The Buildout at Westport Point in the 1770s by David C. Cole and Richard Gifford

Posted on November 16, 2020 by Jenny ONeill

Until the 1770s, Paquachuck Point (now known as Westport Point or The Point) was little more than open pasture. It was a North-South peninsula surrounded by an estuary with a narrow opening to Buzzards Bay and the Atlantic Ocean at its southwestern most extremity. There was a “way” now known as Main Road that ran down the ridge of the peninsula to the water and docks at the southern tip. Christopher Gifford had purchased 60 acres of open land at the southern end of the peninsula in 1699 from Daniel Wilcox.

At some time in the first half of the eighteenth century a house was built on the east side the way and a gate installed to control, and probably charge for, passage to and from the Point. There appears to have been considerable movement of livestock down this laneway to the point from which they were then transported by small boat to graze on the salt marshes on the south side of the river.

For 70 years neither Christopher Gifford nor his son Christopher II sold any of this property. But Christopher Gifford III, who inherited the property in 1767, began to sell plots of land in 1770.

The sale of land at the Point that began in 1770 coincided with the growing conflict between American colonists and their British overlords that disrupted coastal trade and led persons linked to such trade to look for safe havens that would be less susceptible to British disruption and domination. A number of residents of nearby Rhode Island, with its readily accessible Sakonnet River and Narragansett Bay, were attracted to the harbor at the Point because the large English square-rigged naval ships would in all probability be unable to penetrate its narrow U-turn entrance and shallow sandbars.

As a consequence of these factors, the decade of the 1770s saw a burst of construction of both houses and workshops at the Point. This paper seeks to explore briefly the external pressures from the revolutionary conflict, then describe in greater detail how they were responded to on the local scene throughout the decade and, finally, to recount how this historic area has been preserved through the subsequent 240 years despite many challenges. A companion document prepared by Sean Leach traces the history of Town-owned property around the waterfront at the tip of the Point.[1]

The historical setting for activities at Westport Point

To gain a better understanding of the developments at Westport Point in the 1770s it is important to recall some of the major events leading up to and throughout that period. Beginning in 1764, the British Government sought to impose duties on imports into the American Colonies as a source of revenue for the British Crown. These started with the Sugar Act of 1764 that put a tax on sugar and molasses from non-British ports. This was followed by the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townsend duties of 1767. These measures were all seen as taxation without representation and led the Colonists to devise alternative sources of supply that would not be subject to the import duties administered by British custom officials. Many ship owners and seamen in the American Colonies undertook to pursue such trade which the British labeled as smuggling but the local people considered legitimate trade.

This conflict reached a local apogee in June 1772 in The Gaspee Affair when an American schooner, Hannah, tricked the British customs vessel Gaspee into running aground in Narragansett Bay.[2] A local raiding party out of Providence, led by prominent citizen John Brown, quickly captured the vessel, off-loaded the captain and crew and then burned it to the waterline. In the aftermath of this event, the British beefed up their patrol fleet and the colonists searched for safer harbors where they could not be harassed and followed. The Boston Tea Party in December of that same year led to further efforts at suppression by the British and evasion by the American colonists.

The British Navy set out blockades along the south coasts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. The important town of Newport and its harbor became a major base for the British forces. From there the British established their dominance over Narragansett Bay and the Sakonnet River. At that time, some residents and ship owners moved to the Westport River area because it provided a safe haven that the large square-rigged British naval ships could not enter. American Schooners – with shallower draft and fore-and-aft rigging were much more able to squeeze through the narrow opening to the Westport harbor when winds and tides were favorable. While they were constrained by the blockade, American ships were safe so long as they remained within the Westport River itself.

A second example of the safe haven nature of the Westport River is seen in the British attack on Dartmouth on June 5, 1777.[3] Bypassing the main entry into the Acushnet River that was protected by Fort Phoenix, the British sailed instead into Clarks Cove with two frigates, a brig and thirty-six transports carrying 4,000 soldiers. They met little opposition and sent the soldiers through the towns of Bedford and Fairhaven burning buildings, homes and waterfront facilities. They reportedly destroyed seventy vessels including eight large ships, some of which had been taken as prizes and brought to Bedford Harbor by American pirates.[4] The damage was severe. But Westport Point and the River were not attacked then or at any other time during the war.

