On the Road: Tracing the history, local lore and controversies of Westport’s highways, ancient ways, streets and corners

Posted on June 9, 2021 by Jenny ONeill

What are the origins of the names of our roads?

How did Sodom Road get its name?

How have roads developed and changed over time?

The 1831 map of Westport reveals a familiar network of roads, one that we recognize today, shaped by waterways, maritime and agricultural activities yet constrained by the two river crossings on the East Branch of the Westport River. In some cases, they follow established Native American trails, forming ancient links to modern cities of Newport, New Bedford, and beyond to the Cape. By the early 1700s, the outline of NS, EW routes was in place. The 1905 census records 31 streets, roads, and avenues. By 1948, the census records more than 90 roads and by 2002, Westport has more than 400 roads. The most significant disturbance to the established network of roads occurred in the mid-20thcentury with the construction of Route 88 and Route 195.

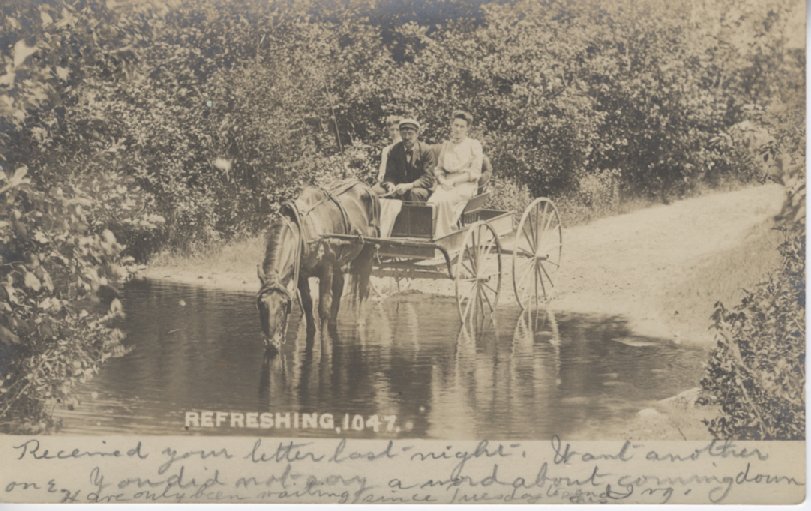

Today, as we drive along these roads, we follow the same routes taken by 18thcentury settlers and travelers. The speed at which we travel deprives us of so much intimate knowledge of our landscape. We speed by houses that were once taverns or stagecoach stops, passing wide spots in the road that were watering places for horses, scarcely noticing boundary markersthat were once reached at a slower pace by horse and wagon or by foot. Even with the coming of the automobile, travel remained comparatively slow. In 1910, the town set a maximum speed limit of 8 mph through the village and 15 mph in rural areas.

This research project is a collaborative effort. I am most grateful to the members of the Westport Historical Society’s Research Committee for their assistance, with special thanks to Richard Gifford, Kathryn Lamontagne, Sean Leach, Claude Ledoux, Maury May, and Robin Winters. Westport’s “old timers” provided many references for this project. Their memories and stories are preserved in videos of the Westport History Study Group (available via our website). Like many local history research projects, this is a work in-progress. Moreover, as much of the information has been derived from informal conversations, it is presented here with the understanding that there may be some errors in my interpretation.

Jenny O’Neill, Executive Director

2006.036.041

Horse-drawn wagon stopped at a brook – the horse is drinking. Man (identified as Abram Potter.

We invite you to share your own stories about your street and welcome your comments and corrections.

We have delved into the stories behind the naming of roads:

- Those named for landmarks that no longer exist, for example Hotel Hill or Bridge Street.

- Roads named for industries or businesses, such as Mouse Mill Road or Forge Road.

- Those named for prominent early English settlers such as Sanford, Cornell, Blossom, Howland, and Gifford families or for specific individuals such as Charlotte White or J. Douglas Borden. Some street names represent more recent Portuguese or French Canadian immigrants.

- Some roads derive their names from Native American place names such as Pine Hill Road and Horseneck Road.

- In more recent years, developers and their families selected street names, for example Christopher Circle.

- In some cases, the police and emergency 911 services required unique street names. Residents were asked to suggest street names.

Sources:

Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society

Old Dartmouth Highways Part A and Part B

https://www.dartmouthhas.org/colonial-era-records.html

Field notes of Benjamin Crane

MACRIS https://mhc-macris.net

The Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS) allows you to search the Massachusetts Historical Commission database for information on historic properties and areas in the Commonwealth.

Westport Town Historical Documents

https://www.westport-ma.com/historical-documents-and-oral-histories

Westport Historical Society collection

Westport Free Public Library History Room

Westport History Study Group June 2, 2005

Westport History Study Group, Glenda Broadbent May 4, 2006

Westport Town Records:

SOME GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON WESTPORT ROADS

by Richard Gifford

Many Westport roads are mentioned in the Dartmouth highways collection, with a good number being laid out in 1717/18. Roads tended to be of two varieties: “open ways” were laid out so as to be freely traveled, while “drift ways” were interrupted by “convenient gates for carts and horses” as they passed through the land of one owner to the next. There was no standard width for roads, but the most common widths were 4 rods (66 feet), 40 feet and 2 rods (33 feet). Some roads (Drift Road, for example) had different widths at different points.

Roads were all “laid out” (surveyed) and constructed by the town government, the Dartmouth Proprietors had no role in determining the course or width of the roads. However, the Proprietors did make an “allowance for a way” (i.e. an adjustment to the acreage calculation) when a highway traversed a parcel it distributed, sometimes even when the highway was no yet laid out but anticipated in the future.

The selectmen seemed to have acted as highway surveyors for the earliest roads, usually visiting the route in person. Not infrequently, after a road was constructed there were complaints about a road’s course, having proved inconvenient either to travelers or the abutting landowners, and the selectmen were generally receptive to such complaints, and would again visit the site and make adjustments to the courses of the roads.

In the early Dartmouth records, no roads are identified by any name we would recognize. Probably the earliest road name commonly appearing in deeds is “the Country Road,” which is Old County Road plus the western stretch of Rt 177. Even here, the early Dartmouth records do not use this name, but call it the highway from Stony Brook to Nokechuck bridge, the latter point being at the Head of Westport where the bridge crosses the river.

Where roads are referred to in deeds from the 1700s, the typical formulation is “the highway from Point A to Point B,” with the reference points being either a person’s house or homestead or some other landmark. This way or designating roads is problematic, as over time the owners of those homesteads changed, and there can be multiple persons with the same name. A brief example of this is the homestead of William Wood, which could refer to three different points named for three different people: 1) the intersection of Drift and Main Roads, 2) the intersection of Sodom and Adamsville Roads, and 2) the intersection of Charlotte White and Sodom Roads. (The last of these was the grandson of #2).

Even in the same time period, a road could be called by different names, because different lengths would be referred to or different labels applied to the same point. An example of this is Main Road in the early to mid 1700s. The south end is fairly simple, it would either be Peckecheck Point or some derivative, or Christopher Gifford’s (who owned all of Westport Point at the time). But I have seen references to the “to” point as various as —

“To Noquechuck Bridge” (thus including all of Main Road plus Old County Rd from Gifford’s Corner to the Head of Westport)

“To Benjamin Tripp’s” (i.e. the intersection of Main and Charlotte White Roads)

“To the Meeting House” (i.e. the Friends Meeting House at Central Village)

[after 1762] “To the Center Meeting House” [i.e. to Gifford’s Corner, as the “Center” Meeting House was located north of the high school]

“To Widow Howland’s” (i.e. Gifford’ Corner, as the Philip Howland house was, and is, on the NE corner of the intersection).

Corners

The 1800s mark the advent of naming “corners,” some still used as reference points in modern times. Some examples of named corners:

Brownell’s Corner: Intersection of Sanford Road and Rt 177, probably named for either Benjamin Brownell or his son Ezekiel, who both lived there.

Lawton’s Corner: Intersection of Sodom Road and Rt 177, probably named for George Lawton or one of his descendants, who lived there since the early 1700s.

Gifford’s Corner: Intersection of Main and Old County Roads, named for George H. Gifford, who lived there in the mid-1800s.

Macomber’s Corner: intersection of Sodom and Adamsville Roads, named for Alexander H. Macomber, who ca1850 built the house at 231 Adamsville Road.

