Over the hill to the poor house: Revisiting the story of the Westport Town Farm

Posted on January 8, 2022 by Jenny ONeill

“Over the hill to the poor-house – me child’rn dear, good-by!

Many a night I’ve watched you when only God was nigh;

And God’ll judge between us; but I will al’ays pray

That you shall never suffer the half I do today.”

Will Carleton, 1904

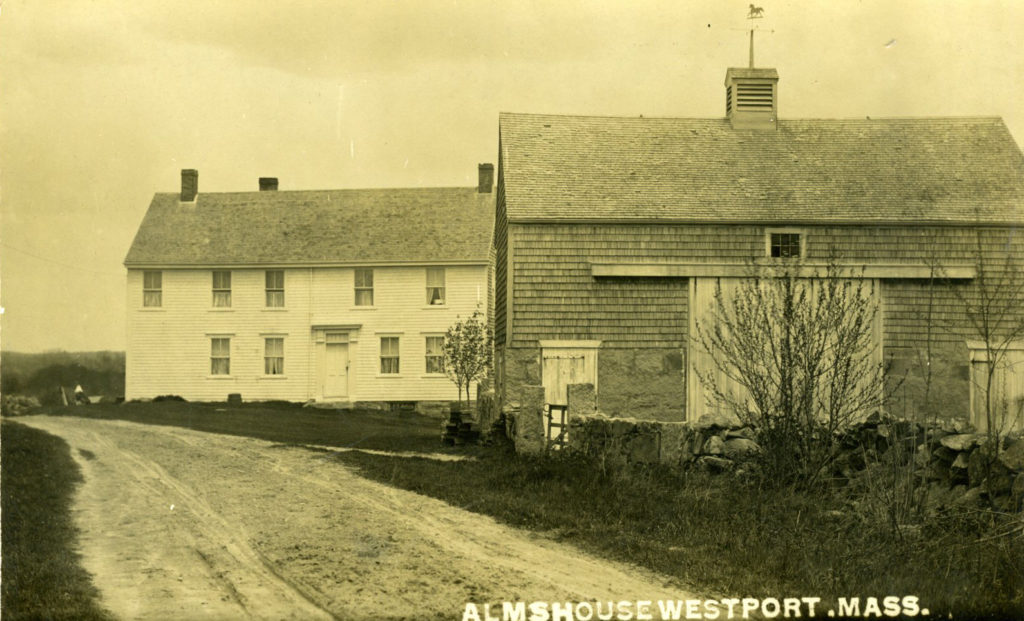

The Westport Historical Society has a temporary new home on the second floor of the Town Farm. Our move will allow for major repairs to the Bell School’s foundation. Plans for the long overdue rehabilitation of the Bell School will be shared in the coming months.

Although it is hard to ignore the irony of ending up at the Poor Farm, we are extremely comfortable in the beautifully restored Willcocks house with its expansive views to the river. Our time in this temporary new home also provides an opportunity to revisit the history of the Town Farm and to refresh our understanding of its significance.

The concurrent survival of a collection of preserved buildings and landscape with a deep and rich documentary record makes this topic especially attractive for research. The town farm was a focus of research for two notable local historians/preservationists, Geraldine Millham and Martha Guy. Fortunately, some of their work was captured in video recordings of public programs in which they presented their research. Their work is given further context by the comprehensive survey “The Poorhouses of Massachusetts” by Heli Meltsner, and by an unpublished thesis “Residence, Not Confinement” by Joshua Loyal Stewart, presenting findings of a 2012 archaeological dig which offers some unexpected insights into daily life at the town farm.