There are stories that British warships shot some cannon balls into the area of Westport during the war, but they reportedly did little damage. Westport Point remained a safe haven from which local sailors could venture forth under cover of darkness or adverse weather and carry out their activities. Local historian, Richard Paull, described these activities as smuggling, but the owners and seamen undoubtedly saw their activities as legitimate, patriotic trade and probably also, in some cases, pirating. Local hero Paul Cuffe made numerous trips probably out of either the Slocums River or the Westport River in a small sailboat called a shallop, delivering supplies to the people of Nantucket throughout the war, successfully avoiding both British and pirate ships on all but three occasions.

Early ownership of the land at Westport Point (Paquachuck Point)

Daniel Wilcox, the earliest recorded “owner” of Westport Point, derived his right from the quarter share of Dartmouth land given to him by his father-in-law, the Mayflower passenger John Cooke. Cooke received a one thirty fifth share of the 1652 purchase of a 70,000-acre tract from the Wampanoag Chief, Osamequen, and his son Wamsutta that was later labeled Dartmouth and managed by the 35 Old Comers who constituted the Dartmouth Proprietors.[5] John Cooke lived in Fairhaven and it is unclear whether his son-in-law, Daniel Wilcox, ever lived at Westport Point. By tradition, it is asserted that he lived on other land on lower Pine Hill Road. He also owned the land where the Westport Town Farm now is on Drift Road, his son Stephen Wilcox building the oldest part of the present structure there around 1730. Daniel also owned 100 acres in Acoaxet deeded to him by the sachem Mamanuah in appreciation for assistance to the Indians of Acoaxet rendered during King Philip’s War.

Daniel Wilcox, in the years following his arrest and escape in 1692 for his involvement in Almy’s Tax Revolt[6], was a refugee in Portsmouth. He eventually was pardoned when he granted a 100-acre parcel in Tiverton on the west side of South Watuppa Pond to the Massachusetts Bay authorities. This parcel was the first location for the Watuppa Indian Reservation. His broker in that transaction was Col. Benjamin Church, who during King Philip’s War had used Wilcox as in interpreter, most notably at Church’s parlay with the squaw sachem Awashonks at their meeting at Treaty Rock.

The first deeded transfer of land at what was Paquachuck Point (now Westport Point) occurred in 1699 when Christopher Gifford purchased 60 acres of land from Daniel Wilcox. Christopher Gifford reportedly built a house on this property by “ye great gate going down to ye ferry point” but probably never lived in it. He gave 8 acres of land and a house to his son Christopher II in 1730 and Christopher II ran a ferry from the tip of the Point across the river to the area called Horseneck and charged a toll to carry people, animals and wagons. Christopher II received the remainder of his father’s lands at Paquachuk Point in 1736, and in his will of 1767 gave the southern half of the 60 acres to his son, Christopher Gifford III.