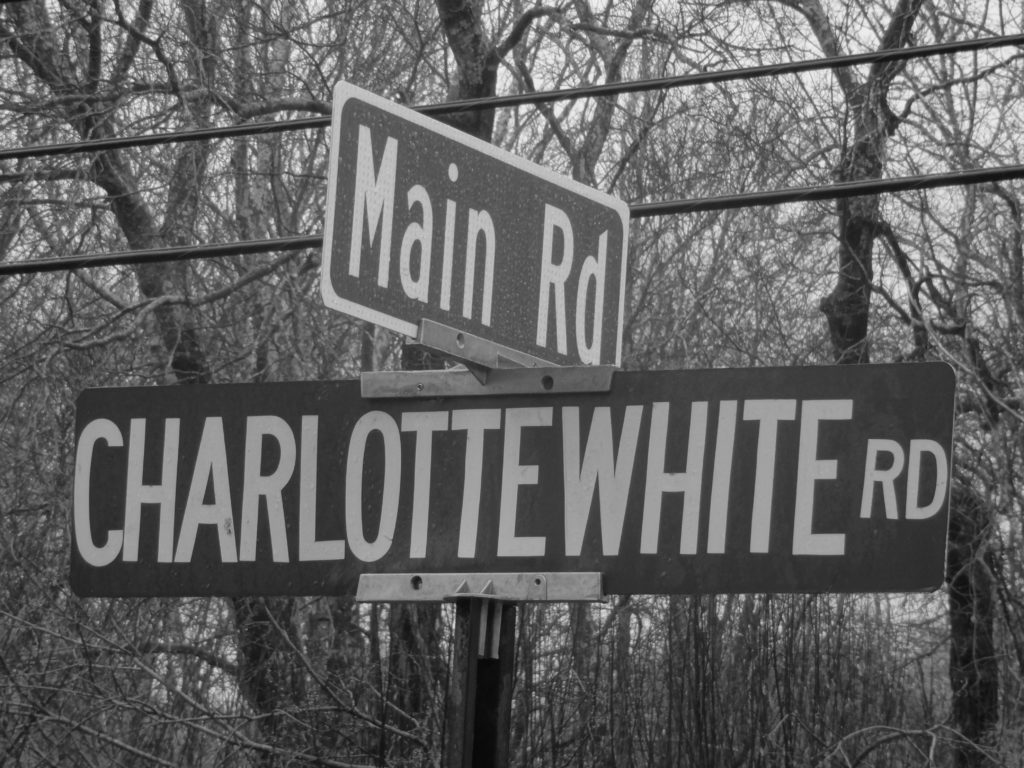

Kirby’s Corner: Intersection of Main and Charlotte White Roads, named for Tillinghast Kirby, who purchased the farm at the SW corner of this intersection in the 1870s.

Wood’s Corner: Intersection of Charlotte White and Sodom Roads, named for either George Wood, who lived in the house at 315 Sodom, or his father William Wood, the prior owner.

Booth’s Corner: Intersection of Main and Kirby Roads, named for the Booth family which lived at 679 Main Road in the mid-1800s.

Snell’s Corner: Intersection of Drift and Kirby Roads, named for Isaac Snell, who lived just north of this corner at 743 Drift Road. When Rt 88 was built, the eastern end of Kirby Road was closed off, so there is no longer an intersection here. When Justus Kirby owned this property in the early 1800s, the driftway was converted into a highway. Kirby’s well was situated in the middle of the road, but he refused to remove this navigational hazard. An accommodation was reached whereby the well remained, but Kirby provided a stone water trough for passing horses and oxen to be refreshed. In modern times the trough was moved to the front of the Grange, where it now serves as a planter.

The Evolution of the Highway Department during the 1900’s

At the turn of the century, Peleg S. Sanford Jr. was the single Highway Surveyor, with a $10,000 budget. The town roads were mostly narrow dirt wagon paths, except for some of the more heavily traveled North End roads such as Old Bedford Road. The road network essentially consisted of 4 major North-South arteries and 4 major East-West arteries. The single surveyor hired men to perform road work approved by the Town Meeting. A major repair in 1900 was Hix Bridge to the tune of $6,286. Modernizing of roads was already being done. This process, macadamizing, consisted of spreading crushed stone over the road bed and covering it with tar. The surveyor elections were on a yearly basis. The position see-sawed regularly. The surveyors had their supporters who would be hired if their man was elected, or replaced by new men if they lost the election. This practice continued until the early 60’s when Selectman Frank DeAndrade spearheaded employment tenure for Highway employees. A privilege later extended to other employees. An important part of highway maintenance was the crushing of the stone. Crushers were set up as near as possible to the work sites to minimize the cost of material transportation which was done by horse teams.

The 1912 report shows an expense of $58.00 for 29,000 pounds of coal. An indication of steam power usage most likely for crusher power. 14 horse teams were hired that year and approximately 70 men were paid for labor. One team of horses, man and cart earned $4.00 per day, roughly $60.00 in today’s dollars. There were 110 miles of road in 1915, compared to today’s 140 miles (State Highways not included). By 1920 the Highway Surveyor salary was $1825, there were nine roads being worked, the crusher plant was active, a tar account was maintained, snow bills were $3200 and the department purchased a Mack truck for $6500. 1933 saw the coming of the Public Works Administration which greatly accelerated road and drainage work, River dredging was also done, 171 men were employed that year. This WPA help lasted until 1942 when the war effort provided many jobs and the program was discontinued. By 1930 the department had permanent men and paid $5654 in wages. By the year 1940 the state provided aid to modernize roads. This aid is provided to the present and is known as Chapter 90 (Claude Ledoux, Westport in the 20th Century).

An A to Z of Westport’s Roads:

From Adamsville Road to Zulmiro Drive

Adamsville Road

“The road to the town house”

Adamsville Road is another road that shows evidence of an earlier course. In the dip between the two high points between Sodom Road and Adamsville RI, one can see a level (paved) stretch of road that reveals the earlier course. As one descends towards Adamsville one sees on the right a section of the road that is still in use. This older road then crosses the current road bed and descends on the south side of the road towards Joals Service Station. It then re-crosses the road, and its course can be seen to the north of the road just before the former Vincent De Paul Center. When the foliage is off the trees one can clearly see remnants of this road, including the bridge-like structure illustrated here (Bill Wyatt).

Taken from – “A Love Letter to Adamsville” by Bertrand L. Shurtleff

Providence Sunday Journal September 27, 1853

There are two stories about the origin of the name of our village. Characteristically, they are offered by the rival business clans. Marion (Gray) Hart, daughter of James Gray and sister of Herman, who operated the store for the third generation, had heard through her family that John Adams, second Pres. Of the United States, visited the home of Samuel Church, who built the Gray store in 1788. The home, now occupied by the Lloyd family, stands next to the Gray store. It was being built in 1815 during the Great Sept. Gale and part of the frame was blown down. She was told the village was name because of his visit.

Uncle Abe told me that he had another version of the naming from his great uncle, Eben Church. The land in the vicinity of the village was owned largely by Giffords, which gave the community the name of Giffordsville. But there were three mills then, all owned by the Tabers: the present gristmill, the carding mill up Crandall Road, which was in ruins in my boyhood, and a tanning mill just behind the small store now operated by Sylvia opposite where the paint shop stood. They and their friends called the village Taber’s mill.

The post office had been operated under the name of Little Compton since it was established in 1804. By the commons, the village in the center of the town, took over that name, which necessitated the choice of a definite name for our area.

Feeling ran high. Arguments around the stores held over and grew worse. Partisans of one faction hid behind stone walls and threw over-ripe eggs at ardent supporters of the other. Fists flew. Heads were cracked.

Eben Church, owner of the store now operating under the name of Abraham Manchester, decided there were unseemly goings on for a community where the Quakers faith vied with the Free Will Baptist. He accordingly tapped a keg of good Jamaica rum, then a common staple in the village store, and invited everybody of both factions to the store one evening to decide upon a name. When the dipper had passed several times and the powerful rum had warmed the cackles of every heart, Eben made this pitch.

“Gentlemen,” he said, his tongue in his cheek at having to use the term for some of his backward debaters. “We all knew that this year, 1847, we must decide upon a name for this village or lose our Post Office. We all know that two names have been suggested and supported. We all know that feeling runs high. If we call it Taber’s Mills, the Giffords and all their friends will be offended. If we name it Giffordsville, the Tabers will never forgive us, but we must have a name. The Post Office Dept. at Washington insists that we decide at once or get our mail delivered and post our letters clear over at the Commons five miles away.

“Now, I have gathered you together to suggest a compromise. Since half the village is bound to be disgruntled with either name, I suggest that we discard both and name it Adamsville for John Adams, the first President of the United States from New England.”

Amie’s Way

Named after Aime Lafrance, the founder of White’s of Westport, along with his wife, Rita.