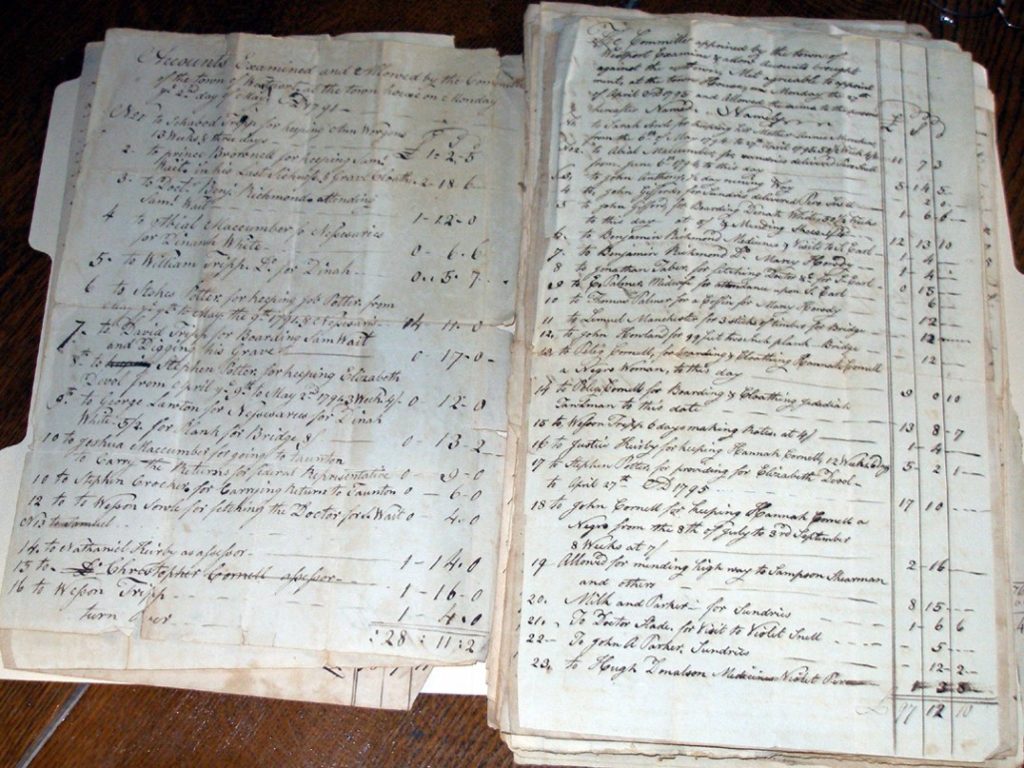

My goal is to share the wide spectrum of primary source material relating to the town farm, an archive that provides hints of life stories of hardship, sickness, mental illness and addiction as well as demonstrating “a strict regard to the principle of humanity and kindness toward that unfortunate class of our population.” The recently digitized town historical documents include the almshouse register, reports of the Overseers of the Poor, correspondence between towns regarding settlement of paupers, town farm accounts, and town meeting records. The Westport Historical Society has two collections of photographs relating to the town farm, including photos taken by Westport photographer David Allen and a collection documenting the building in the 1970s when it operated as a private rest home, Dea Rest.

A note about nomenclature

Terminology for sites that cared for the poor and infirm varied considerably. The Westport Town Farm has been known as the poor farm / town farm /almshouse / Infirmary. For most of the 19thcentury, Westport town records use the term “almshouse.” Today, it is known as Westport Town Farm. Town farms are also referred to as the asylum, poorhouse and workhouse.

The term “settlement” refers to an individual’s right to claim support from a particular town.

- A man derived his settlement from the town where he had paid taxes or owned land.

- A woman derived her settlement from her husband or father

- Children followed the settlement of their father

Pauper management prior to the Town Farm

Concern for the poor and elderly in 19thcentury Westport is one of the dominant themes of the town records, and was one of the main responsibilities of the selectmen. Prior to the town farm, individual townspeople would take in the poor, elderly and sick, a system known as venduing, when the town accepted bids for the care of paupers as illustrated by minutes of the town meeting in 1795:

“Voted that the Select Men be directed to fix on the time and place when and where they will meet, to vendue or dispose of the poor of this town, for the year ensuing to that person or persons that will keep them the cheapest on such conditions and restrictions as the Select Men shall there agree upon.”