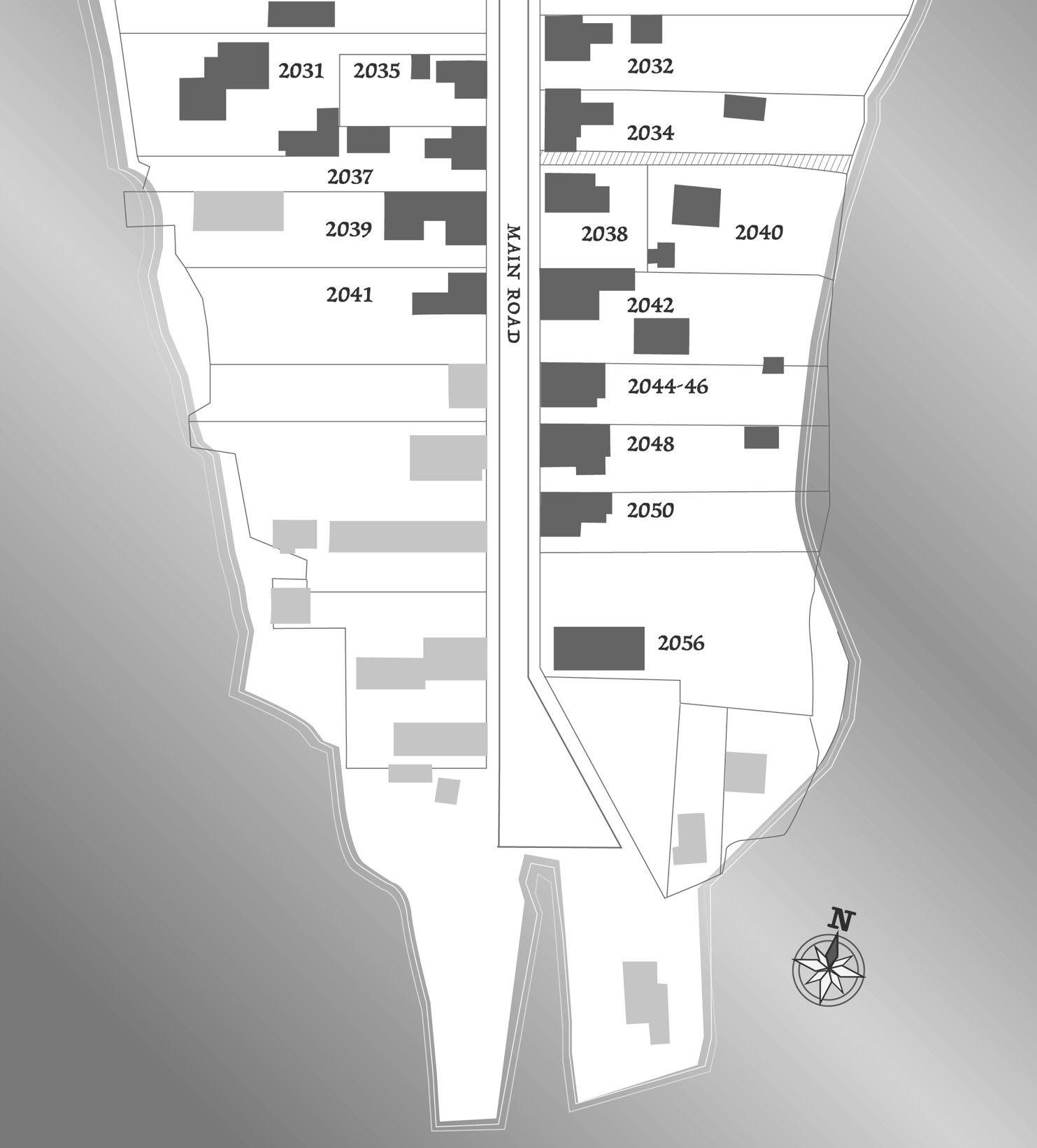

The following image shows a GIS map of the lower part of Westport Point as of 2020 and indicates the current street addresses of the houses referenced in this paper.

Constructing houses and other buildings at the Point

In 1770 Christopher III began the process of selling off parcels of land at the lower Point to several persons. The first such transaction involved the property on the southwest side of the Point which was sold to Stephen Davis, a carpenter and shipbuilder born in Freetown in 1738 and living in Dartmouth in 1770. The property was bounded east “on the way” for 20 rods or 330 feet, the northern boundary ran west 7 degrees south for 13 rods (215 feet) to the river and thence along the riverbank, or salt water, to the point of beginning. Christopher Gifford III was the owner to the east and the north. Because the southern tip of the Point is not precisely defined in the deeds, it is not possible to know exactly where the northern boundary was. It was most likely the northern boundary of the lot that Stephen Davis sold to Isaac Cory in 1777.