Amory Pettey Lane

Bald Hill Road

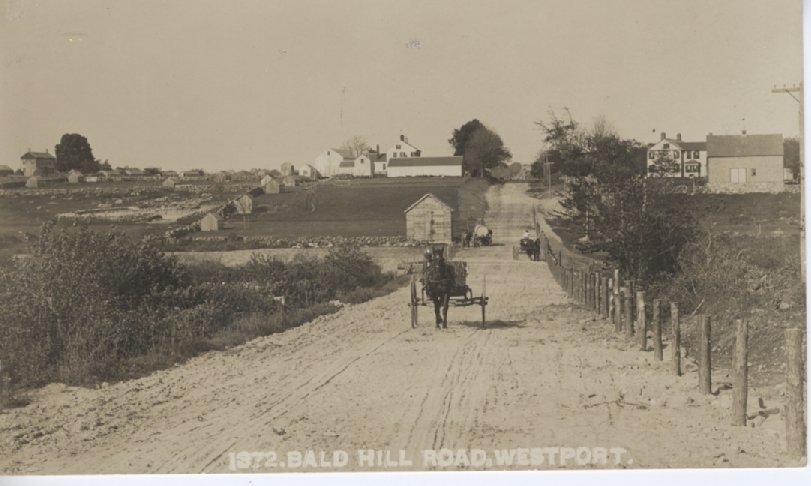

Horseneck Road from Russell’s Mills to Division Road was known as Bald Hill Road. As its name suggests this was a treeless high point in the landscape. In fact, Allens Neck Meeting House, once known as Bald Hill Meeting House, was a navigational landmark for sailors.

Beeden Road

Likely named for Richard B. Bedon (Beadon, Beeden, etc.) (b. Dartmouth 1797). He lived on the east (Dartmouth) side of the road about a half mile north of the intersection of Old Westport Road. He is shown on the 1852 map of Westport “R.B. Bedent” and contemporary Dartmouth maps. Beeden apparently moved to Martha’s Vineyard in the late 1850s, and the subsequent occupant of the house is shown on maps as “R. Dyer” [Reuben Dyer, Beeden’s son-in-law]. (Richard Gifford).

Beulah Road (see Gifford Road)

Blossom Road

This road is named after the Blossom family. The Blossom farm was one of the oldest and most prominent on the eastern shore of the North Watuppa. In 1911, the Watuppa Reservoir Commission dedicated the Blossom Farm to be the permanent headquarters for the maintenance and protection of its expanding watershed forest — the Watuppa Reservation.

The influence of the Blossom family can easily be recognized by the fact that both the road and the area are named for them. Elijah Blossom settled in the area when it was still considered to be part of what became Fall River. His son Eli Blossom was born in 1805. Eli Walter Blossom was born in January 1850. All three of these men participated in town government, were farmers and were considered to be valuable citizens.

A multi-talented person, Eli Walter Blossom also did some blacksmithing and some barbering. Until he was well into his 80s, he always attended town meeting. He served as surveyor of highways for Westport for more than a quarter of a century. In the history of the region written in 1899 it was said, “Mr. Blossom is one of Westport’s most successful farmers and enjoys the respect and confidence of a large circle of friends.”

Eli Walter Blossom was typical of the reliable and responsible farmers who played an important role in the history and development of Westport. He was linked by marriage and by heritage to families whose names are intertwined in Westport history. The house he built might be plain and simple with no distinguishing features for he was a plain and simple man; yet Eli Walter Blossom was, himself, a distinguished man of character (MACRIS).

Boathouse Row

Bojuma Lane

Bojuma Farm was named for Borden, June, and Mary.

B O R D E N and J Drives

This area was developed by J. Douglas Borden after whom the streets are named. “Dougie” Borden was a selectman in the 1950s. Some confusion can arise from the proximity of B Street to the south of B Drive.

Brayton Point Road

Bridge Street

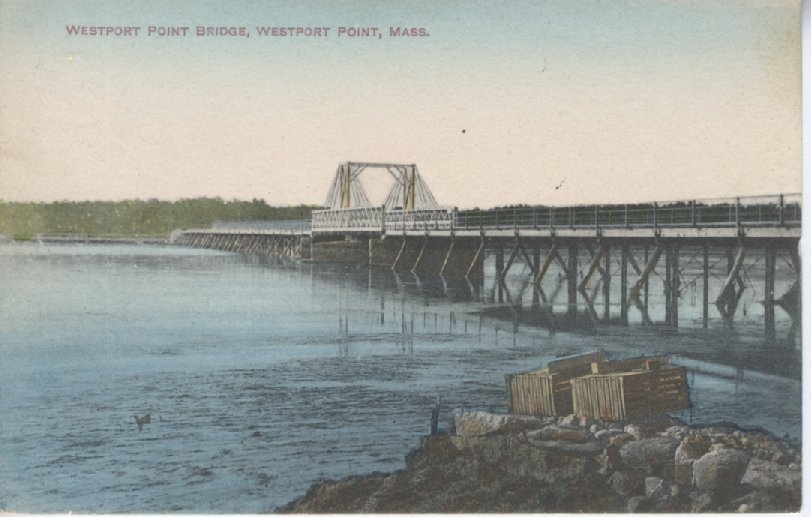

This road once connected Horseneck to the old Point Bridge. The Point Bridge was completed in 1894. As traffic jams plagued the Point and, with the construction of Route 88, the bridge was torn down in 1963.

Briggs Road

“The next daughter, Sarah Cook, married Arthur Hathaway and that brings us down the line to Albert B. Briggs, which would be my line. He was my grandfather and he lived here in Westport and his father was Christopher Briggs, who was the boat builder. He built the whaleboats – not the big, big boats. I could look up the dates when they came and lived here. In fact, Briggs Road – they lived, a ways down Briggs Road – and that was why it was named Briggs Road. Then I think one of the sons came down to where Christopher Briggs lived and built his boats.” (Interview with Janice Lawton Field).

Buttercup Lane and Holly Hill Ave

The Graham children voted for these two names because of the number of both plants on the location.

Cadmans Neck

This small promontory of land edging into the east branch of Westport River was once a hub of activity, a place where thousands of people would gather to participate in religious camp meetings. Given the specific logistical requirements for a successful camp meeting, Cadman’s Neck was a natural choice, offering good drinking water, pasturage for horses, shade for the audience, a forest to screen the meeting from the world, and access by water.

George Cadman was the son of William and Elizabeth Cadman of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. George Cadman settled in Dartmouth, Massachusetts by 1686, at which time he is believed to have possessed an 800-acre division of land, the amount granted to the original fifty-six proprietors who settled Dartmouth (then encompassing present day Westport, Dartmouth, New Bedford, Fairhaven, and Acushnet).

Though no deeds or documents identifying the exact quantity or boundaries of George Cadman’s initial land holdings are known, it is nearly certain that he received an 800 acre allotment when settling in Dartmouth. The closest documents approximating these are boundary descriptions in the field books of Benjamin Crane, the surveyor commissioned by the proprietors of Dartmouth to survey and record property boundaries throughout the settlement. Crane surveyed these lands between 1710 and 1721.

Cahoon’s Lane

Named for the Cahoon family who lived at this location.

Charlotte White Road

The typical pronunciation of the name Charlotte is “Shar-lot” but there is a local oral tradition that it was pronounced “Shar-lot-ee.” How did Charlotte herself pronounce her name? The first clue was found a few years ago when the late Bill Wyatt, former president of the Historical Society, was researching the 19th-century account books of the Westport physicians Eli and James Handy. Bill found an entry for “Charlotty White,” a phonetic spelling of her name that indicates a three-syllable pronunciation. The second clue was dug up a few months ago by Martha Guy as she combed the town records for information about early poor relief in Westport. Several town records from 1812-1813 refer to her as “Cholata” White, which drops the “r” (as most locals from Massachusetts and Rhode Island do) and flattens the “y” to an “ah,” but clearly shows the three-syllable form. Based on this evidence, it is most likely she was called “Sha-lot-ah.”

Charlotte White was born in 1774 or 1775, depending on the source. Her mother, Elizabeth White (1730-1827) was Native American – a Wampanoag, most likely from Martha’s Vineyard. Her father (whose dates are unknown) was a former slave variously referred to as Zip, Sip, Zilpiah, or Zephriah. He was apparently owned at one time by the Lawton family but worked for (or was sold to) the White family. It is likely that Zip was a slave when working for the Whites, because he took their name as his own, but that’s just a guess. Elizabeth and Zip married in 1765, and had a house on what is now Charlotte White Road. There is no record of any children other than Charlotte, and it appears that Charlotte did not marry; she is listed in one census as a “colored maiden.” Charlotte was connected to Westport’s well-known mariner, philanthropist, and black rights advocate Paul Cuffe (1759-1817). Like Cuffe, she had a Wampanoag mother and an African father who had been a slave. There are also numerous links between Charlotte and the Wainer family, who were in-laws and business partners of Paul Cuffe (Tony Connors).

Cape Bial

Derived its name from Abiel Macomber, a cordwainer, who is thought to have passed his days on the lane bearing his name. This lane was also known as Wild Goose Lane.

Chabot, Newton, Benoit

Possibly developed by Warren Messier in the late 1960s.

