother, Lot, and his wife, Rachael, had 10 children of their own. Their fourth child- and fourth son- was named Potter Tripp. He died in 1816 at the age of 14 and he became the second member of the family to have an inscribed marble gravestone and was interred near his cousin, Susannah.

Nathaniel Tripp died at the age of 64 in 1837 and was interred in the family burying ground. His wife, Sophia, succumbed to congestive heart failure in 1843, a month before her 73rd birthday. Both were given marble gravestones.

Restoring the headstone for Otis Tripp, 2023.

Their eldest son, Otis Tripp, a farmer who was born on March 5, 1792, also rests here. Otis married Cynthia Hart, the daughter of John and Ruth (Rounds) Hart. This union produced five children. Cynthia died at age 50 in 1838 and was laid to rest in the family graveyard. Otis Tripp died suddenly on April 9, 1861 at age 69. A marble gravestone was purchased for Otis for $15. Noted and recorded by historian Eleanor Tripp in 1979, Otis’ gravestone has since gone missing. The last recorded burials at the site are on fieldstones, one carved B T 1871 AG 198, and J B T 1881 age 98.

Records indicate that some of those buried under the many fieldstone markers include John A. Tripp, the son of Captain Tillinghast Tripp, who died at the age of 4 months in 1808, and the captain’s grandson, Tillinghast Weston Tripp, who was 2 years old when he died in 1844. Captain Tripp’s brother, Luthan, also a master mariner, buried his wife, Lydia, here in September of 1843 at age 68.

Brownell Handy Cemetery, 138 Adamsville Road, Westport MA (Research by Richard Gifford, Robin Winters and Jenny O’Neill)

This cemetery is located a short distance from the ca1700 Stokes Potter house, perhaps the oldest existing house in Westport. The property has passed through ownership of the Potters, Tripps, Brownells and Palmers. During the 20th century this was home to Oscar Palmer and his companion Eleanor Simmons. Today the property is home to Nigerian goats and Norm Anderson and Laurie Marinone. The cemetery represents families connected by marriage: the Brownells and Handys, and the Kirby and Milk families. The 70 marked graves include two Revolutionary War veterans and two War of 1812 veterans.

Doctor Ely Handy (1763-1812) and Mary Brownell Handy ( –died 1867)

Doctor Ely Handy owned the Cadman-White-Handy House (202 Hix Bridge Road and currently operated by the Westport Historical Society). He was the physician for many Westporters during the early 1800s. Although born in Rochester, Massachusetts, he married a Westporter, Mary Brownell, whose family owned the property on which this cemetery is located. Ely Handy died at the age of 49 but his wife, Mary, lived a significantly longer life, dying at the age of 95 years in 1867. His concern for the long-term care of his wife is evident in his will which stipulated the following provisions for his wife:

- one hundred dollars

- my chaise and harness and a horse to be provided and tackled in her chaise

- one half of my household goods and indoor moveables

- the use of a sufficiency of houseroom, and a comfortable support and maintenance with every necessary of life, both in health and sickness

Ely and Mary had four children, also buried in this cemetery: Polly, James, Hannah and Mira Ellet.

Doctor James Handy (1792-1868)

Dr. James Handy was a respected and compassionate country doctor known for treating many patients for free. From his account books which chronicle the treatment of many Westport residents, we know that he charged:

“$3.00 to deliver a baby, $2.00 to mend a broken leg, 18 cents to pull a tooth.”

Early 19th-century medicine did little to cure disease. Instead, drugs such as opium simply masked symptoms. Many of the drugs prescribed by Dr. Handy induced sweating, vomiting, and bleeding in an attempt to cleanse the body.

Unfortunately, James Handy was a poor businessman. It is said that he “never paid any bills and he never collected any bills.” Following his father’s death, James was left with the responsibility to care for his elderly mother and for his sisters “so long as they shall remain unmarried.” Perhaps in an effort to create additional space to accommodate the family, James built an addition at the Handy House, borrowing a large amount of money to complete the project. Sadly, the cost of this addition combined with his reluctance to repay the loan eventually brought financial ruin to his family.

Nathan Crary Brownell (1787-1861) and Hannah Borden Wilbour (1793-1839)

Nathan Crary Brownell grew up on this farm and as an adult had substantial business interests in New Bedford. In 1845 he purchased the Stone House at the Head of Westport. In 1810 Nathan married Hannah Borden Wilbour of Little Compton. Hannah’s father, Gov. Isaac Wilbour, was a man of great prominence in Rhode Island politics. Hannah’s sister was a suffragette and abolitionist acquainted with Susan Brownell Anthony and Frederick Douglass. Nathan & Hannah’s son Abner Crary Brownell (1813-1878) was a wholesaler in the Midwest and served two terms as Mayor of Cleveland, OH. Nathan & Hannah’s grandson William Crary Brownell became one of the nation’s leading literary and art critics.

Stephen P. Kirby (1815-1902) and Harriet Newell Brownell (1819-1857)

Stephen P. Kirby, whose ancestors had lived in Westport since the 1680s, was a prosperous cattle dealer. The practice in those days was for cattle drovers to bring their herds up and down local roads, stopping in front of each farm. The farmer would sell cattle to the dealer, usually milk cows who were past their prime, and sometimes in return buying a young calf whose productive life was still ahead, much in the same manner as we might trade in a used car to a dealer in exchange for a new car, with cash as boot to even up the trade. Kirby would then drive the herd overland to Brockton, where they would be sold to a slaughterhouse. Stephen & Harriet’s son Albert C. Kirby purchased the Stone House, and their Kirby descendants lived there until recent times.