Stephen Davis probably constructed some buildings related to his boat building and repair business soon after his purchase of this property. He also constructed a house at the northern end of the property sometime before March 1777 when he sold a lot with his dwelling house, stable and other buildings to Isaac Cory. Although Stephen Davis appears to have been the first purchaser of property at the Point, it is unclear if he was the first one to build a house there.

The sequence in which the different houses were constructed throughout this decade is difficult to determine because the only dates to go by are the dates on the deeds transferring ownership and one cannot say with certainty how soon thereafter the house was actually constructed. The Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) official forms prepared by Richard Wertz, Geraldine Millham and others for these properties appear to give the best available indicators of dates of construction and they provide the basis for the following discussion.[7]

The first house to be built at the Point, according to the MHC records, was on the east side of the way (now approximately Main Road) on a property sold by Christopher Gifford III to Stephen Kirby in 1774. The current address of this house is 2034 Main Road.

The MHC records indicate that there were two houses built in the following year, 1775. The first was by Stephen Davis on the west side of the way on the property that he had purchased from Christopher Gifford III in 1770, with the current address of 2041 Main Road. A second house was built by George Brightman on property he purchased from Christopher Gifford III. He then sold that property with a house on it in 1775 to Benjamin Davis, a cousin of Stephen Davis. This house is now at 2048 Main Road and on the east side of Main Road.

In 1776 there were two property sales by Christopher Gifford III that probably resulted in two more houses being constructed at the Point that year. Both of these buyers were from Little Compton and were housewrights. One was acquired by John Wilbour at what is now 2037 Main Road, and the second by Wilbour’s brother-in-law, John Head, at 2035 Main Road. The best evidence that they each constructed houses on these properties and were living in them before December 1777 is that both men were listed at that time on a muster role of a Dartmouth Company led by Captain William Hicks that contained many familiar names of Westport residents including Benjamin Davis but not Stephen Davis. (Ellis, p. 87.)

There is no recorded deed from 1776 for the sale of the property by Christopher Gifford III to John Wilbour, but he is listed as the abutter to the south on the John Head deed and again as the northern abutter on a deed executed in 1778. The deed for the John Head purchase was signed 18 June 1776, but not registered until 13 November 1782, indicating that Christopher Gifford III was not inclined to register his deeds of sale in a timely manner. John Head sold this property to Isaac Cory in 1787.

The original deed for the sale to John Wilbour was never registered. A new deed was executed between Gifford and Wilbour on 6 March 1798 and recorded the same day as a deed of sale for this same property from John Wilbour to Phillip Cory. The Gifford to Wilbour deed records a payment of $65 whereas the Wilbour to Cory deed records a payment of $340 and says that the sale includes the buildings and appurtenances on it, presumably the house and outbuildings that John Wilbour built on the property probably in 1776.

There are two aspects of these Wilbour deeds that are worth noting. The first deed from Gifford to Wilbour cites a price of $45. In 1776 when this transaction presumably took place, US Dollar currency did not exist, so this is perhaps an estimate of the value of the property at that time, or of the amount actually paid. The deed from Gifford to Head for the immediately adjacent property was stated as £9. If the same price was paid for the Wilbour lot, the exchange rate used in 1798 for the estimation was $5 to the pound.

A second interesting point concerns the boundaries of the Wilbour property. The measurements of the John Head property were 50 feet north to south and 110 feet east to west. This meant it was just a house lot along the road and had no connection to the river, which is still the case for this lot today. The Wilbour lot is quite likely to have had the same dimensions, 50 by 110 feet, at the time of the transaction in 1776. But in 1798, when the belated deed was written and recorded, the dimensions were very different. The northern boundary starts at the highway and runs along the line of the John Head property, that was, by then, owned by Isaac Cory, for 110 feet – similar to the depth of the Head lot – then runs south 25 feet to the middle of the Wilbour lot and then west to the river, south along the river for 20 feet and then east along the line of Isaac Cory’s store lot to the highway. Abutting properties to the north are Isaac Cory and William Watkins and to the south, Isaac Cory’s store. There must have been an agreement between Christopher Gifford III and John Wilbour, perhaps when Gifford sold the lot to William Watkins in 1782, to extend the Wilbour property down to the river by adding a parcel that is 25 feet north to south on the east side and only 20 feet at the river. These dimensions have carried forward to the present day. Whether or how much John Wilbour might have paid for this extension is not a matter of record.