Cherry and Webb Lane

Cherry and Webb Conservation area is named after one-time owners George Cherry and Frederick Webb of the department store fame. George Cherry, owner of the Cherry and Webb department stores, built a house at 1280 Drift Road as a summer cottage in 1894.

Christopher Circle (and Patricia Way)

Named for two of the six children of George and Mary (Pelletier) Graham. They owned Holly Hill campground on Tickle Rd, too.

Cornell Road

Godfrey Cornell (1802-1891), founder and deacon of the Christian Church, Central Village, sixth generation to farm in Dartmouth, noted for successful management, and as a community leader. In March 1836 he bought a farm in Westport on Cornell Road and lived there thereafter. Cornell Road is named for him. The laneway at 58 Cornell Road may have been the principal road from Adamsville to Westport Point (MACRIS).

Cow Pie Lane

This lane probably derived its name from the cows that were omnipresent in the area (David Cole).

Cross Road

Once known as Skunk Alley, referring to the skunk cabbage that grew nearby (Cukie Macomber).

Davis Road

Named for the Davis family which lived in this area. It is not known when the first member of the Davis family came to Westport, but the intersection of Old Bedford Rd. and Davis Rd. has been known as “Abiel Davis’s corner” since at least 1798, when that phrase first appears in town records. Both Abiel Davis and Abiel Davis, Jr. are listed as heads-of households in the first US Census in 1790 (MACRIS).

Division Road

Drift Road

This road was originally a drift way, a common way, road, or path, for driving cattle. It follows an early North – South Native American trail. It passes through Snells Corner and Handy Four Corners. There are two granite bridges, Snell Creek Bridge and Kirby Bridge. Traces of the earlier road are easily seen just north of the intersection with the (new) Charlotte White Rd. Extension. There is a paved portion there that swings west while the current surface heads straight north; the stone walls follow that older section. More importantly the older bridge over Kirby Brook is now visible to sight and is well worth a look.

Between 1859-1865, a “civil war” was fought over the location of Drift Road. Conflicting layouts by the town and by the County resulted in two lawsuits to the State Supreme Court. (MACRIS)

Drift Road has been studied by the Massachusetts Historical Commission, and has been included in their survey of Massachusetts Heritage Landscapes. (Cf. Reading the Land, MA DEM, 2003 and the Inventory Form Continuation Sheet devoted to the road.)

In response to the news that Drift Road was to be paved, a local farmer retorted: “Huh, don’t know why they want to do that. ‘Taint nothin’ but a cow path!” (The Chimney Cupboard, Westport Public Library History Room Files).

Steve Chase standing next to the steam roller on Drift Road. “When I first knew it, the Main Road was a dirt road. When it was first macadamized, they had a steamroller going back and forth, and I used to ride on the steamroller. They’d harden it down by sprinkling it and then rolling it.” Mary Sowle

East Horseneck Road

According to Burney Gifford, East Horseneck Road is a recently applied name, created by Westport selectmen about 18 years ago after a tragic car accident. Unfortunately, the ambulance drivers could not find the location of the accident, leading the Westport police to rename the road. However, “it’s only East Horseneck Road if Westport is the center of the earth,” remarked Burney Gifford.

Fallon Drive

Rita (Fallon) LaFrance, the founder of White’s of Westport, developed this road.

Fontaine Bridge

Army Spc-4 Normand E. Fontaine died with three other soldiers in an ambush in Bien Hoa Province, in Vietnam, on May 8,1968. The Route 88 bridge was named in his honor in 1983.

Forge Road

A forge once stood at the confluence of Bread and Cheese Brook and the East Branch.

GIFFORD ROAD

For many years, Gifford Road was known as Beulah Road and associated with Beulah Grove Camp Meeting. In 1928, the town voted against changing the name to Gifford Road.

March 23, 1928

Mr. Frank R. Slocum

Dear Sir: I was not present at the annual town meeting, but am told that Article 38 assigning the names of the roads was adopted with the exception of the Gifford Road. Why this exception?

I do not think the vote could have expressed the real sentiment of the Town. It is a serious matter to change the name of a road that has been in general use for more than a hundred years. The exact date when the road was named I do not know, but it was named after my Great Great Grandfather, John Gifford who was born in 1754. In those early days he was one of the leading men of the town. It is my understanding that he owned the land on both sides of said road for about two thirds of its length. His land began with the old Levi Gifford farm (now owned by Charles Kirby of Fall River) and extended up past the State Road to Davis’s Corner. His land also extended east so it took in what is now Green Wood Park. To say the least, quite a few hundred acres. If any one man owned that property today, he would be the biggest tax payer in town. Presume he was the man that opened up and did the preliminary development in this section. I have in my possession one of his old deeds written more than one hundred and forty years ago. Would approximately fix the time when this road was named after him at near the end of the eighteenth century. Ever since that time we of this section of the town, for several generations, have been describing the land in our deeds as bounded by the Gifford Road. Now at this late date to call it by another name would cause unnecessary confusion in the records.

Tracing back the nick name (Sp) Beulah road to its origin, we find that sometime between 1880 and 1890, a short lived camp meeting association was located near the north end of the Gifford Road. These camp meeting association people named their camp meeting the Beulah Camp Meeting and as sort of an advertising scheme to advertise there meeting proposed that the road be called the Beulah road and that the nearest railroad station be called the Beulah station. Of course the New York, New Haven and Hartford promptly turned down the station naming schemers as presumptuous. Unfortunately a few thoughtless people caught up the expression Beulah road and have used it occasionally every since. The chief thing I remember about that ephemeral camp meeting is that like a bumble bee it was the biggest when it was first born. If one believes in that kind of advertising, possibly to have renamed the street Beulah road at that time might have helped the meetings; but to do it now, more than a generation after they have passed, would be very poor advertising.

There is no more occashion (Sp) for changing the name of the Gifford Road to Beulah than there was in Fall River for changing the name of the Stafford Road to Maplewood Avenue.

If the name Gifford Road should remain on the guide board, most people would forget all about the nickname in a little while. If the undesirable nickname of Beulah road should be put upon the guide board, it would tend to make new arrivals call the road by one name while the old families would be calling it by another.

Fortunately we have a grand old name, one that has been in general use for half a dozen generations, one that almost takes us back to early colonial times. Now when other towns and many historical societies are striving to preserve their old names as monuments of a worthy past, why should we destroy ours?

There is no more reason for changing the name of the Gifford road, that (than?) there is for changing the name of the Town of Westport.

Yours respectfully,

Charles Gifford Babcock,

Westport, Mass.

December 18, 1930

Since writing this letter, I have learned that it was my great great Grandfather John Gifford, who laid out this road from the grist mill at the Head of the River to Davis corner on the Old New Bedford road. This made a public road more than three miles long extending for the larger part of its length through his private estate.

Family tradition tells us that in those early times the Giffords were called the Land Kings of Westport. Aunt Nellie has told me that she can remember when there was a Gifford in every house except two, between this one and the State road, Those exceptions were William Slade’s and a Mr. Crapo’s.

Gifford Road by Richard Gifford

Gifford Road is supposedly named for my fourth great-grandfather, John Gifford (1754-1831). John’s grandfather, Stephen Gifford, moved from Horseneck Road to a part of what was then Tiverton in 1730, more precisely on the Fall River side of the Narrows approximately where the Kerr Mill complex later stood. John’s father Benjamin Gifford, a blacksmith, was a man of modest means but considerable progeny, as his obituary stated that he was survived by 128 children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In his 89 years of life, according to the obituary, Benjamin had never traveled more than 40 miles from home.

John Gifford followed his father in the blacksmith business and lived on Blossom Road north of the Watuppa Indian Reservation. An industrious and frugal man, he purchased numerous additional properties, mainly along Gifford Road, which he sold to his sons and others. Oddly enough, he probably never lived on the road named for him, as in the 1830 census he was still listed in Troy near Watuppa Reservation and his death the following year was recorded in Fall River.

The Westport historian Gladys Gifford Kirby, a descendant, related the story that John demanded payment of $400, representing a considerable sum around the year 1800, from each of his sons in order to get his permission to leave home. Many modern parents would probably be willing to pay much greater sums if it would induce their sons to leave, but with John it was the reverse, the amount arrived at through his precise calculation of what he was due for reimbursement for his expenses in raising them. I must admit I regarded this story with skepticism, until I came across the following advertisement published in the Columbian Courier (New Bedford), which shows how he dealt with his 19 year old son Peleg, who left home without paying:

NOTICE!

All persons are hereby forbid to trade, trust or transact business with PELEG GIFFORD, son of the subscriber, without the consent of him the said subscriber, and masters of vessels or others are forbid carrying him to sea without such consent being first obtained.