In 1801, the system was altered to allow for one individual to take in all the town’s paupers:

“Voted that John Gifford take all the poor of the town of Westport for one year to support them comfortably in sickness and in health and to pay all necessary doctor’s bills… to find beding, cloathing … if any of the poor shall die before the twentieth day of May next, then said Gifford is only to receive a sum for their expense in proportion [to] the time they shall live … the said poor persons to be under the care and inspection of the select men, to see that they are comfortably provided for.”

What was life like at the almshouse?

In 1824, the town voted to purchase the Wilcox farm (built c. 1720) and repurpose it as an almshouse. For 125 years this site was home to Westport’s “poor, intemperate, insane, and elderly.” The “family model” of the poor farm not only provided its residents with accommodation, meals, and healthcare, but was also designed to encourage a sense of community, and indirectly, to facilitate moral rehabilitation.

The family model of the poor farm is reflected in the daily management by a warden (or superintendent) and the matron, often a husband-and-wife team, whose children would also participate in the management of people and facilities.

The superintendent, often with help from his sons and with participation of the inmates, managed the farm activities. Records show that the town farm had dairy cows, pigs, poultry, grain and vegetables. Hay and salt-hay created the largest percentage of annual income.

By the late 19thcentury, the farm had become comparatively productive. It sold eggs from 222 chickens, milk from 7 cows, meat from pigs in addition to the subsistence farming of vegetables and crops.

The matron was responsible for the housework, managing meals and some healthcare, often with the assistance of her daughter. She was the “mother figure” of what the Overseers of the Poor referred to as “the family circle” of that institution. Her charges also included orphans, and young truants who attended the short-lived “farm school.”

The town hired a local doctor to provide more skilled medical attention. Those with more serious mental illness were moved to the state-run mental asylum in Taunton.

Annual state inspections give us a glimpse of conditions within the almshouse:

Annual Report of the State Board of Charity

WESTPORT Population 2,928. Inspected July 24 1913. Warden Aaron Besse, matron Mrs Besse salary 400 served here seven months. Warden has six rooms. One room with one bed set apart for hospital use. One sitting room. Nine sleeping rooms with nine beds. One bath room without direct supply of water. Two privies. Heating by steam. Lighting by oil. Ten tramps during year separated from other inmates, lodged, fed, required to work one hour at wood pile. Forty five acres of land, one half an acre ploughed, sixteen acres tilled. Chief products milk and vegetables. Valuation of almshouse property $1,505.18 Total annual cost $1,213.90 net $986.22.

“The possibility of fondness”

An archaeological dig conducted in 2012 uncovered some discoveries that challenge our assumptions about the town farm and its “inmates.” Presenting the findings in a thesis titled “Residence, Not Confinement,” Joshua Stewart questions whether the town farm was a place of confinement and control such as a prison or asylum. He suggests that the evidence might indicate that it was a place of refuge, regarded as part of the town, not other than, “making the most of it in a world of sparse charity.” Stewart considers the unique nature of small town farms, which clearly had little in common with the large city workhouses and state level mental institutions.

The dig uncovered a large amount of ammunition, indicating the presence of seven firearms, most likely used for hunting during the Great Depression. According to Stewart, this is further evidence of a shift in the town farm’s role from providing support for the poor, insane and intemperate to caring exclusively for an elderly (and less dangerous) population.

The dig also uncovered objects of personal adornment, including 19 buttons which provide some further clues about the nature of the poor farm. Among the collection is a hard rubber button worn for 18 years before being discarded, indicative of long-term thrifty retention of clothing. The dig also uncovered a bronze button made in the UK for the US military, retained and perhaps repurposed by a resident. Cumulatively, the small finds suggest “a community with social distinction, personal identity, and diversity rather than one of institutional similarity.”

Conditions within the almshouse were well documented and publicized through the annual reports by the Overseers of the Poor. They sought to “promote a just and sound economy in that department of our Town affairs, and at the same time have a strict regard to the principle of humanity and kindness toward that unfortunate class of our population.”

Benevolence was demonstrated in 1879 by Mr. A. R. Gifford who“made the hearts glad of the inmates of the almshouse, by furnishing them a Turkey Dinner on Thanksgiving day.”