The William Watkins property (2031 Main) was sold to Watkins by Christopher Gifford III in 1782, and the lot for Isaac Cory’s store was acquired by Isaac Cory in 1778 from a Benjamin Crandall. The land that subsequently became the Watkins property was still owned by Christopher Gifford III in 1776 and was so designated on the John Head deed.

The next property transactions of interest involved Isaac Cory, a resident of Tiverton, Rhode Island, who moved to Paquachuk (Westport Point) in 1777. The first is a deed signed on 3 March 1777 between Stephen Davis and Isaac Cory that conveys “land with my dwelling house, stable and other buildings” for which Cory paid £240. The property ran for 67 feet along the way and abutted Stephen Davis’ property on the south, the river on the west and a property belonging to Benjamin Crandall on the north. The current address of this house is 2041 Main Road. This deed was transferring the dwelling house that Stephen Davis had built perhaps for himself at the northern end of his 1770 purchase to Isaac Cory who made it his residence at the Point in 1777. According to the MHC records, Isaac Cory and his descendants lived in this house (now 2041 Main) for 60 years until 1837 when it was sold to Jethro Howland.[8] Isaac Cory and Isaac Cory Jr. lived in this house for nearly 6 decades whereas Stephen Davis lived there for only a few years.

The following year, 1778, Isaac Cory purchased the property immediately north of the property described above from a person named Benjamin Crandall, a cousin of John Wilbour, for £63. The address of this property now is 2039 Main Road. There is no record of how Crandall acquired the property.????? The boundaries began at the northeast corner of Cory’s existing lot and ran 50 feet north along the way, then 14 rods (231 feet) west to the river, then fifty feet south along the river and then east along Cory’s line to the point of beginning. According to the MHC records on this property, Isaac Cory built the building on this property around 1795 and it housed his store. Some years later, the year is disputed, Isaac Cory and his son, Isaac Jr. built the store at 2056 Main Road, now the Paquachuk Inn, and transformed the property discussed here (2039 Main) into their residence. This may have occurred at the time they sold the property to Jethro Howland in 1837.

The last property to be sold by Christopher Gifford III on the west side of the way before 1800 was the one sold to William Watkins of Little Compton that is mentioned above, now 2031 Main Road. Watkins paid £12 and the deed was signed on 29 November 1782 and recorded on 16 December 1783. This lot was bounded north by Christopher Gifford’s pasture, west on the river, south on John Wilbour’s and John Head’s properties and east on John Head’s property and also on the way. This segment along the way was 12 feet long and provided space for a lane from the way to the main part of the property near the river. At some later date this lane was reportedly given the name of Thanksgiving Lane by Christiana B. Allen, a subsequent owner of this property.

Houses on the East Side of Main Road

Mention has already been made of two houses built on the east side of Main Road in the 1770s. The first one was built by Stephen Kirby probably in 1774 at 2034 Main Road. The second was built by George Brightman, in 1774 or 1775, at 2048 Main Road and sold to Benjamin Davis in 1775. Benjamin Davis was a cousin of Stephen Davis, who had purchased the property across the road in 1770, and probably built a house there, also in 1775. Benjamin Davis is reported to have operated a distillery at the Point.