JOHN GIFFORD 2d

Westport, Nov. 12, 1802

The story of Gifford Road begins with John Gifford’s Westport property tax bill, which was for $6.00. Considering that at the time he owned over 400 acres of land in Westport, the bill does not seem unreasonable, but John declared that he wasn’t going to pay it, the town wouldn’t get a single dime from his purse. At the time Westport had a statute or ordinance which allowed taxpayers to “work off” their tax bills by working on the highways, at a rate of $1.50 per day for a man and a team of oxen. This probably was an artifact of Westport’s Quaker legacy, as the Town paid part of the expenses of maintaining the militia, and the more scrupulous of the Quakers objected to any connection to or support of military activity, whether direct or indirect. In John’s case religion was not a factor, as he had served in the Revolution, which would have gotten him disowned from any Quaker meeting that he might have been inclined to join, but the practice of working off the tax bill was open to all.

John yoked his ox team and started building a road at Abiel Davis’ corner, so the corner of Old Bedford and Davis Roads. Youngest son Weston, my third great-grandfather, was still living at home — apparently unable to raise $400 and afraid to skip out like brother Peleg and earn a blacklisting from his father — and was left to take care of the blacksmith shop on Blossom Road. The town was due four days of labor in lieu of taxes, but people noticed that John kept working week after week, then month after month, building the road southward. Naturally people were curious why, in effect, he was paying his tax bill many times over. When questioned, he responded that he was building a road so that he could visit his sons, and he wasn’t in the practice of not finishing what he started.

So southward he went, building the road past son Warren’s farm, then Luther’s, then Levi’s. The road was, by Westport standards of the time, remarkably straight from north to south. Straight, that is, until it reached the area of the Ferry farm, where the road makes a 90 degree turn to the east. The reason for the turn was that son Isaac’s farm was on the west side of the road at this point, while son Peleg’s place — Peleg was by then a ship captain and apparently reconciled with his father — was directly to Isaac’s east over towards Lawton’s mill pond. Peleg’s great-grandson, by the way, was Waldo Gifford Leland, an historian and archivist who was instrumental in founding the National Archives and was chairman of the advisory board of the National Park Service.

But back to the road, it was at Peleg’s that the road ended, at the corner near the Ferry farm and did not connect to Old County Road and the Head of Westport. Once again people were curious, and asked John why he stopped building the road without connecting it to Old County. John declared that he had no interest in going to the Head, and if others wanted to connect the road to the Head they would have to do it themselves, he had set out to make a road to visit his sons and his job was finished. And that is what happened, others had to complete it, for by then people had learned that once John Gifford had set his course, either for action or inaction, he was not a man to change direction.

Goodwater Street

Mr. Bonneau, (Bon Eau in French means “good water”) a developer, the go between of the farmers on Sanford Rd and those who wanted to buy lots on that section of the pond, post World War II. This is from Raymond Robillard (of Eastern Ave, then Narrows rowboat rental, then Plymouth Blvd). There may have been a mill along there at some point.

Greenwood Park

During the early part of the century up to the 1930’s, growth centered along the trolley line, now Route 6. The Greenwood Park area and other concentrations along Route 6 were largely developed on what was called coffee and tea lots. These were awarded as premiums upon presentation of coupons from the purchase of certain brands of tea and coffee (Claude Ledoux).

Half Mile In

A right of way to the river. It is double walled the whole way indicating that it was once an important road (Sean Leach).

Hix Bridge Road

Derives its name from the Hix family who ran the ferry across the East Branch and later built the bridge in 1738 replacing what may have been a chain ferry across the river. The bridge was considered by some to be “a common nuisance” as it obstructed the waterway between the Head and Westport Point.

Hix Bridge Road. “I remember before they widened Hix Bridge Road, I used to take my wheelbarrow and walk up Handy Hill, picking up tin cans and rubbish to try and discourage people from dropping more. And I could go all the way up and all the way down and there wouldn’t have been one car that would have seen me. The road just wasn’t used; they used Main Road, not much on Drift Road either, but more than on Handy Hill, I think. But anyway, there were wild grapes all over my path and I’d go up with my wheelbarrow. ” Eleanor Tripp.

Horseneck Road / Old Horseneck Road

The name Horseneck may be derived from the Native American designation “Hassanegk”, meaning “a house made of stone.” One such structure existed somewhere in the vicinity of the beach, described as an “old stone cellar, probably an excavation made in the hill side, lined with field stone and roofed over.” This structure was probably destroyed by coastal storms.

Is Horseneck Road in Westport or Dartmouth? It seems that no one really knows the answer. Several inconclusive responses have been received to date, including:

“It depends on who you ask and what time of day it is” and “It depends on where on the pavement you are standing.” According to Russ Hart, the selectmen are required to “perambulate the bounds” to verify the town boundary lines.

South section of Horseneck Road, also known as “the foot of the lane”

According to Ab Palmer, the south end of Horseneck Road was “more of a lane rather than a formal road, known as “the foot of the lane.” It demarcated the boundary between Westport and Dartmouth for fishermen. At that time, fishermen used large traps in the bay, and there was some friction between the two towns. Each town issued a permit to control access. The lane provided fisherman with a visual checkpoint so that they could determine whether they were in Dartmouth waters or Westport. “It was there for a purpose,” insisted Ab Palmer. “It kept us from squabbling with Dartmouth.” (Westport History Study Group June 2, 2005. https://vimeo.com/509294420).

Albert Lees: According to my grandfather, Albert E. Lees, the original Horseneck Road went south from Macomber’s Corner and then turned East at Bald Hill until it ended in Russell’s Mills. There was a laneway at the Bald Hill turn that went straight down to East Beach. This was a private way owned by the Almy’s. At the end of the lane, just before the right hand turn at the beach is a Westport Town Landing. (My grandfather was Landing Commissioner in the ‘30’s). At some point, and I am not sure when the Almy’s either gave the laneway to the town, they sold it to the town, or the town took it by eminent domain. In any case, it came under town control and was named Horseneck Road. This is the story I heard from my grandfather….

Hotel Hill

Hotel Westport once stood at the top of this hill. Built in 1897, it offered visitors modern conveniences such as electric bells, toilets with running water and excellent beds. The hotel was supplied with water from running springs. Most of the structure was destroyed by a fire in 1918. The foyer and meeting room survived. The structure is now a private residence.

HOWLAND ROAD by Richard Gifford

The story of Howland Road, in a sense, is a story of disputed land ownership that persisted for over two centuries. In the time immediately before King Philip’s War Acoaxet was ruled by the sachem Mamanuah, a young man barely out of his teens. His father, Tosonegin, had married as his second wife Awashonks, the squaw sachem of the Sakonnet tribe. This royal marriage had united, both in territory and government, the Acoaxet and Sakonnet tribes, similar to where the marriage of Ferdinand & Isabella had united the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile two centuries earlier to form modern Spain. But unlike the Spanish unification, the American version did not survive the death of the monarch, and after Tosonegin died Mamanuah claimed to be the true sachem instead of his stepmother, not only over the Acoaxets but also the Sakonnets. Beginning in 1673, Mamanuah sold to the Sakonnet Proprietors parts of his asserted realm, taking care at first to sell to the English only those parts of the kingdom which were inhabited by Awashonks and her people.

Awashonks, quite understandably, did not take kindly to this development. She had made her own land sales to the English, and regarded any proceeds from such sales as due to her alone, and did not appreciate Mamanuah selling from underneath her that part of her territory her tribe still occupied. Awashonks dispatched some her braves to kidnap Mamanuah in 1674; with “violent binding” they did “forcibly molest” him, these emissaries telling Mamanuah that if he knew what was good for him he would get out of the real estate business, pronto.

Mamanuah retaliated against his stepmother in the time honored, ancient tradition of his aboriginal ancestors: he filed a lawsuit against her claiming damages. Mamanuah demanded 500 pounds compensation, and walked out of court in Plymouth with an award of just five pounds in damages but with recognition by the Plymouth authorities of his legitimacy as sachem. He then proceeded to sell off, piece by piece, various parcels in Acoaxet. Some parcels were sold to the Sakonnet Proprietors, who were the only buyers authorized by Plymouth, some to other English settlers, and others to fellow tribesmen. In order to maximize his profits, Mamanuah would sell the same parcel to several different buyers.

Two of these sales, the first by Mamanuah and the second by his son, were to Daniel Wilcox. A son-in-law of Mayflower passenger John Cooke, Wilcox was fluent in the Wampanoag language, and acted as Col. Benjamin Church’s interpreter at his 1675 meeting with Awashonks at Treaty Rock in Little Compton, at which Church secured the queen’s promise of neutrality in the looming war. The second of these deeds, in 1693, stated that the land was conveyed to Wilcox in appreciation of the kindness and assistance he had given the tribe during King Philip’s War. This deed conveyed most of what was called at the time Stephen’s Neck or Newtinnick, the area between Quicksand and Cockeast Ponds.