Hannah Handy (1797-1892)

Hannah, the unmarried sister of James Handy, was probably born in the Handy House and lived there her entire life. Hannah never married or had children, instead she was surrounded by various generations of close family and acquaintances throughout her lifetime. These included her parents, brother, nieces and nephews, and various other individuals who lived and worked on the farm over the years. The financial dealings of her brother led to bankruptcy and the loss of the Handy House, her home. Yet the story does not end there! Through the kindness of friends and family, and through her hard work as a seamstress, Hannah Handy then aged 79, regained possession of the house. It was to remain in the Handy family until 1911. Hannah Handy died on December 31, 1892. She was 95 years old. The cause of death was simply identified as “Old Age.”

Frederick Brownell (1789-1872) and Charlotte A. Sisson (1792-1832)

Frederick ran a general store and post office at the west end of Hix Bridge. In 1814 he entered into a plan with his cousin Dr. James Handy to purchase Hix Bridge and adjoining land for $4000. Under this arrangement the deed would be filed in Dr. Handy’s name, Brownell would pay Handy $1400 immediately and the remaining $700 due Handy would be “taken out of the store.” In exchange Dr. Handy would convey to Brownell the bridge, the store and toll house, and 6 acres, with Dr. Handy retaining title to the remaining 50 acres (located across from the Handy House on the south side of Hixbridge Road). Dr. Handy ran up large bills at the store, crossed the bridge toll-free, and incurred other expenses paid for by Brownell to the total of $3,648, far in excess of the $700 agreed to as the remaining compensation. Despite repeated demands from Brownell, Dr. Handy never delivered a deed, telling him that he would get around to it in due time. In the 1870s the town of Westport purchased the bridge, in order to remove the tolls, and the estate of Dr. Handy claimed to be the owner, but after lengthy court proceedings, Brownell was determined to be the owner despite not having a deed.

Fallee Brownell (1790-1881)

An unmarried daughter of Abner & Hannah (Crary) Brownell, Fallee became a cook and housekeeper for Sylvia Grinnell Howland of New Bedford, heiress to the Howland whaling fortune.

Sylvia entrusted Fallee with the keys to her hair trunk, located in a closet and containing her financial papers. Sylvia’s relationship with Fallee earned the lifelong resentment of another member of the household, Sylvia’s niece Hetty Howland Robinson, later to become famous as Hetty Green, “The Witch of Wall Street.” In one episode, Hetty threw the elderly Fallee down a flight of stairs, resenting Fallee’s continued refusal to give Hetty access to her aunt’s trunk. Hetty nonetheless managed to forge a version of her aunt’s will more favorable to Hetty, which was thrown out by the courts. On her deathbed Sylvia told Fallee that she had provided for her in her will (a $3000 bequest) sufficient for Fallee to live on her own, as she was afraid that after her death “Hetty will never be as good to you as I’ve been,” a point on which Fallee needed little convincing.

The 1872 will of Fallee Brownell specified that her body was to be interred in the “Brownell burying ground” and that “suitable grave stones like that of my sister Dorothy should be erected on or near the spot where my body is interred.” The will further provided that the southwest corner of the burying ground should be cleared of bushes and their roots “so as to exterminate them within at least one square rod,” and that “suitable graves stones be erected for my Father’s and Mother’s graves, at a cost not exceeding sixty dollars for both graves.”

Edward B. Kirby (1847-1862)

Edward B. Kirby was the son of Stephen Kirby and Harriet Newell Brownell Kirby and was born on September 2, 1847. At age 14 he signed on as crew for a whaling voyage on the bark “John Dawson” out of New Bedford. It was his first and only voyage.

The “John Dawson” departed on May 10, 1862 and returned in 1864 but without Edward. While cruising the whaling grounds off River La Platt, South America, sperm whales were sighted off the bow. The whale boats were lowered in chase and were “stove” by the whales. All of the crew were rescued except for Edward. The logbook entry for that day has vertical whales stamped on the page which signifies whales that got away. There is also a single coffin.

It must have been very difficult for Captain Cornell to tell Edward’s father Stephen Kirby of Edward’s tragic death. Edward had celebrated his 15th birthday during the voyage and had died just before Christmas. His 5 year old brother Henry Philip Kirby had died of scarlet fever just a couple of months before Edward left on his ill-fated voyage, and Edward’s mother Harriet had died 5 years prior in 1857 at only 37 years old.

Abner Brownell (1756-1851)

On April 20,1775 Abner received word that the British were causing trouble in Boston and war had begun. He saddled his horse and galloped through Westport, calling out all the minute men in town. Within a few hours a company were on their way to Boston. Today he is remembered as Westport’s Paul Revere

GIFFORD – RICHMOND – MOSHER BURIAL GROUND

29 Reed Road, Westport MA

Research by Todd Baptista

The original land owner of this property has not been determined, although it is likely owned by John Gifford or his in-laws, the Milks, who also owned land and built homes in the Head of Westport in the early 1800s. The first burials in this cemetery were marked by fieldstones. The earliest dated stone, 1821, is from the Richmond family. Several of Richmond family infants are known to have been buried here between 1813 and 1820.

THOMAS RICHMOND, MD

The first physician to serve the Head of Westport was Dr. Thomas Richmond. Born in Dighton in 1779, he completed training at Harvard College. Described as tall, dark and distinguished, he married Mary Shearman, of Swanzey, daughter of the illustrious Peleg Shearman/Sherman (1747-1811) a colonel of the First Regiment of Infantry. The Richmonds had eight children. Their first three died in infancy and were buried in this cemetery.

As his practice grew, Dr. Richmond built a home and office at 21 Drift Road, just north of the Bell School. The family welcomed a new baby into the home with the birth of Charles W. Richmond, named for Thomas’ younger brother, in January of 1818. A daughter, Mary Jane, was born in 1820. Sadly, Charles died of an illness at the age of 3. The boy was interred alongside his siblings atop the hill and, for the first time, the gravesite was marked with an inscribed marble tablet.

His eldest daughter, Sophia, died on April 10, 1840 at the age of 17, most likely from tuberculosis, and was also interred there.