The Almshouse Inmates

The number of paupers at the town farm fluctuated over the decades:

1840 — 37 paupers

1880 — 11 paupers

1930 — 7 paupers

The almshouse register notes the reason and date for departure. Many were simply discharged, but other reasons included:

- Went to live with another individual

- Went to work for another individual

- Ran away

- Walked away

- Sentenced for being a common drunkard

- Sentenced for 3 months for neglecting to provide for family

- Illegitimate baby taken by family member

- Committed to Taunton Hospital

- Buried by his friends

- Returned to their family home

The following notes are included among the lists of names and dates in the almshouse register

1859 Remarks on Paupers

Samuel Wordell – lived and died a batcheldor and was worth in the best of his days about two thousand dollars.

Zira Wordell was insane about six years prior to his death, was the son of Tabor Wordell – lived due north from Abial Davis.

Richard Macomber, an old batcheldor loves rum better than food came here by drinking to much; is the brother of Varnam Macomber, a shoemaker at westport point.

William Macomber brother of Johnathan to married three times had some children, all dead but one and that he don’t know where he is.”

Town farm historian Martha Guy has delved further into the stories of three town farm residents, illustrating three contrasting personal circumstances, each leading to the almshouse. (You can watch her presentation at https://vimeo.com/483229833 and https://vimeo.com/479870723)

To summarize her research:

Illness

Judith Thompson born in Middleborough, married Westporter, David Thompson. They settled in Westport, building a house at 588 Gifford Road. However, by 1846, they experienced financial troubles leading to foreclosure. Judith returned to her family home in Middleborough and David left for the California gold fields. By 1859 Judith was confined to her bed, suffering from a debilitating illness and her husband was no longer able to support her. Following a lengthy interchange of correspondence to establish her settlement in Westport, she was transported from her brother’s residence in Middleborough to the Westport almshouse, as her brother was no longer able to care for her. She spends the rest of her life, 13 years, at the town farm. When she arrived, there were 23 residents at the town farm. Among them:

- Freelove Tallman, noted as having a deformity

- Eunice Tripp, aged 77, insane

- Lucy Gifford, aged 34, insane

- Caroline Pettey, idiotic

- Sarah Fish with 3 boys aged 14, 5 and 1 ½ years

- Ruth Sowle, aged 14

- Several Crocker children under the age of 10, no parents listed.

References to the “insane” and “idiotic” appear frequently in the almshouse records, but, as Martha Guy points out, they were “subjective categories” rather than medical evaluations.

Addiction

Born in 1793, Ramon (Raymond, Raimon, Raman) Castino, was the eldest of eight children. His father, a wealthy man, died in 1810 and Ramon was appointed as the executor of his will. Although Ramon discharged all outstanding debts, there are indications that he suffered from various addictions. In 1812, Ramon submitted a sizable bill of 32 dollars to the probate court for attending and furnishing liquor at the auction of his father’s sloop. The account books kept by Dr. James Handy show that Ramon received repeated doses of opium. By 1845, Ramon was admitted to the almshouse as a pauper where he died in 1861. His life is succinctly described in the almshouse register: “Raman Castano – was married – and was once a welthy man, he lost his property by forgery & drinking – he has no children.”

Orphaned

Born in 1840, Caroline Tallman was identified in the census as a “mulatto.” Her mother was Betsy Tallman, her father was unknown. By 1842, Caroline had been admitted to the almshouse as an orphan where she remained until the age of 15. In 1859, she was taken to live at the Head of Westport with a former almshouse warden Thomas J. Allen and his wife. The census lists her occupation as “milliner.” The household moved to Dartmouth but, by 1859, correspondence between Dartmouth/Westport Overseers of the Poor suggests that she was once again destitute and no longer a member of the Allen household. Martha Guy noted that by 1859, Caroline had married Abraham Maxfield of Dartmouth and by 1870 she lived with her husband and five children in New Bedford. Several questions remain. Was Caroline of Native American descent as suggested by the identification as a “mulatto”? What caused her destitution in 1862? What was her fate — continued stability as suggested by her marriage or a return to the poor house?