Of course, in the eyes of Massachusetts Bay Colony, these deeds to Wilcox — a fugitive from justice at the time due to his insurrectionary activities —were literally not worth the paper they were written on, and the land was developed in accordance with the distributions from the Sakonnet Proprietors. Acoaxet was part of Little Compton until 1743, and it is worth noting that the Sakonnet Proprietors used a different system of land distribution from the hodgepodge, poorly devised method that was used by the Dartmouth Proprietors. Here, the area of Stephen’s Neck was distributed in large parcels, but the area of Barker’s Neck (called Curaest Neck or Kaukoiset by the Indians), the area east of Cockeast Pond, was neatly mapped out in relatively small 5 acre parcels. From roughly Cross Road north to Adamsville, the land was mapped out in 10 and 20 acre rectangles, arranged in three “tiers” which extended westward from the river past the present Little Compton boundary.

The area of Stephen’s Neck was, by about 1720, owned by various members of the Richmond family. In 1792 Thomas B. Richmond sold the area between Richmond and Cockeast Ponds to Sylvester Brownell, a veteran of Bunker Hill, and Brownell then sold it to Edward Manchester. In 1834 the 130 acre farm on both side of Howland Road was sold to William Howland (1775-1857) of Little Compton, and it is for this family that the road was to be named. Howland, who already owned two large farms in Little Compton, probably built the ca1840 farmhouse still in existence at 177 Howland Road.

Howland devised one of these farms to each of his three sons, and the Acoaxet farm was willed to his son Stephen Russell Howland (1816-1899). Stephen in turn gave this farm to his two sons. Asa Russell Howland (1845-1918), although in chronic poor health, had a farm which shipped produce for the New Bedford market. Asa’s brother Albert Franklyn Howland (1843-1907) inherited that part of the farm that was on the east side of the road. Franklyn Howland had gone to New York as a teenager to gain exposure to the world of commerce, but soon after his arrival the Civil War broke out. Although still underage, Franklyn Howland enlisted in the 14th NY militia, the “Brooklyn Chausseurs,” and fought at Bull Run. The repulse of the charge of the Chausseurs up Henry House Hill is where the Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson earned his famous nickname. Later Franklyn was transferred to Louisiana, where he was captured and endured lengthy imprisonment, including a stretch in the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond. Here he developed a serious illness that resulted in his partial paralysis for the rest of his life. Nonetheless, Franklyn was active upon returning from the war and moved to Acushnet, where he was a state senator and authored two books, a history of Acushnet and a genealogy of the Howland family, the latter still regarded as the standard reference for that family.

In 1883 Franklyn Howland sold his part of the homestead farm to his sister-in-law, Nancy Jane (Pearce) Howland (1849-1946). It was here that she erected and operated the Howland House hotel, an imposing Second Empire still standing at 214 Howland Road. At that time, the well-sited house had unimpeded views of the surrounding ponds and the ocean, and became a popular destination for summer tourists. Masquerade balls and garden parties were held for the guests’ entertainment.

But life was not to remain all garden parties in Acoaxet. Asa and Franklyn had a first cousin named Edward Wing Howland (1833-1903). Edward had inherited one of the farms in Little Compton owned by his grandfather, and conducted such a successful produce business that he expanded and purchased a half dozen other Little Compton farms. He was known as “the last Quaker;” many years after the other Quakers had died or stopped attending, Edward made the short walk from his house to Brimstone Hill each First Day for an hour of solitary contemplation in the Quaker Meeting House.

But Edward Howland, as he grew older, had eccentricities that grew increasingly bizarre, not to say deranged. On one of his trips to the Meeting House, the lifelong bachelor was accompanied by his housekeeper, who in an unlicensed ceremony performed by Edward himself and witnessed only by the ghosts of the departed, he convinced that they were now legally married.

But more pertinent to the story of Howland Road and vicinity, Edward asserted that as a descendant, he was the rightful heir of Daniel Wilcox, and under the 1693 deed to Wilcox from Mamanuah’s son he was now the rightful owner of Acoaxet. That meant, to him, that the existing residents were squatters who had no right to live there. Disdaining the traditional legal remedies of trespass, ejectment or quiet title,Howland seized upon a fourth method of removing the inhabitants not to be found in Blackstone’s Commentaries: arson. Henry Worth tells the story:

In 1897 Edward Howland of Little Compton, a descendant of Wilcox, became possessed with the idea that the title was valid, and as an heir he proceeded to enforce the claim against the residents of Coxet by destroying their buildings. This, however, was met with determined resistance, and Howland’s death quieted the strange demand. It seems beyond explanation that Howland should attempt to secure a claim that had remained dormant for over 200 years.

Huldah’s Way

Huldah’s Way is at the Point off Main Road. Huldah was the wife of Pardon Davis and they owned the farm at 1933 Main Road. There is also a creek there called Huldah’s Creek and Huldah’s Cove.

Hull Yard Lane (off Old County Road)

Although the name reflects the shipbuilding heritage of the Head, it is a more recent name dating from the 1980s (Sean Leach).

Hurricane Lane

Indian Town Road

The Fall River Indian Reservation is located here.

Jiggs Street

“Jiggs” is the nickname of Damase Giguere. The family already lived there before the road was named.

John Reed Road

According to Cukie Macomber, John Reed Road was extremely narrow with an exceptionally high crown. The identity of John Reed is a mystery. He may have been among the early proprietors of the Old Dartmouth region.

Judges’ Way

The following information was provided by Hugh Morton:

“We have a history of judges. My father was a judge in the Fall River Massachusetts District Court. My grandfather, James M. Morton, Jr. was a Federal judge in the First Circuit and my great grandfather, James M. Morton, was a member of the Massachusetts SJC, more formally known as the Supreme Judicial Court. When we created some lots at what we call Old House Farm, we needed a name for the laneway and Judges’ Way seemed appropriate.”

King’s / Queen’s Highway

Bob Maker provides the following information about this highway:

“In the earliest colonial days, just about everybody lived on or very close to the coast, and when they wanted to travel from place to place, they hopped into a small boat and sailed. Converting a Native American footpath into a road wide enough for wagons would have required an enormous amount of labor. Why bother when it was so easy to get around by boat, sticking very close to the coast. No big deal for a maritime people.

But there was one situation where this strategy failed. If you wanted to travel from the Plymouth area to Newport, going by boat would have meant sailing around Cape Cod, adding much time, distance, and danger to the trip. So colonists built the first major inland road in our region from Plymouth to Newport, and called it the King’s Highway (except for the period between 1702 and 1714, when it would have been known as the Queen’s Highway). There is a small section of road in the north end of New Bedford that is still known as King’s Highway.”

The highway includes Old County Road, Old Westport Road, the western section of 177, and Bulgarmarsh Road. Charles II of England ordered the road construction and between the years of 1673 and 1753, the road grew and eventually covered over 1300 miles from Boston to Charleston, South Carolina.

Lawton Lane

This area was dominated by the Lawton family, most of whom were engaged in agriculture.

Masquesatch Road

Mouse Mill Road

This road took the name of a mill on Mouse Mill pond. It was on the Ledoux property and ordered breached by the state in the late 1950s. According to Claude Ledoux, the name came from the story that the mill produced so little grain that it could hardly feed a mouse!

Narrow Avenue

Probably named because it is a narrow lane, rather than for any association with The Narrows to its north.

Old Bedford Road

The oldest way of traveling between Fall River and New Bedford, laid out sometime before 1825. In the 1880’s, in response to increased commercial exchange between the two cities, a new road was built between New Bedford and Fall River, known at first as New Bedford Road, later as State Road, now Route 6. The state took control of the road in the 1920s, considered a marvel in its day, it was in time surpassed by the super highway Route 195 (Carmen Maiocco).

Old County Road (Country Road) see also King’s Highway

A portion of the Newport-Plymouth trail was widened to meet the demands of traffic and given the name of Old County Road. Over this road in April 21 1775 rode the swift rider dispatched by Captain Kempton of New Bedford to carry news of the battles of Lexington and Concord to Newport and places along the route to order all minutemen to start for Boston immediately. Old County Road is part of the King’s Highway.

Perseverance Lane

Elliot Taber developed subdivisions in this location but faced many battles with the Planning Board. He decided to name it Perseverance Lane because of the many “roadblocks” he had to endure (Claude Ledoux). Another theory suggests that it may derive its name from connections to the Brightman family who lived in this location.

Pettey Heights

Pine Hill Road

Derives its name from the Native American place name “Peetskeshuet”, meaning pine hill. According to Sean Leach, the section known Old Pine Hill Road is, in fact, the newest part of Pine Hill Road, constructed to avoid the property owned by Wilcox, British sympathizer.