Dr. Richmond’s probate inventory provides a fascinating glimpse into the life and finances of the simple country doctor. He owned a sulky — a lightweight cart with two wheels and a seat– a horse, and a sleigh, which he would use when making house calls. A hog and burro and a multitude of farming implements including a shovel, assorted hoes, a winch, wheelbarrow, manure fork, rake, rat trap, and flour barrels were also inventoried. The graves of the doctor and his wife were marked, not with an elaborate monument, but simple square-top marble tablets. Thomas’ inscription includes the M.D. designation, memorializing the first physician to live among, and care for, the residents at the Head of Westport 200 years ago.

JOHN GIFFORD

Mayflower descendant John Gifford was born in Westport in 1754. His father, Recompense Gifford (1732-1826) was a native of Tiverton and had married Susanna Taber (1732-1803). He served in the Colonial Army during the Revolutionary War, representing the Town of Dartmouth. By 1776, he had risen from the rank of Private to Sergeant. In 1778, after completing his military service, he married Isabel Milk (1753-1846). The couple had 12 children, six sons and six daughters. Sylvia, Peace, Nancy, Patience, Amy, Zaccheus, Rebecca, David, Alden, Squire, Nicholas, and John. Residing near the Head of Westport, John Gifford lived to the respectable age of 77, dying on November 9, 1831.

FREDERICK and MARY MOSHER

Frederick Plummer Mosher was born February 9, 1822 in Dartmouth to Richard Mosher and the former Cynthia Rogers. In his youth, he made his living on the sea as a mariner. He married Mary M. Gifford, the daughter of Zaccheus and Waity Gifford of Dartmouth. The couple had two sons Albert and Frederick E., and two daughters Cynthia Ann and Adaline. As the family grew, Fred gave up his life on the sea for a life of farming. He joined the Noquochoke Lodge of the Masons. Mary died of “old age”, at the age of 78 and was buried alongside her parents in this cemetery. Fred was buried alongside her. It is interesting to note that the couple’s placement in their graves is opposite the standard burial arrangement of the day. When standing before the headstones, the male is typically at left and the female at right. In this instance, the coffins are reversed, allowing Mary to rest between her mother and her husband.

ZACCHEUS GIFFORD

Like his father, Zaccheus Gifford served in the Army and also fathered 12 children. Born in September of 1787, he was 19 years old when he began courting Waity Crapo. Waity had been born in Freetown and, like Zaccheus, was the child of a Revolutionary War veteran. The couple were wed in 1807. Zaccheus served two brief tours of duty during the War of 1812. He served as a Private in Captain Jonathan Davis’ company, organized in Westport, and the Massachusetts Militia under the command of Captain Reuben Swift. His service was completed on August 4, 1814.

Returning home, Zaccheus toiled as a farmer for the remainder of his life and accumulated substantial parcels of land. Zaccheus and Waity had 12 children: Frederick, Ruth, and Leonard, Lauretta, Elkhanah, Amanda Marie, Lemuel, Mary, Eveline, Caroline, Franklin, and a second Caroline. Three of their offspring died in childhood, but the other nine all lived relatively long lives.

Zaccheus died in Dartmouth on May 25, 1865 in his 78th year. The cause of death was listed as a paralytic fit, likely a seizure after suffering a stroke. His wife of nearly 58 years, Waity, outlived him by 15 years, passing in 1880. Two of the couple’s sons died soon after their father – Leonard, of pneumonia, and Frederick, a local machinist, of diabetes. Sadly, son Lemuel, a gardener, committed suicide by hanging in July of 1901 at the age of 82. The couple’s marble gravestones are large, heavy, and, by community standards, more expensive than most of the stones seen in Westport during the 19th century.

THOMPSON CEMETERY (Research by Todd Baptista and Richard Gifford)

This small family burying ground was established on land formerly owned by Isaac Howland (1763-1828). This small cemetery was restored by family descendant Sam Manley in 2017. Seven members of the Thompson family are buried here. Alvah Thompson settled in Westport as a young man, and married Lydia Chase, 10 years his junior. When their daughter, Lucy, died at the age of 15 months in 1839, she was buried here. Another daughter, Judith, was only seven days old when she died in 1850. Their son, Henry, died at 13 in 1853, and was buried alongside his sisters in this hilltop burial ground. Son, Ephraim, a farm laborer, died at age 32 in 1864. At the time, typhoid fever and tuberculosis claimed many young lives across the nation. The couple’s second daughter, Lucy, succumbed a month before her 21st birthday in 1865 and joined her siblings in the family graveyard.

By 1880, all of the Thompson children had left the family home. Their daughter, Elizabeth, married a local man named Stephen Tripp and lived close to Alvah and Lydia, who were married for a total of 55 years. Alvah died of what was termed “old age” in his 83rd year. His wife, Lydia, lived another seven years, dying of osteosarcoma, or bone cancer, in 1890, at age 79. The couple were buried alongside the five offspring who had been interred in this small cemetery.

GIFFORD-WHITE-CORNELL CEMETERY

Hix Bridge Road, Westport MA

Research by Richard Gifford

This cemetery is located on one of the earliest farms to be established in Westport, owned by Samuel Cornell in 1669. His land stretched from the East Branch easterly almost to Division Road. Samuel’s father Thomas Cornell emigrated from Saffron Walden, England to Boston by the 1630s. Referred to in records as an innkeeper and a “maltster,” Thomas was brewing beer in Boston more than a century before Sam Adams.

Thomas was a follower of Ann Hutchinson and followed her to Portsmouth RI and then to New Amsterdam. At least one of Thomas Cornell’s children were killed in the 1643 Indian massacre which took the lives of Hutchinson and sixteen of her followers, at which point the Cornell family returned to Portsmouth, where Samuel was likely born in 1644.