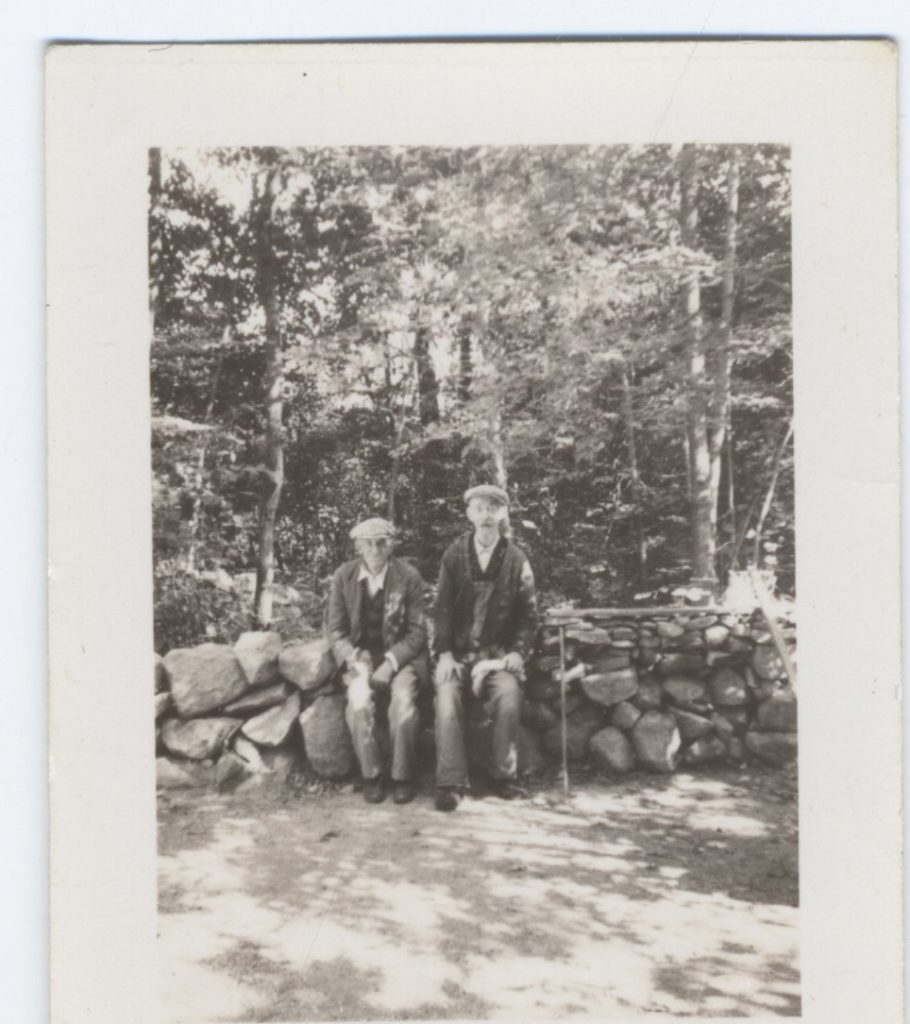

Long-term residents

Although most residents passed through the doors of the almshouse for a brief time, there was a core group of individuals who remained in the almshouse for decades:

- Lurana Manchester, admitted in 1841, noted as being deaf and dumb, Lurana spent the next 50 years at the town farm. She is listed as a pauper at the town farm in 1899.

- Caroline Pettey admitted 1841 at the age of 32, remaining there until 1899.

- Lucy Gifford, admitted 1857, remaining there until her death in 1898.

Over the years, this group shared the sitting room and took meals together. Several of these individuals left the almshouse briefly, possibly staying with family members. With a population of about 2,000, 19thcentury Westport was a small close-knit community, and it is likely that many of the almshouse residents had family members nearby who for various reasons were unable or unwilling to care for them.

Tramps and travelers

The tramp house (or carriage shed) stands to the north of the main town farm building. It provided a separate lodging space for transients in a room with barred windows and a heavy oak door. The tramp, as an able bodied but homeless person, traveling from town to town begging for private charity, was in a sense the opposite of a pauper with legal settlement in a community (Heli Meltsner). Some tramps may have been returning Civil War soldiers, others “rode the rails” of the newly constructed network of railroads.