Jim Pierce described how Pine Hill Road ran to the east of his house at 722 Pine Hill Road, rather than on the west side. The road went over the brook where there was a place to water horses. He also mentions a road used by old timers known as the New Bedford Road which ran through his property. (Interview with Jim Pierce, Bicentennial interviews, 1976)

Popple Ridge

The upper portion of Drift Road at the Head of Westport was once known as Popple Ridge.

Reed Road

If you look at maps of Dartmouth from this period, there are a number of families named Reed living on Reed Road north of the Beeden Road intersection and south of Hixville. However, it is not clear for whom Reed Road was named. One possibility is Edwin Reed who lived at 118 Reed Road. Another possibility is William Reed, a Newport merchant, who purchased a 300-acre parcel at the south end of Reed Road. Originally Reed Road stopped at Forge Road, and only later continued up to Freetown (Richard Gifford).

Remington Avenue

Ridge Road

Informal cart ways, also referred to as ancient ways, connected farms and were used as convenient short cuts by locals. They are not generally marked on the published maps. According to Glenda Broadbent, Ridge Road (also referred to as Post Road) ran from Hix Bridge Road along the high ridge to the Point, mid-way between Route 88 and Main Road. A cross road ran from Main Road to Drift Road in the 1646 Main Road vicinity. The cellar hole of the Macomber house is still visible near the intersection. Russ Hart describes another “path of convenience” known as Bridge Pasture which ran from Cornell Road through the Brightman Farm to Half Mile In. These paths were used “only when necessary.” (Westport Public Library History Room Files).

River Road

This is one of Westport’s newer routes, it does not appear on the maps until 1895. Prior to that, there was no access to the west bank of the west branch.

Route 6 / State Road

In the 1880’s, in response to increased commercial exchange between the two cities, a new road was built between New Bedford and Fall River, known at first as New Bedford Road, later as State Road, now Route 6. It accommodated the Dartmouth Westport Electric Railroad. The state took control of the road in the 1920s, considered a marvel in its day, it was in time surpassed by the super highway Route 195. The state took control of the road in the 1920s (Maiocco).

Dartmouth-Westport Trolley. “I lived at the Point, and before we had a car, I never did see the other end of town. I used to go to Fall River once in a while with my father, and that’s about all. He used to start off about 7 o’clock in the morning, and after his shopping, get back about 5 o’clock. Most of the time, we went over the Gifford Road to the Head of Westport, then the old New Bedford Road (Route 177). I worked on that road. Route 6 was just a streetcar line; there was no road there. Old County Road through the Head was the East-West road through Newport to Cape Cod. A lot of people here who wanted to go into Fall River or New Bedford would take the stage. The mailman had a stage – started with horse and wagon, and then changed to cars. At Lincoln Park, they’d take the trolley. On the trolley, you could go to Newport, Bristol, Rhode Island, and Providence. The trolley line was at the bottom, and the cars would go up overhead.The Union Street Railway used to own Lincoln Park. At the north end of the parking lot at Lincoln Park, there used to be a car barn. When I was young, the only road that was tarred was the Main Road (David Rozinha).

Route 88

Constructed between 1956 to 1958, Route 88 had a profound impact on Westport, dividing farms, and disrupting the historic EW routes.

Claude Ledoux has studied the impact of Route 88 extensively (https://wpthistory.org/2019/10/a-history-of-westport-in-the-twentieth-century-by-claude-ledoux/). “Wood removal to clear the Route 88 construction way provided income for many. The trees had to be cut in four-foot lengths that were loaded on trucks and driven to the Anawan Pulpmill in East Providence. Here Mr. Brightman (founder of Brightman Sawmills operation) assigned where to stack the wood, sometimes in piles up to 12 feet high. Pay was by the ton weight, each ton six dollars cash after stacking. Weight in weight out. This involved cutting with 35-pound chainsaws, when combined with the handling of some pieces that weighted a couple of hundred pounds this caused “knuckles to drag the ground”, mine still are. No job was ever too hard after this.” (Claude Ledoux).

Route 195

Construction began in the early 1960s. By 1966, the stretch of road between the Braga Bridge to Route 88 Horseneck beach exit was open. A heated controversy raged about the need for an East exit ramp in the area of the Narrows. Originally the State had planned three exits: Fall River, Route 88 and Reed Road, but many in Westport disagreed, arguing that motorists would drive right by Westport. Town leaders lobbied politicians to add an additional exit. Selectman Al Dyson cornered VP Hubert Humphrey, asking him to look into the matter. By 1966 the State approved the exit ramp at Sanford Road, construction of the ramp began in 1968 (Carmen Maiocco).

However, even today, there is no directional sign to Westport on Route 195.

Route 177/American Legion Highway/Bulgarmarsh Road

This was a major corridor of settlement during the 19th century. Rte. 177 follows the old course of Rhode Island Way, a road originally an Indian trail that led from Howlands Ferry in Tiverton to New Bedford. The road is more or less straight now, but if one goes to Tiverton, one will see Old Bulgurmarsh Road, a section that branches off to the north from the current road. Elsewhere along the road one can determine an older course by the stone walls that once lined the road but now sit some distance back from it (Bill Wyatt).

Newspaper article HISTORY OF ROUTE 177

“No!” shouted many Westport protesters at a Town Meeting in 1947. “We want no part in Tiverton’s name for the road.” One section of the road is very new, the other partly very old. But… “Those who live and will build along the new part of this road need an address,” someone else declared. Mr. Morton reminded the voters that it was “very unwise” to change the names of roads due to legalities of property deeds. Another person declared that the “State would probably name it anyway if they were going to take it over.”

Old County Road runs through the Head, westward to where Main Road joins it, there it turns north and continues to RT. 177, where it again turns westward to the Tiverton line. There it becomes known Bulgarmarsh Road. And…This is what Tiverton would like the complete road to be called, including the new road that was cut through to Route 6. One last suggestion was received, that was, to call this new part “New County Road.” Checking with the Westport Highway Department today, none of the names above won out. The State did take the road over. It is now called the American Legion Highway. Or if you prefer the ‘old standby’ Route 177.”

Sanford Road

The Sanford family was an important family in the history of Westport, and much of the northern region of the town, east of South Watuppa Pond, was Sanford farmland. Peleg S. Sanford Sr. who was born in Westport in 1810, owned land along this road. His son Daniel, born in 1833, lived the typical life of a Westport farmer in his family home. He and his wife Patience Lawton Sanford were married in 1855 and had at least three children. Daniel was to leave Westport at the age of 30 when he, along with his brother Barnabas, enlisted in Company B Massachusetts 3rd Heavy Artillery Regiment. This group was originally formed to protect the Massachusetts coast line, but was sent in 1864 to reinforce the garrisons guarding Washington D. C. Daniel was promoted to Full Artificer, which meant he was in charge of maintenance of the military equipment. Daniel returned to his family home where he lived until his death in 1911 (MACRIS).

View looking south from Sanford Road. Photograph taken Monday September 8, 1924, 10.00 AM at Brownells Corner (South end of Sanford Road) Westport Mass. Time of accident, 8.45 PM Sunday September 7, 1924. A cole towing car mass registration 65626 operated by Edward ? 177 Roothland Street,Fall River Mass. His companion Germaine Blair age 22, 68 Barrett St. Fall River, Mass was killed.

Scotch Pine Lane

Janet Gillespie provides a firsthand account of the origins of this name in her book “With a Merry Heart.”

“Baba, my grandmother, believed in celebrating anniversaries with some significant act, and on my first birthday she set out one hundred little trees to mark the event. They were Scotch pines because of our Scottish heritage and, as Baba often said, we would always remember that year because of me – her first grandchild. The road was called Scotch Pine Lane after this. In that era it ran from the main road up over the top of our hill and down the other side to the shore of the West River, a distance of about half a mile. It was a dirt road with a strip of grass down the middle where Gyp, the family horse, left hoof marks and piles of manure.”

Sisson Farm Lane

Richard Sisson settled at the Head of Westport in 1671.

Small’s Village / 1st, 2nd, 3rd Street

Reuben Small, a local farmer, developed this area. After the hurricane of 1956, many beach-front cottages were relocated to these three streets.

Sodom Road by Richard Gifford

In its early days, Sodom Road was populated with some of the most significant religious figures in the history of Old Dartmouth. By the end of the 1800s its modern name — with its connotation of moral depravity — had become firmly attached to it. What event or people were behind the naming of Sodom Road?

Old Dartmouth highway records show that Sodom Road was laid out by 1718. The earliest section to be surveyed was its southern stretch between its intersections with Adamsville Road and Narrow Avenue. In the early 1700s, the dominant landowners on the west side of the southerly part of this stretch were George Wood and his son William, the east side was owned by various Potters. From the 90 degree turn in the road in the area of Weatherlow Farm northward to the Narrow Avenue intersection, the Davis family owned most of the land on the east side of the road and the Cory, Soule and Taber families on the west side. Aaron Davis (d.1713), whose 1690 homestead was at the corner, was one of two early ministers of what we now know as the Old Stone Baptist Church in Adamsville.