Samuel’s son Thomas Cornell (1685-1763) continued to live on the farm and married Catherine Potter, another early Westport family.

Thomas’ son Peleg Cornell (1719-ca1782) was the next generation to live on the farm. He married Mary Russell. Her great-grandfather John Russell was residing in Dartmouth by 1662, when a Native American with five others (including Suquatamake, a landowner in Acoaxet) accused him of providing a “pretended cure” for his illness in exchange for the Indian’s gun.” Russell “took up an axe, and endeavored to improve it against the said Indians in a turbulent and dangerous manner.” The end result was that the Indians were fined and Russell got off with a warning.

The farm was purchased at auction by Andrew Sherman Macomber (great-grandfather of “Cukie” Macomber) and in the late 1800s was purchased by the Smith family, immigrants from Scotland who mainly grew potatoes on the land.

16 marked stones, 3 unmarked stones

Abraham Cornell (1744-1826). A great-grandson of Samuel Cornell, Abraham likely occupied the home built by his great-grandfather, located on the north side of the road in the vicinity of 408 Hix Bridge Road. His wife Priscilla Sanford, as noted below, was a great-great granddaughter of Ann Hutchinson. Their only surviving child and heir was Cynthia Cornell, who married William White, a great-grandson of the William White who built the east end of the Handy House. Following William White’s death the farm was owned jointly by his 13 children

Priscilla (Sanford) Cornell (1745-1824) Born in Tiverton, Priscilla was a great-granddaughter of Ann Hutchinson, who was expelled from Boston and was one of 19 signers of the Portsmouth Compact in 1638. Priscilla’s great-grandfather, John Sanford served as President (governor) of Rhode Island in 1653, and married Bridget Hutchinson, a survivor of the 1642 massacre which took the life of her Ann Hutchinson, her mother. Bridget did not escape being publicly whipped in Boston for attending Quaker meetings.

William White (1773-1842) A great-grandson of the William White who built the east end of the Handy House, who in turn was a great-grandson of Peregrine White, born on the Mayflower when anchored off Provincetown. William was also descended from the Mayflower passenger Francis Cooke, John Cooke and Richard Warren through his great-grandmother, Elizabeth (Cadman) White. The younger William White, a hatter, was a prominent man in Westport political circles. Early town meetings were sometimes held at his house. .

Cynthia (Cornell) White (1778-1862) Only surviving child and sole heir of Abraham & Priscilla Cornell, married William White, a great-grandson of the William White who built the east end of the Handy House. Following William White’s death the farm was owned jointly by his 13 children. In addition to this sprawling homestead farm, Cynthia inherited the land at the Head of Westport where the Stone House and Bell School now sit, which she sold to her son William White. After Cynthia’s death, the remainder of this farm was put up for auction in 1865, with the following description:

The 150 acre homestead farm of the late William White, Esq. is well supplied with never failing water, constantly running and never freezing. It joins the river below and near Hix’s Bridge, extending along the shore for over a mile, thus affording very great facilities for obtaining seaweed. The soil is well-adopted to grain of all kinds, excellent grass land, easy of cultivation and to an enterprising man in the few years will make as valuable a farm as this section of the country affords. To anyone wishing for a farm it is well worth consideration as an opportunity that is rarely presented.

Leonard Gifford (1792-1843) A great-grandson of Robert Gifford, who (with brother Christopher) relocated to Old Dartmouth from Sandwich in the mid-1680s. Along with other Quaker families like the Allens, Wings and Kirbys, the Giffords likely settled in this area, at least in part, to escape the persecution they had endured in Sandwich. The infant Peckham child buried here was a grandchild of Leonard.

Jonee Soule (1790-1861) A tailoress, Jonee was the fourth great-granddaughter of Mayflower passenger George Soule. Her third great-grandfather, Nathaniel Soule, was one of a small handful of settlers who (like Samuel Cornell) were living in Old Dartmouth before King Philip’s War. In 1674 Nathaniel Soule was charged with fathering a child by an unnamed Indian woman, and ordered to pay 10 bushels of corn to her for the child’s upkeep. Jonee was the daughter of David & Peace (Sherman) Soule, and she would have grown up in the ca1790 house at 1415 Drift Road. Her neighbor across the road was Capt. Paul Cuffe. In 1850 Jonee was living with the family of her nephew, David Sowle Howland, a carpenter. In the same year she purchased the property at 426 Hixbridge Road.

Rev. Philip Sanford Jr. (1787-1869) Born in Tiverton, Philip was a distant cousin of Priscilla (Sanford) Cornell, and a distant cousin of his second wife Cynthia (Gifford) Howland. By his first wife, Phebe Ann Castino, he had several children. His first wife’s father, Raimon Castino, was by tradition a French soldier occupying Newport in the later years of the American Revolution under the Comte de Rochambeau who went AWOL and moved to Westport. Philip Sanford’s family was living in Canandaigua, Ontario Co. NY in the 1850 census, where he was a farmer. Returning to this area, Sanford married Cynthia (Gifford) Howland.

FRIENDS NORTH BURYING GROUND

19 Main Road, Westport MA

Research by Todd Baptista, Richard Gifford and Robin Winters

Although we know it as Friends North now — to delineate from the other site in Central Village — originally this was known as the Friends’ Center Meeting House. The Society of Friends, also known as Friends Church or Quakers, is a Christian group that arose in mid-17th-century England, dedicated to living under the “Inward Light,” without creeds, clergy, or other ecclesiastical forms. Quakers were also known to refuse to participate in war, wore plain dress, opposed slavery, and abstained from alcohol.