In October 1777 William Earle Jr. sold a lot with a house on it to Lemuel Bayley of Little Compton. There is no recorded deed by which William Earle Jr. acquired this lot, but he probably bought it from Christopher Gifford III that same year and constructed the house. The lot was 45 feet north to south and ran from the highway to the river. It was abutted on the south by Benjamin Davis property and on the north by Hillard Mayhew’s property. The current address of this property is 2044-2046 Main Road. The double address is indicative that this was a duplex structure and Lemuel Bayley is recorded as having sold half of the house in 1777 to Lemuel Sowle, a mariner, and the other half in 1786 to Henry Smith, another mariner.

There is no record for the original sale of land or construction of the southernmost house on the east side of the road that is now 2048 Main Road. According to the WHC records, this house may also have been built in 1775, but the first known record is from 1785 when Joseph Allen, a blacksmith, and his wife Prudence are named in another deed. The first recorded transaction for this property is a deed relating to the sale of the house and lot in 1787 to William Robinson, a mariner.

George Brightman built another house, now 2038 Main Road, in 1782 and may have lived there until he sold it to James Sisson in 1793. There was a laneway running down to the water on the north side of this property and between it and the Stephen Kirby house at 2034 Main Road. Two houses were built on that lane way probably in the early 1780s. There is a record of Christopher Gifford III selling the property on the south side of the lane way to Ephraim Manchester in 1781 and Manchester may have built the house that is still standing soon thereafter. There was a second, similar house on the north side of the lane way, but it was destroyed many years ago probably by fire.

One additional house was built on the east side of Main Road in this period. It is the house at 2032 Main Road, just north of the original Stephen Kirby house. In 1780 Joseph Devol sold this 1/4-acre lot with a house on it to Lemuel Bayley, the same person who owned the duplex at 2044-46 Main Road. It is not clear whether Lemuel Bayley ever lived in either of these houses. He does not appear in the 1790 census, so may have just owned them temporarily or rented them to others.

Spec houses?

There has been some discussion as to whether some of these houses were “spec houses” built by housewrights who intended to sell them soon after construction or were built as homes for the property owners. The two houses built by George Brightman would appear have been spec houses as would the house built by William Earle Jr. The house built by Stephen Davis at 2041 Main Road in 1775 and then sold to Isaac Cory in 1777, may have been a spec house, but it may also have just been a house that Stephen Davis built for himself and then sold to Isaac Cory who was moving his base of operations from Tiverton, Rhode Island to Westport in response to the wartime pressures.

The two adjacent houses on the west side of Main Road built in 1776 by John Wilbour and his brother-in-law, John Head, may have started out as spec houses since both of them were housewrights. But the fact that John Head did not sell this house until 1787, and John Wilbour until 1798 would suggest that either their speculation was not successful, or, like so many subsequent residents of Westport Point, they decided it was a pretty good place to live. They may also have played roles in the construction of other houses that were built at the Point over the subsequent years.

Old photos of “The Point”

The following picture looking up the road from the Point is undated but may have been taken in the late 19th or early 20th century. The two buildings in the foreground were built in the 19th century but all the other buildings that can be seen on up the road are from the 1770s. The roadway and paths along each side are probably pretty much as they were in the 1770s. Thus, the picture gives a sense of what the Point looked like at that time.

The above picture shows the view down Main Road toward the wharfs. It includes all of the houses built in the last three decades of the 18th century that are discussed in this paper starting with 2032 on the left or east side and 2033 on the right or west side of the road. The first two houses on the left, 2032 and 2034 were originally one-story capes like the second house on the right (2037), but had added two dormers on 2032 and a single dormer on 2034. The house at 2037 is the only one-story cape left without a dormer added to the front roof.

How the Original Buildings at the Point Have Survived for 240 Years

The original houses at the lower end of Westport Point that were built in the late 18th century have remained relatively unchanged since that time while the ebb and flow of economic forces and world events have swirled around them. Two of the original one-story Capes at 2032 and 2034 Main Road added dormers on the front-facing roofs to enlarge their second floors, but the facades of all the other 18th century houses remain pretty much as they were when built. It is interesting to trace the significant events that occurred over the past two centuries to note the impact they did have on this area and how some of the possible destructive impacts were avoided.