In 1698 the Town of Dartmouth was indicted by the Boston authorities for failing to hire and maintain a Puritan/Congregational minister, as the law required. The Dartmouth selectmen — George Cadman and Jonathan Delano — responded that there was no violation, Dartmouth already had two ministers, namely Aaron Davis and Hugh Mosher. The court was not amused by the selectmen’s response. These two Baptists were not only not proper ministers, in the eyes of the court, it was questionable whether they could even be considered Christians. This was the initial skirmish in a conflict between Dartmouth and Boston that was to last for decades, and to result in the imprisonment of a number of Dartmouth selectmen.

At the east side of the intersection of Narrow Avenue and Sodom Road was the farm of Joseph Mosher, son of the other early minister of the Baptist Church, Hugh Mosher. On the opposing west corner was the homestead of Jonathan Taber. Jonathan’s father, “Elder” Philip Taber (1676-1751) was the stepson of Aaron Davis and successor to Davis and Mosher as lay minister of the local Baptists. His sister Lydia was the wife of Joseph Mosher, and Philip’s own wife Margaret was the daughter of William Wood who lived at the south end of Sodom Road. Grandson of Mayflower passenger John Cooke, Taber was the owner of the grist and saw mill in Adamsville on the site where Gray’s Grist Mill now stands, probably built ca1715. By the time of death Philip Taber was perhaps the largest landowner in what is now Westport, his land stretching from Adamsville north along the Tiverton boundary to between Sawdy and Devol’s Ponds, interrupted only by the holdings of his brother John Taber. While serving as a selectman of Dartmouth, according to Henry Worth, Philip Taber was imprisoned for 18 months for refusing to collect the “minister tax.”

The next section of Sodom Road to be laid out was the middle section, between the intersections of Narrow Avenue and Charlotte White Road. This section was dominated in the early 1700s by Hugh Mosher and his sons on the east side and the Devol family on the west side. Hugh Mosher came here from Newport and had a lot of money to purchase land: in addition to several farms along Sodom Road he owned land on both sides of Horseneck Road stretching from Akin’s Corner south to the sea, much of which he sold in the early 1700s to Job Almy, and from the same corner eastward about half a mile to the area of the Allen’s Neck Meeting House, which he sold to son Nicholas Mosher and son-in-law Peter Lee. Hugh’s first wife, Rebecca Maxson, was an infant survivor of the 1643 Indian massacre in the Bronx in which her father and brother were killed along with their spiritual leader Ann Hutchinson. The Devols were another family that came here from Newport, where their progenitor William Devol was a member of Rev. John Clarke’s Baptist church. The Devols, and the Moshers to a lesser extent, gravitated quickly towards an association with the Quakers.

The north stretch of Sodom Road, from the Charlotte White Road intersection north to the intersection of Rt 177, was dominated by the Devols, Moshers and at the north end by George Lawton and his descendants. Lawton purchased his large homestead in 1701 and came from Portsmouth, where he apparently had learned the skill of building mills. He erected a sawmill on the west side of the river at the Head of Westport soon after his arrival.

Given the deeply religious nature of the early residents of Sodom Road, why did the road itself acquire a name that represents moral depravity? The answer, according to the historian Henry Worth, can be found in the mid-1800s. There was a certain farm on Sodom Road that

. . .had a notorious reputation. It had been owned by the Cory and Davis families and in 1832 Edmund Davis sold it to Stephen Peckham. In 1840 the representative of the Peckham estate sold it to Abner D. Tripp. In 1875 John G. Tripp conveyed it to Nathaniel Kirby. During the ownership of Peckham and A. D. Tripp the occupants of this place kept a resort of such character that it was called the Sodom Place. From this circumstance the road had since been known as the Sodom Road.

Exactly what vices were indulged in at the Sodom Place Worth leaves to our imagination. Stephen Peckham, the first owner of the Sodom Place, spent most of his later life in New Bedford, where in several directories he is listed as a gardener. The second owner of the Sodom Place, Abner D. Tripp (1807-1895) also leaves no clue to the nature of the notorious activities in the census or vital records. From all appearances in those sources he was an ordinary farmer, in 1860 farming 18 acres while owning 37 acres of unimproved land, owning one horse, two cows, four “other cattle,” three sheep and one pig.

Abner did leave behind a surviving house built ca1850 at 790 Sodom Road, but from Worth’s description and the deed evidence this small house lot was not the location of the Sodom Place, which would have been a 30 acre farm on the west side of Sodom Road a short distance north of the house. There does not appear to be any surviving buildings from that era at the location of the Sodom Place. Abner married Almira (Devol) Davis, widow of Abraham Davis and a sister of Westport folk artist Ruby Devol Finch. Almira, together with her daughter and granddaughter, are buried in the “Tripp-Taber” cemetery south of the surviving house at 790 Sodom. The proximity of this dilapidated and overgrown cemetery to the site where Aaron Davis would have built his house ca1690 leads me to think that it may be the site of the Davis family cemetery, which is shown occupying a fairly large area on the 1895 map of Westport. Certainly the property was owned by Davises or their descendants for over two centuries, lastly in the late 1800s by Gilbert Macomber Jr., whose mother was a Davis sister of Almira’s first husband Abraham (Gilbert Jr was the great-great grandfather of “Cukie” Macomber).

As an addendum, we include an unlikely version of the Sodom Road story as recounted in the New Bedford Standard Times, January 24, 1981. These details are unconfirmed by written sources. It is worth noting that Sodom Roads located in other towns, are generally associated with taverns and with the availability of alcohol:

“Was there a realtor some time back with a cruel sense of humor? Or was the name prompted by some marsh with a sulfurous odor of swamp gas? Sulfur made up much of the fire and brimstone the Bible says destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah and several licentious communities. The surprising and most likely explanation comes from a spicy chapter in local lore: Sodom Road drew its name from Quaker disapproval of past times at two houses in that neighborhood called “Sodom” and “Gomorrah.” “They were two establishments of some kind,” said Attorney Richard Paull. Housing authority member Mary L. Medeiros remembers hearing stories from old timers that Sodom and Gomorrah sheltered a certain kind of lady.

“I don’t know that they were that,” Paull said. “But whatever they were, the two houses caused the eyebrows of some sedate Quakers to be raised.”

He heard the story from Edward L. Macomber, town clerk from 1898m until his death in 1951. Macomber was told the tale by his father, town clerk from 1850 to 1898.

Paull said the dens of iniquity probably stood in the late 19th century. “Unlike the city, I really don’t think these establishments would be permitted in Westport.” Residents of the houses took to feuding, Mrs. Medeiros said, and either Sodom burned down Gomorrah or the other way round. The exact site is uncertain but supposedly a cluster of lilacs marks the spot.

Souza Lane

Developed by Fran and Joe Souza. Fran was a longtime town bus driver for school children in the 1980s.

Thanksgiving Lane

There is some controversy over the location of Thanksgiving Lane. Gladys Gifford Kirby, Katherine Hall and Mary Sowle, all reliable local historians of the 20th century, declared that Thanksgiving Lane went to 2031 Main Road, the old residence of William Watkins. Christiana Allen, former resident, called it Thanksgiving Lane “as she was a religious woman who continually gave thanks.” (Westport Public Library History Room Files).

Tickle Road

Tickle Farm is located between Route 177 and Watuppa Pond. Tickle Store in Swansea is related to the same family.

Turtle Rock Lane

Valentine Lane, Westport Point

New York banker William Valentine built a stunning Second Empire house with Italianate features in 1870. The lane is located alongside the house at 1991 Main Road.

White Oak Run

Is White Oak Run in Westport or Dartmouth? The following article was found in the files at the Westport Public Library History Room:

“The Town of Westport has discovered a road that has been part of the town for more than a century. The discovery was made in the course of a trial in New Bedford Superior Court today. White Oak Run considered to be part of Dartmouth for over 100 years, actually is well inside the eastern boundary of Westport. This was brought out by selectman Carlton Lees of Westport today in testimony before Judge James Bento. Lees was called on for testimony in the appeal of David Sherman of New Bedford, who was charged by Dartmouth police with operating while under the influence on White Oak Run Road … Lees told the court that a search of the area and records dating back to the 18th century showed the true ownership of the road. Despite this Judge Bento denied a motion …for a directed verdict in the case.” (Newspaper clipping undated, Westport Public Library History Room Files).

Zulmiro Drive

The influence of local Portuguese families is represented by this street. Zulmiro was the first name of State Senator Mike Rodrigues’s grandfather who developed that parcel. He also owned a large portion of Route 6.