At one time, the Friends North Meeting House stood at the front of this site with the cemetery directly behind it. Around 1850, the Meetinghouse was moved to the east along Old County Road to the site of the current new Westport Junior-Senior High School. 174 Quakers were buried here, mostly with unmarked fieldstones documenting their placement. The oldest known burial on the property is a member of the Howland family, dated 1799. The Quakers believed it inappropriate to elevate one’s status above another in life and in death, and that gravestones would serve to distinguish some individuals from their neighbors and peers. Around 1850, the practice changed, and simple, small gravestones with name, date of death, and age were allowed, but without any decorations or epitaphs.

Many of the men and women who worked and lived at the Head of Westport in the early 1800s are buried here.

ADAM AND ABNER GIFFORD

Members of the Gifford family were active in town politics and in mercantile activities here from about 1802-1857. Adam Gifford farmed, owned and operated a general store, sold goods at public auction, and also served as a selectman for the town from about 1815-1821. He was also noted to be the first sheriff at the Head of Westport.

His brother, Abner B. Gifford, born in 1784, was also a local merchant. He served as a justice of the peace for Bristol County and as a trial justice, transacted much of the local probate business, and was a member of the “Prudential Committee” for School District No. 19 in Westport, as well as owning partial interest in several whaling vessels. Abner died in 1847 of dysentery.

ISRAEL & NANCY CHACE

Both of these gravestones, small rounded top marble tablets, plain and very much in the style of the Quaker gravestones of the mid-1800s, were discovered broken in 2022 under the large tree that once stood here. Israel Chace was born in Swansea in 1800. He learned the trade of construction carpenter, moved to Westport, and married a 15-year-old bride, Nancy Gibbs Mosher on October 23, 1827. The couple had eight children including a son, Charles (1832-1907), who married four times and committed suicide by ingesting arsenic at age 75 after a being ill and bedridden for an extended period of time.

Despite the considerable difference in their ages, Nancy was the first to die after 34 years of marriage. She was 59 when heart disease claimed her life on December 13, 1861. She is buried here near the bodies of her children, Emily and William.

EMILY CHACE

When the process of removing the giant Norway Spruce tree from the center of the Friends North Cemetery commenced last month, we were surprised to find the previously undocumented gravestone of Emily Chace, buried under several inches of mulched pine needles and soil at its base. Amidst the trash and other debris that had been left at the site, it was surprising that this stone existed in one piece. Perhaps being buried saved it from further damage of foot traffic. Emily was the tenth and last child born to Israel and his wife Nancy in 1851. She died tragically, at the age of 2 years, choked to death when a bean she was eating became lodged in her windpipe. Her family buried her beside the brother she never knew, almost directly under the site that the iconic tree would occupy.

JOHN A. GIFFORD

John Allen Gifford was born in Dartmouth in 1785. He married 22-year-old Mercy Slade in 1813. In their 24 years of married life, the Giffords had at least seven children. A son, Edward Slade Gifford purchased the old Rotch Forge, Westport Manufacturing Mill #2, and converted it into a hoe factory in the 1840s. When gold was discovered in California, Edward got gold fever and went there in the hope of striking it rich. He died there in 1851.

The Giffords lived at the southwest corner of Reed and Forge Roads. John’s brother, Anthony, owned the rule factory upstream from the forge on the east bank of the river, which made carpenter’s rulers. By the 1850s, they employed a total of 17 men. John A. Gifford Jr. honored the memory of his parents and young brother Caleb by having matching marble gravestones with granite foundations carved and installed at this burying ground.

HUMPHREY DANIEL HOWLAND

This recently discovered gravestone marks the burial site of Humphrey Howland, born in 1812. His small square-top gravestone was one of the first professionally carved gravestones to be placed at Friends North. Several fieldstone markers with rough cut initials suggest that the row Humphrey occupies is filled with other members of the Howland family dating back to 1799. Interestingly, the dark gray stone used for both Humphrey and Rhode Howland’s markers are not slate, but a type of stone known as schist. These two stones are the only schists we have identified in Westport’s cemeteries.

Humphrey was the son of Daniel Howland and the former Rhoda Hathaway. Daniel had built a Cape-style home for his family which still stands today at 3 Drift Road at the Head of Westport and operated a store from his basement. Humphrey was named for his paternal grandfather, Humphrey Howland, a devout Quaker merchant with substantial money. The senior Humphrey Howland had built his home in 1775 at 790 Gifford Road, a structure which also still stands. The family attended services at the Friends North Meetinghouse.

At 21, Humphrey D. Howland declared his intention to marry Rhoda Allen on the 27th of January 1836. The couple were married on February 21, 1836, but their marriage was sadly a short one. Still a newlywed, Humphrey D. Howland died on December 8, 1836, aged 24. The cause of death was not recorded, although tuberculosis and pneumonia are likely causes. Had Humphrey survived, he would likely have inherited the famed Stone House, the Job Milk Farm, and nearly 200 acres of land from the present site of the Westport Fairgrounds across the East branch of the River to Drift Road. Humphrey’s mother is buried alongside her only son, her grave marked with an identical stone to his own.

PARDON AND PEACE GIFFORD

Within the last few years, all but one of the Gifford family stones have been broken into pieces. Pardon Gifford was a shipwright, a skilled carpenter who constructed and repaired whaling ships in the early and mid-1800s. He was also a part owner in at least one three-masted vessel, the Herald, a New Bedford-based whaler. Through his efforts, he acquired a considerable fortune, including a home in New Bedford. In his Will, Pardon stipulated that his wife would inherit the family home, furniture, livestock, farming tools, carriages, harnesses and hay. He also bequeathed a tidy sum of $2,000 to her. He requested that any other real estate he owned was to be auctioned, and that any investments or holdings he had in ships should be divested and re-invested in railroads, banks or other stocks that could provide an annual dividend or income. Peace Gifford, 67, died of heart disease just six days after her husband of 50 years. The couple were buried side by side, near the burial spot of their son, Robert.