During the first 60 years of the 19th century, except for the two war years, 1812-1814, the whaling industry thrived in this area. New Bedford, “The City that Lit the World,” was the epicenter, but Westport Point was a thriving whaling port as well. Buildings at the tip of the Point such as the Cory chandlery and various boat yards serviced that industry and the Cory Store served as the Customs House for this harbor. Successful whaling captains built large houses up the laneway that still exist.

The last four decades of the 19th century saw the collapse of whaling as whale oil was replaced by kerosene and economic activity at the Point shifted more toward fishing. Buildings at the Point went largely unchanged as most of the inhabitants were too poor to do anything with them other than basic maintenance. Construction of a wooden bridge from the Point to the Horseneck area on the south side of the Westport River in 1893 helped to facilitate the movement of livestock out onto the marshes for grazing and some building of cottages on the beaches, but travel was still by horsepower up and down Main Road and not very impactful on the people or the prosperity of the Point. There is a famous picture of a herd of sheep being driven down the dirt road to the bridge and on to the salt marshes and grassy areas across the river. Note that the two houses at 2032 and 2034 were single story full capes with no dormers.

In the early 20th century, invention of motor vehicles as well as expansion of the textile industry in Fall River and New Bedford that was powered by electricity rather than water all had dramatic effects on Westport especially on its beaches that soon became crowded with summer houses, hotels and pavilions. Main Road and the bridge to Horseneck became the main conduit for thousands of visitors in the summers and the congestion on these narrow ways was a major problem. Despite the traffic, some of the old houses at the Point were rented out during the summer months to visiting tourists and a hotel built at the Point in 1889 also served these visitors.

All of this changed in the mid-20th century when three hurricanes in 1938, 1945 and 1954 ravaged this area. Many owners of the properties on the beaches, thinking that the 1938 hurricane was a once-in-a-lifetime or once-in-a-century event, restored their buildings soon thereafter, only to have them wiped out again by the subsequent hurricanes. Some of the houses at the Point were undoubtedly damaged but not destroyed. The most notable effect of the 1954 hurricane was that Laura’s Restaurant at the Town Landing, just south of the Cory Store, was washed away and floated up the East Branch.

After the third hurricane, the Massachusetts State Government decided to take action to prevent the construction of permanent buildings along the waterfront and instead provide public facilities in the form of a State Beach and State Campground as well as protected open space. While these measures saved the areas for public use, they also created the need for improved access so that the public could easily reach them. This led to the replacement of the old wooden bridge from the Point to the Horseneck with a modern bridge and the construction of a new highway, Route 88, from North Westport to the new bridge in the years 1957 to 1965. The new highway cut through some of the farm woodlots along the way, but it, together with the new bridge, greatly relieved the summer traffic congestion on Main Road at the Point and made the old properties along that road much more attractive to new owners.

Before those changes could lead to a rush of new buyers who might want to either greatly change and expand the old houses at the Point or even replace them with new mega-houses, the State provided a means for protecting such historic properties and buildings. It enacted two new laws: Chapter 40 that authorized municipalities to establish Historic Commissions and Chapter 40C that authorized the creation of Historic Districts.

In 1973, led by Westport historian, Richard Wertz, who owned the original Christopher Gifford house at 2002 Main Road, the oldest house on the Point, the Town of Westport adopted a by-law establishing the Westport Historical Commission and another by-law creating the Westport Point Historic District.

The Commission set out guidelines for making changes to the exteriors of the buildings within the Historic District and has since exercised its authority. The Commission’s work has gone a long way in protecting the historic structures within the Historic District and especially those structures discussed above that were built in the late decades of the 18th century.

The existence of the Commission and its powers put prospective buyers of properties within the Historic District on notice that they would be expected to conform to the guidelines when contemplating any future changes in the existing structures. This requirement has helped to attract buyers who appreciated the value and significance of the historic district and the property they were acquiring. Such buyers, in most cases, realized in advance that not only would their choices be limited, but also that they were making a commitment to the stewardship of the property that they were acquiring. The historic nature of the property and of the district in which it is situated probably tends to add to the value of that property. The responsibilities of future stewardship probably tend to reduce that value. Prospective property owners have had to make their own decisions as to how these two factors balance out.