Milton Borden, interviewed in 1976, recalls a few details about these individuals:

“In my younger days, what stands out in Westport was what some people call them—tramps, and some people call them hoboes. I was about five years old in 1908. In fact, they used to come down and travel from town to town—Little Compton, Dartmouth, and Westport; and I was very much interested because, at that time there was what they used to call the “town farm,” because in the law, they had to be put up to two or three days at a time—if they stayed any longer, they were forced to work. They never got any money.

What was the Westport Town Farm? That’s where they stayed and they had little places where they stayed. …The shed was where the tramps lived. The difference between the tramps and the hoboes was that the hoboes were classed a little higher. After I got a little older, I could tell the difference myself. You could tell the difference between the two – they could always tell the difference.

Time hasn’t changed anything. Today there’s people on the road who you might call tramps.”

Tramps were generally feared by townspeople as recounted by Marianna Macomber:

“Another fear especially in the spring was of meeting tramps. These stragglers having spent the winter under cover began to travel the country roads. Many women began to keep doors locked as I was not the only one who feared them. The farmers dreaded them too, as they would often go into a barn after dark to sleep on the hay causing a fire hazard. For this reason the town maintained a tramp house at the Town Farm. By getting a permit from the Overseers of the Poor a tramp could have a bed and breakfast. Since my father was on the Board, just at dusk of a spring evening in May or June, the two worst months, it was a frequent occurrence for a tramp to appear at the door for a permit, but at any time of day they might come along asking for food.”

As noted in the almshouse register, many tramps arrived “with a Good Share of Lice.” They received crackers, cheese, salt fish, water, and accommodation in a sparsely furnished shed, supplied with mattresses, quilts, wood, candles, and matches. By law, tramps were required to work in return for bed and board. Not surprisingly tramps were known to run away before completing the so called “work test.”

The almshouse register also records the presence of “travelers” — providing their full name, age, residence, complexion and height. Their presence implies that the almshouse was used as an inn for short stays. Many of these travelers came from Ireland, England, Scotland and even as far as Denmark. Some may have been mill workers traveling between Fall River, New Bedford, and Lowell.

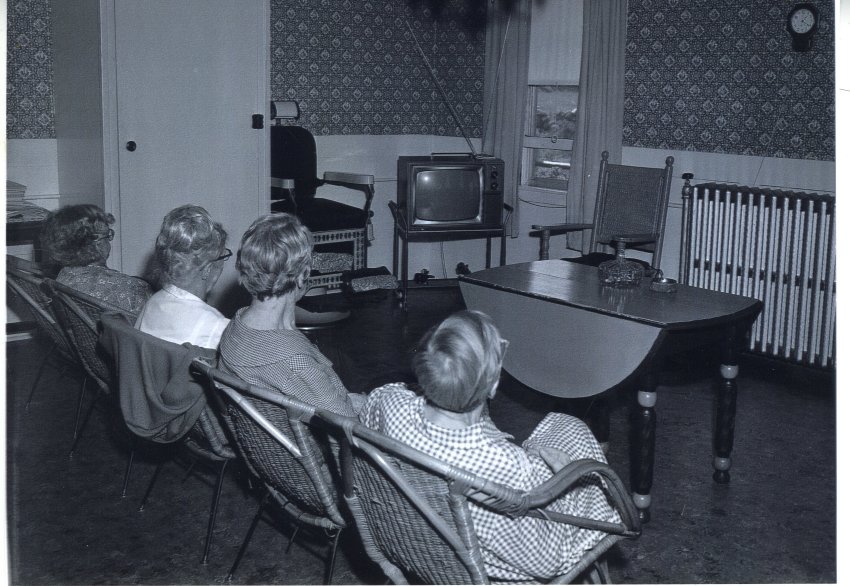

The Infirmary and Dea Rest

“The town farm closed when the need for it had disappeared.” (Joshua Stewart)

Nevertheless, Westport is notable for being one of the last towns, by many decades, to close their poor farm. The establishment of the Social Security Act eventually brought change to the town farm. By 1930, the poor farm had become a place to house the elderly, known as The Infirmary. The Overseers of the Poor were renamed as The Board of Public Welfare.