ABNER AND NANCY THOMSON

Nancy H. Thomson (Nancy Howland Gifford Thomson) was the daughter of Pardon Gifford and Peace Howland. She was born March 7, 1805 and married Abner Thomson of Dartmouth on December 1, 1822. Abner and Nancy lived near the Head of Westport in a large two story dwelling house with outbuildings. There was a Saw Mill, a Grist Mill with two runs of stones, a Fulling Mill, and a Carding Machine on the property. It was considered to be one of the best in this part of the country for a cotton or woolen manufactory according to the ad placed in the newspaper. According to local historian Curtis Pierce, ‘this machinery, the first of its kind in the stream was cast in Isaac Macomber’s foundry which was across the stream below the Grist Mill.”

PHEBE BAKER

Phebe was the daughter of Charles Baker and Sarah Weaver. She was born in Westport on the “19th day of the 7th month” of 1796 and died on the “14th day of the 6th month” in 1820, just shy of her 24th birthday. She lived with her parents and siblings at what is now 596 Old County Road. Her father Charles built the house around 1782 when he was 18 years old and he had a tannery in the back. Charles and his wife Sarah had a written marriage contract when they married in 1791.

In 1807, young Phebe stitched a needlework sampler which is now in the collection of the Westport Historical Society. The sampler has a variety of stitches with three styles of alphabets, an anchor, and a strawberry border. There is also a house with two long doors which may depict the Centre Meeting House. There are no known photos of the meeting house, but the two doors could represent the separate entrances for men and women at Quaker Meeting Houses. The verse reads “Let the sweet work of prayer and praise employ our youngest breath. Thus we are prepared for longer days or fit for early death.”

ABRAHAM AND MARY MACOMBER

The twin rounded-top marble stones of Abraham and Mary Macomber were broken off their marble base many years ago, either by vandals or an errant branch from the old tree and repaired in 2022.

Born into the Society of Friends, Abraham and Mary Macomber were among the very last individuals to be interred here. Abraham was skilled as a blacksmith, and practiced the trade during what is referred to as the “Golden Age of American Blacksmithing”, the mid-1800s, due to the high demand for metalwork. In 1860, blacksmithing was the fourth most popular trade in the United States. He operated his own shop near the Head of Westport. At birth, Abraham was given the middle name Eben, a shortened version of Ebenezer, of Hebrew origin, meaning stone, or rock.

Abraham died of what was termed “old age” in 1891 at age 86. After her husband’s death, Mary moved in with her widowed daughter, Mary Ellen Almy, and enjoyed the company of her three surviving children, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. She remained very active doing church work well into her 80s, and also excelled doing needle work. Mary Macomber became the final soul to be buried at Friends North, 103 years after its initial use.

REBECCA AND LYDIA C. EARLE

Rebecca Earle, was 19 years old and apparently unmarried when she fell pregnant in late 1810. She gave birth to her daughter, Lydia, in Tiverton, RI on August 28, 1811. Both Lydia’s birth and death records do not include a name for her father and neither appear to have ever been married.

Mother and daughter lived together throughout their adult lives, occasionally sharing their residence with boarders. Rebecca died on February 18, 1871 at age 78 Lydia was a housekeeper, although we don’t know if she worked for other families or if the position was caring for her own boardinghouse. She died of chronic kidney disease on January 10, 1893 at age 81. She is buried near her mother

Charlotte White Cemetery

Oak Ridge Lane, Westport MA

The stories represented by this small cemetery are complex:

- The survival and resistance of Native Americans in the face of settlement by Europeans, disease, war, and loss of homelands and culture.

- New partnerships and kinship networks reshaped and strengthened by marriages between Native Americans and enslaved African Americans.

- The presence of slaves in Westport and the relationships between the enslaved and the individual slave owners.

Charlotte White’s family represents all strands of this story. She is identified as an “Indian doctor” in the census of 1861. Her mother was Native American and her father was a former slave. The cemetery stands on property owned by Charlotte White’s father and mother.

Charlotte White (1774-1861)

Charlotte White is an intriguing character from 19th century Westport, with connections to Native American and African American history, slavery, poor relief, folk medicine, and midwifery.

A newspaper article from 1839 describes Charlotte White as “the great king’s evil and scrofulous humor doctress.” Scrofula was a tuberculous swelling of the lymph glands. She took in and treated poor or troubled people, before the almshouse was established, and was reimbursed by the town. In 1816 Charlotte was reimbursed for keeping Henry Pero, a black child, two weeks and two days old, and also received $2.86 for making clothes for him. In a remarkable entry in the town records for 1818, she was paid for “keeping Nursing and doctoring” Deborah Pero for 14 weeks. The use of the term “doctoring” in the official records gives credence to her reputation as a healer.

Charlotte was connected to Westport’s well-known mariner, philanthropist, and black rights advocate Paul Cuffe (1759-1817). They both had a Wampanoag mother and an African father who had been a slave. Charlotte’s sister Jane married John Cuffe, Paul’s brother. There are also numerous links between Charlotte and the Wainer family, who were in-laws and business partners of Paul Cuffe.

It appears that Charlotte did not marry; she is listed in one census as a “colored maiden.” Charlotte died on June 17, 1861, at the age of 87, of “lung fever” (probably pneumonia).

Charlotte, Charlotty or Charlotta?

How is her name pronounced? Charlotte’s name was not pronounced then as we would pronounce it now. Town records show that it was listed phonetically as “Charlotty.” A second clue can be found in the town records regarding early poor relief in Westport referring to her as “Cholata” White. Based on this evidence, it is most likely she was called “Sha-lot-ah.”

Elizabeth (David) White (1730-1827)

Charlotte’s mother, Elizabeth (David) White, was a Native American from Tiverton. Elizabeth was perhaps the granddaughter of Job David, one of the original settlers of Watuppa Reservation.