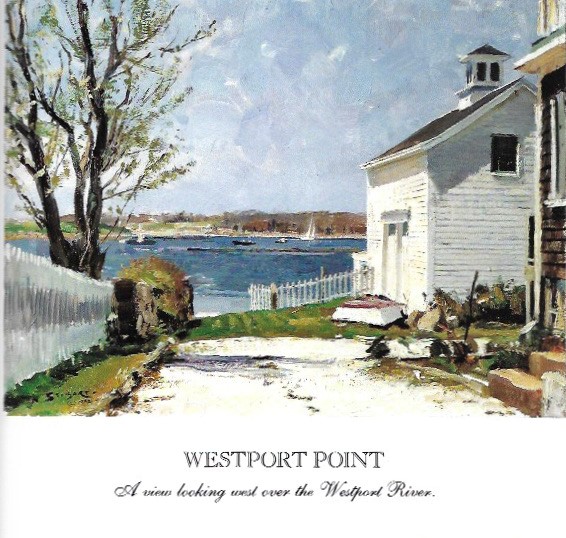

Now the main traffic down and up Main Road at the Point is from local residents or fishermen with boats docked at the end of the Point, or from pedestrians, dog-walkers and motorists who enjoy this historic community with its many well-preserved old houses and unobstructed views of the water on both sides of the peninsula. Many artists have come to Westport Point to try to capture the beauty of this place, perhaps none more successfully than the famous painter, John Stobart, who even settled in Westport and painted the image shown below in the 1990s. He described the scene and place as follows:

“The attraction of Westport Point to the artist is that its only street, Main Road, is lined with historic homes of great character, mostly finished in shingle or white clapboard. It is among the views between these homes, each looking out over the Westport River, that I found such an ideal subject to demonstrate simple perspective.”

From John Stobart, The Pleasures of Painting Outdoors. Boston, WorldScape Productions, 1993

[1] Leach, Sean. Westport Point 2020

[2] For an exciting discussion of “the Gaspee Affair” see James L. Nelson. George Washington’s Secret Navy: How the American Revolution Went to Sea. McGraw Hill: 2006.

[3] See Ellis, Leonard B. History of New Bedford and Its Vicinity, 1602-1892. Syracuse, NY. D. Mason & Co.: 1892.

[4] For information on American pirating see Patton, Robert H. Patriot pirates : the privateer war for freedom and fortune in the American Revolution. 2008.

[5] Compensation for this large tract consisted of: “thirty yards of cloth eight moose skins fifteen axes fifteen hoes fifteen pairs of breeches eight blankets two kittles a cloake 2 (yd) in Wampam eight paire of stokens eight paire of shoes an iron pot and ten shilling in another comodietie.” See Banks, Jeremy Dupertuis, Indian Deeds. New England Historical and Genealogical Society, 2002.

[6] Almy’s Tax Revolt was a refusal by three local citizens, Christopher Almy, Daniel Wilcox and Henry Head to pay a “minister tax” to support local Puritan/Congregational ministers. They submitted a petition to the Rhode Island Legislature to conduct a survey of the border as part of an effort to separate Tiverton and Little Compton from Massachusetts and annex them to Rhode Island. Almy escaped but Wilcox and Head were tried in Bristol, fined and jailed in Boston until their fines were paid. Wilcox escaped and fled to Portsmouth.

[7] The Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) inventory of historic assets in Westport can be accessed at the following website: <htttp://mhc.macris.net/>.

[8] Historian Richard Paull records that this property was transferred to “their assignees,” Brownell and Thompkins in 1829, then by them to Deborah (Bly) Barrows in 1835, and then by her to Jethro Howland in 1837. The 1829 and 1835 records may have reflected mortgages rather than transfers of ownership, which would be consistent with the MHC records.)