In 1956, the town voted to approve the permanent closing of the Infirmary, and approved the lease to Mrs. Dorothy Hathaway “so that she may operate it as a home for the aged or convalescent persons.” It became known as Dea Rest. A collection of photographs of the interior and exterior show immaculately furnished rooms with communal-style living and dining rooms.

Town Farm Preservation Effort

By 1978 Dea Rest had become a “white elephant for the town.” The proprietor failed to pay rent, and there were worries about the building’s safety in the event of a fire. The selectmen considered renting it to large families from Fall River or for use by the Council on Aging but the expense of rehabilitation and the need to meet fire safety requirements remained an obstacle.

Recognizing the historical value of the property and fearing for its future, Geraldine Millham sought to save the property from demolition and development. Working under the auspices of the Westport Historical Commission with Pete Baker and Steven Delano (WHC chair), she proposed a scheme to preserve the town farm by creating self-financing rental apartments. Newspaper articles recount the “emotional controversy” to restore the Town Farm in 1980 which met with some resistance at the town meeting.

“The property has given us nothing but trouble, it should have been torn down,” commented one town meeting participant.

However, after much debate, town meeting voted to support the project. Shouldering the responsibility for the ongoing care and management of the property, Geraldine succeeded in making the town farm self-supporting through rental income.