Zip White

The presence of slaves in Westport is documented in probate records and town records. Charlotte’s father, Zip, had been enslaved by George White, one of the original owners of the Handy House on Hix bridge Road. Zip White is sometimes referred to as “Sip” in records, which is perhaps a shortening of Scipio, a name sometimes assigned to slaves, as were other “Roman” names (Ceasar, Augustus, Pompey). Elizabeth and Zip married in 1765, while he was still a slave. In addition to Charlotte, they had a daughter Jane and two sons, Joseph and Job. Under the 1764 will of George White, his slave Zip was to be given his freedom on March 25, 1766, and at that time to be given a ten-acre parcel of land on which this cemetery stands. It is not known if Zip is buried on this site.

Further information: Who was Charlotte White?

ALLEN-WILCOX CEMETERY

One Hav a look Lane , Westport MA

Research by Richard Gifford

34 marked stones, 26 unmarked. Individuals with inscribed stones marked in bold.

Perhaps the most picturesque setting for any burial ground in Westport, the Allen-Wilcox Cemetery overlooks the East Branch. This area of Pine Hill Road was settled by Daniel Wilcox (1623-1702) who acquired extensive lands throughout Old Dartmouth, including all of Westport Point. Wilcox had a reputation for living “among the Indians” and he became fluent in the Wampanoag language, serving as an interpreter for Col. Benjamin Church during the course of King Philip’s War. Shortly after the war, Wilcox was deeded 200 acres by the Acoaxet sachem Mamanuah.

Daniel’s son Stephen Wilcox (ca1668-1736) was a Quaker of high status. Stephen likely built the Westport Town Farm on Drift Road, where he lived (this did not become town property until a century later). His son Stephen Wilcox Jr. (1709-ca1753) built the ca1730 house across the road from this cemetery at 722 Pine Hill Road. Unlike his father, Stephen Jr had numerous disputes with the Dartmouth Friends. At one point the meeting appointed a committee to take charge of Stephen Jr.’s finances, when he apparently faced some difficulties with creditors. Stephen objected to the Friends’ intervention, and . . .appeared in this Meeting in a very passionate manner, casting heavy Reflections on us, saying we should have fewer Testimonies [condemnations], saying he believed that it was a pity we should have any except some to reprimand us for our Wickedness, and

stamping his feet on the floor in a passionate manner, to the great grief and sorrow of the sincere at heart…

Naturally the Quaker elders did not take kindly to such criticism, and finding in Wilcox the “prevalence of the Adversary” [i.e. Satan] they promptly disowned him.

Abner Wilcox (1742-1816) Stephen Jr.’s son lived in the ca1750 house located south of the burial ground at 757 Pine Hill Road. Abner’s is the oldest of the inscribed gravestones at the Allen-Wilcox Cemetery. This house later was occupied by his son Abner Wilcox Jr (1783-1867). Census records show that this house was shared with Abner Jr.’s son-in-law Deacon John Allen (1809-1900). A filing in the land records notes the purchase of a pew at the Second Methodist Church of New Bedford by Deacon John Allen, and it is most likely that his association as a deacon was with that church.

Elizabeth Chace (1792-1865), the wife of Abner Wilcox Jr., introduces another prominent family to this neighborhood. Her father Peleg Chase came to Westport from Somerset and in 1806 purchased a farm centered on the house at 722 Pine Hill. The farm was sold to his son Philip T. Chase (1801-1859), who had married Ruth Wilcox (1798-1866). Their son William Wilcox Chace (1826-1908) occupied the farm for the remainder of the 19th century.

Job Allen (1782-1832) built the house at 699 Pine Hill, just north of the burial ground. The Allens were among the earliest settlers (and largest landowners) of Old Dartmouth, with four brothers (Joseph, Increase, Ebenezer and William) moving from Sandwich in the 1680s, likely motivated — like their Sandwich neighbors the Kirbys, Giffords and Wings — by a desire to escape the persecution of Quakers taking place there.

James Allen (1820-1896). James lived here for most of the 19th century and there is evidence of a blacksmith shop on the property, which perhaps James operated.

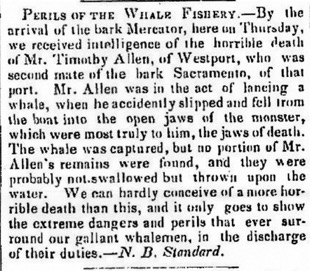

Timothy C. Allen (1821-1853). A whaler, Timothy is recorded in Westport Vital Records as “killed by a whale” on August 2, 1852. Just over a month later, his son Capt. Timothy Chace Allen (1853-1923) was born. Just two weeks later the young mother, Abbie W. Chace (1833-1852) died of “bilious fever,” Abbie being the daughter of Philip T. & Ruth (Wilcox) Chace. The young orphan was raised in the household of his uncle, Deacon John Allen. Given his title of captain, one would be tempted to surmise that he resolved to become a whaler himself In order to hunt down, Captain Ahab-style, the perpetrator of his father’s demise, but the truth is he hunted perpetrators of a different sort: his title as captain was derived from his rank in the New Bedford Police Department, where he lived as an adult.

Friends Central Cemetery

The Friends Central cemetery is the resting place for many Quakers of the last 300 years. Originally marked headstones were not used for burials, but rather crude fieldstones were placed at the burial site. The Quakers believed it inappropriate to elevate one’s status above another in life and in death, and that gravestones would serve to distinguish some individuals from their neighbors and peers. Around 1850, the practice changed, and simple, small gravestones with name, date of death, and age were allowed, but without any decorations or epitaphs. The earliest marker is 1811 for Deborah Tripp Chase. It is not clear if these stones were placed at the time of burial or later. Medallions can be found in the ground which marked burials, and probably records were kept of those burials but are now lost. Similar medallions are found in the Potters Field at Beech Grove, again with no records of who is interred.

Many of the stones in this cemetery are badly damaged, caused by either a poor quality marble or the use of bleach to try and clean the stones or perhaps both. In the 1970s it was common to use household bleach to try and kill lichen and mold growth on marble and granite gravestones. Even worse than a strong alkaline solution are acid-based household cleaners such as Borax or Fantastik.

Paul Cuffe (1759-1817) and Alice Cuffe (1756-1819)

Captain Paul Cuffe and his wife, Alice Abel Cuffe, are buried here. Captain Cuffe, a Native American African American man, lived between 1759 – 1817, a resident of Westport since he was 15. His life and heritage are extraordinary. His father, a freed slave, adopted the Quaker ways but was not part of the Quaker community. Paul Cuffe however was officially accepted by the Quakers in 1808, the first person of color in the Westport Friends Community. Cuffe served on important committees and built and helped finance the new Meeting House. Befittingly, he and his wife Alice (a Native American) are buried in the grounds to the North of the Meeting House. Their burial site is located near other graves marked by medallions. Their great- grandson, John C. Nicholson, is buried nearby. He was a coachman. His mother Catherine Cook Nicholson inherited the original Paul Cuffe homestead on Drift Road from her mother Alice Cuffe Cook. His father, Joseph Nicholson was from St. Nicholas, Azores.

John Macomber (1785-1867) and Mary Slade Macomber (1784-1861)

The Macombers were closely associated with the Westport Monthly Meeting of Friends. John Macomber was its Clerk for many years and was regarded as “a man ahead of his time” who “followed the early Friends idea of simplicity of dress and lack of color.” A granddaughter of his went up to him and said, “Grandfather, see my red stockings and new bronze shoes.” To which he replied, “I see all I want to of them.” John Macomber married Mary Slade, a Quaker from Dartmouth.

John was a “market man,” a farmer who raised vegetables to sell in the city. The purchase of their land had exhausted their funds, and according to great-granddaughter Marianna Macomber’s memoir they could not afford a clock. Needing to awake at 3:00 AM to start the journey to New Bedford, a time even before the most diligent rooster would raise an alarm, Mary stayed up all night and turned an hourglass so that she could awaken her husband at the appointed hour.

John was known for his tree nursery and for his mulberry trees, grown specifically to provide nourishment for silkworms, supporting a small-scale silk making industry. He was one of the originators of what became the Rhode Island Red breed. In their lifetimes, though, the birds were called “Macomber fowls” or, more commonly “Tripp’s Yaller [Yellow] Hens.”

Lydia Macomber Webster (1811–1892)

Lydia and her sister Olive were born deaf. Their father John Macomber was a great believer in education and could not bear the thoughts of his two daughters growing up in ignorance. He made all investigations concerning possible schools for them. His search led him to the only school at that time in the United States which was the American School for the Deaf in Hartford. John Macomber drove with his horse and carriage to Hartford taking Lydia first, and later Olive, also. The journey for him there and back took a week. The girls were taught the common school subjects, reading, writing, the language of signs and finger spelling.

James Austin Gifford (1842-1899)

James Austin Gifford was hired to run the Macomber farm. His father, Gideon Gifford, had a carriage shop in Adamsville just across Rocky Delano Brook from Brayton’s Garage. James must have seemed almost a part of the Macomber family, as his uncle Nathaniel Gifford was married to John Macomber’s sister Mercy, and his aunt Abby was the wife of John’s brother Caleb Macomber.

Olive Macomber (1827–1900)

Like her sister Lydia, Olive was born deaf. She never married and according to her niece, she must have lived a lonely life. Her niece recalls: “we children never communicated with her except by means of a small slate with a pencil attached. She seldom went out and few people could easily communicate with her. Aunt Olive always seemed to enjoy her canary which hung in the south piazza window. She made rag dolls called Polly or Tommy. They were very crude with flat heads and faces covered with some sort of shellac. Aunt Olive made many layettes serviceable but not beautiful, which she bestowed on many a baby for miles around.”

Leonard Macomber (1818–1873)

Leonard became Westport’s town clerk and was the first of three generations of Macomber men (his son John Austin and grandson Edward Leonard in his footsteps) to hold local political offices in Westport.

Nathaniel Gifford (1798-1878)

Nathaniel was associated with the Underground Railroad. He presided at abolitionist meetings in Adamsville, and attended the 1836 Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Convention.

Clarkson Macomber (1813-1835)

Amidst a community primarily focused on agricultural and maritime activities, Clarkson Macomber presents an unusually intellectual persona. At the age of 20, he was a studious and serious young man, employed as a teacher. He was preoccupied by his own poor health, with an interest in the Temperance movement, and in questions of religion, preferring to spend his time studying rather than helping on the family farm. Tragically his life was cut short by one of the most dreaded illnesses of the time, tuberculosis (also known as consumption). Classic symptoms of tuberculosis of the lungs included fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and chronic coughing and the spitting of sputum containing blood. Weight loss and the so-called ‘wasting away’ associated with TB led to the popular 19th-century name of consumption, as the disease was seen to be consuming the individual. His journal can be viewed at https://wpthistory.org/clarkson-macomber/

Frank Allen (1845-1848)

Francis C. “Frank” Allen was born in Westport on September 8, 1845 to New Bedford native Israel Allen and the former Emily Lucas of Plymouth. The couple were married in Westport in 1844, and Frank came along 10 months later. A second son, George was born in New Bedford in 1847. The boy would never get to know his older brother. In 1848, Frank, at the age of 2 years, was killed in an accident with a heavy gate. His body was brought to this graveyard and interred. His stone was given the epitaph, “safe in Heaven.”

Emily delivered another son on May 20, 1849. He, too, was named Frank C. Allen, in honor of his departed brother. This Frank lived to be 93 years old and eventually lived in California. None of the other family members were buried with young Frank, whose stone is among the largest and most ornate among the simple Quaker markers here. Stone repaired 2021.

Learn more at