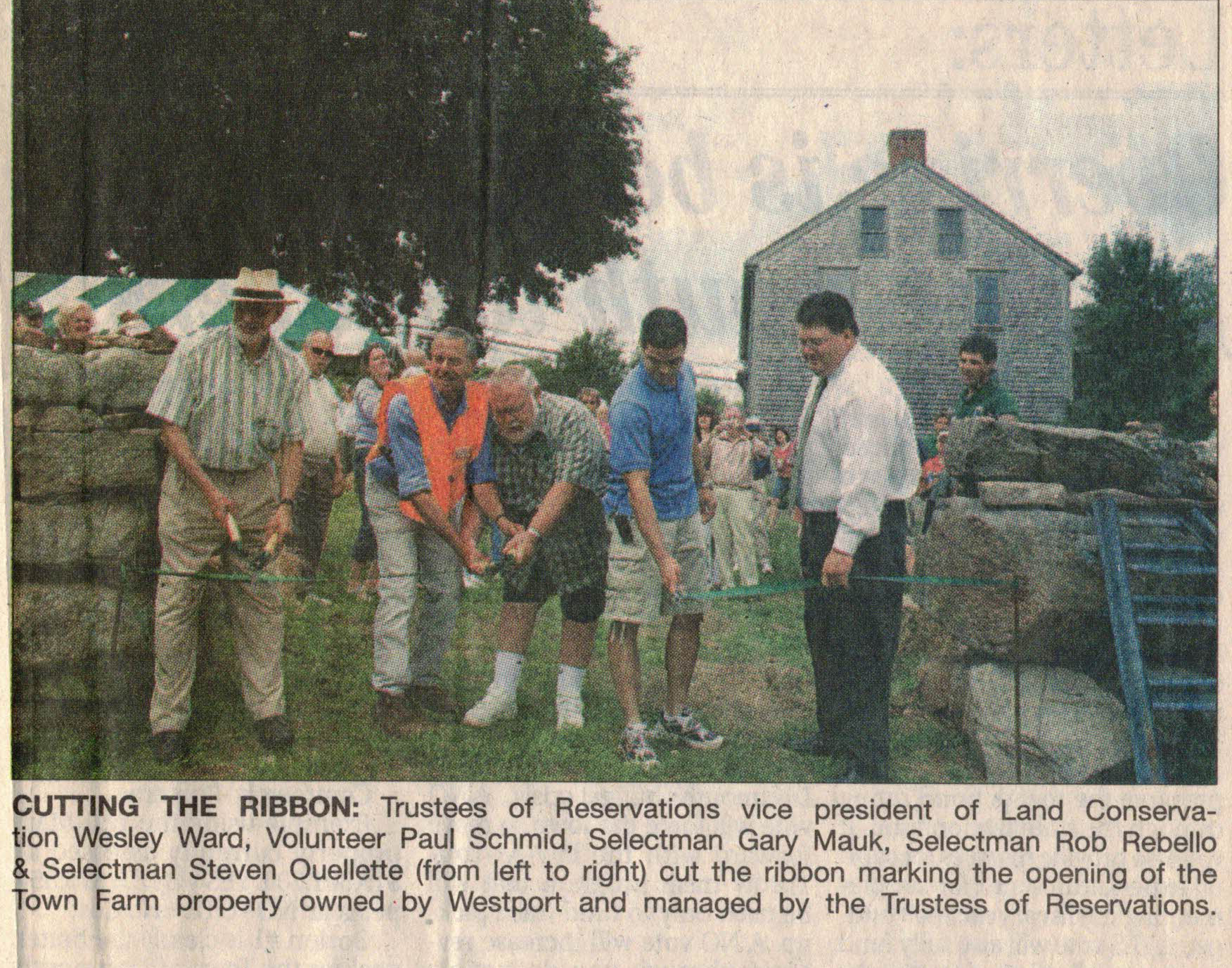

By 2006, the town farm had entered a new lease of life under the management of The Trustees of Reservations. The buildings were restored, transformed into offices and a meeting space for TTOR and the Westport Land Conservation Trust. The surrounding land became the site of a productive community farming project, producing over 2300 pounds of fresh vegetable and fruit.

The utilization of the land and buildings continues to evolve. Today it is a popular destination for walkers (and their dogs). The open landscape and cleared fields, delineated by stone walls, offer stunning views to the river — a quintessential Westport experience combining fascinating stories of past lives, historic architecture and natural harmony. Fortunately, its story is deeply enriched by the documentary evidence that has survived long after the last inmate passed away.

References

The Westport Town Farm is located at 830 Drift Road, Westport Massachusetts

One of the key documents is the Almshouse Register listing residents, date of admittance and discharge. A PDF of the transcribed register is available here:

Historical documents available on the Westport town website

https://www.westport-ma.com/historical-documents

This collection represents the work of the Overseers of the Poor including communications between towns, correspondence with the Overseers of the Poor, town farm accounts, almshouse register and ledger, and other documents relating to the town’s management of paupers.

https://www.westport-ma.com/historical-documents/pages/almshouse-town-farm-assistance-poor

Of special interest is the collection of correspondence establishing settlement (Westport residency through property ownership/taxes) for individuals requiring town aid.

Letters and journal of the Westport Overseers of the Poor 1848-1887

https://www.westport-ma.com/sites/g/files/vyhlif7356/f/pages/1848-1887_westport-overseers.pdf

1859 Valuation Town Tax

1860-1880 Almshouse Register

1870 Overseers City of New Bedford Nancy Pierce

1874-1910 Paupers Supplies

1875-1885 Almshouse Expenses

1877-1881 Overseer of the Poor Records

1885-1891 Orders in Force

1885-1892 Almshouse Expenses

1889-1894 Audit Book

1892 Order for Aid

1893-1911 Outside Paupers

1893-1914 Inside Paupers

1895-1901 Town-Records PART A

1895-1901 Town-Records PART B

1902-1908 Town-Records PART A

1902-1908 Town-Records PART B

1902-1908 Town-Records PART C

1909 Overseers Poor

1909-1910 Town-Records

1912-1924 Outside Poor

1914-1925 Supplies-to-Almshouse

Alms House Records

Mary-Bulls_Eng

Tripp-Brothers_Phebe_Briggs

Westport Historical Society collection

Town of Westport Historical Documents

Stewart, Joshua Loyal. Residence, Not Confinement: Daily Life at the Westport Town Farm, A Thesis. University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2013

Meltsner, Heli. The Poorhouses of Massachusetts. McFarland Co. 2012

Videos of presentations by Martha Guy and Geraldine Millham