Two Rivers of Resistance

Posted on December 6, 2024 by Jenny ONeill

Two Rivers of Resistance

By David C. Cole[1]

During the Revolutionary War the South Coasts of Massachusetts and Rhode Island were largely controlled by the British Navy which had local headquarters in Newport and patrolled the length of Buzzards Bay. The British assault on Dartmouth in September 1778, that included raids on settlements and harbors from Acushnet to Padanaram, devastated those areas and demonstrated their vulnerability.

Snuggled in between the Sakonnet River and Padanaram Harbor were two smaller rivers over which the British were never able to achieve dominance. Those rivers – the Westport or Acoaxet River and the Slocums or Paskamansett River – continued to serve as safe havens for private ships including privateers who harassed both the British Navy and British supply ships and smaller craft that carried supplies to Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard.

The Westport River, then called the Acoaxet, provided natural protection against large British naval vessels because of its narrow entry channel that required ships to make a U-turn in a narrow shallow passage between two shores that offered excellent sites for sharpshooters who could pick off any seaman on deck. Therefore big, deep draft square-rigged ships could not manage that passage. In fact, there is no record of any British naval vessel ever entering the Westport Harbor during the war. There are legends that some British naval ships lobbed cannon balls into what is now known as Westport Harbor, but none ever sailed through the channel into the harbor.

The Village of Westport Point came into existence in the 1770s as people from nearby towns in Rhode Island that fronted on the Sakonnet River – Tiverton and Little Compton – moved their ships, shops and homes to Westport Point to be out of range from British harassment and capture. Docks, boat yards and ten residences were built at the Point in that decade on what had previously been pastureland.[2]

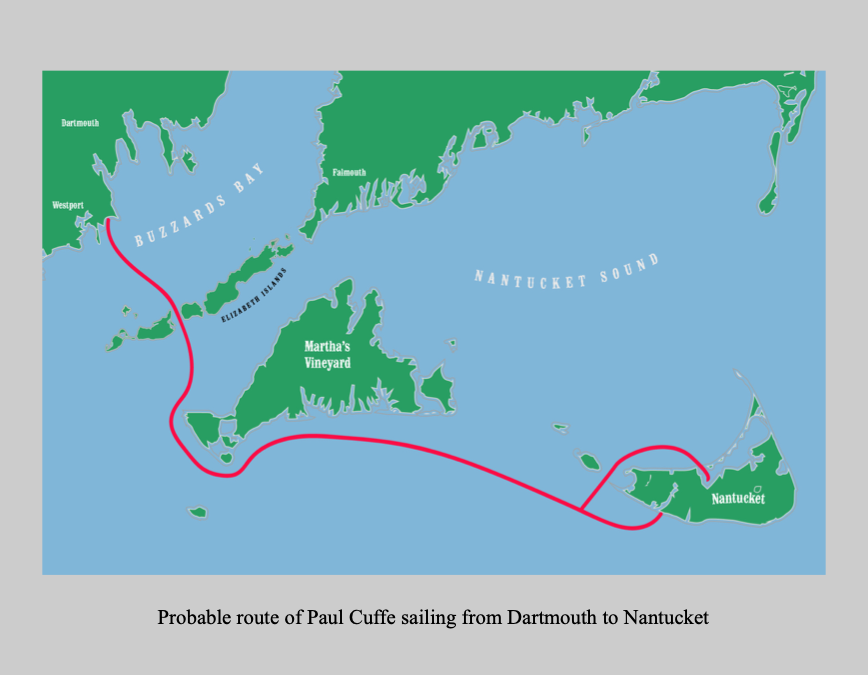

The Slocums or Paskamansett River had a very different configuration and played a different role. It was relatively shallow and impossible for larger ships to enter. But it provided a safe channel for smaller sailing vessels such as shallops or small sloops to sail upstream to the area around Russells Mills, load up with supplies and sail back out on moonless nights to proceed, undetected by British or privateer ships, and deliver supplies to Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Nantucket especially had a largely Quaker population, many of whom were opposed to war and therefore sought to remain neutral in the battle raging around them. The British sought to blockade them and disrupt their supply chains. The area around Russells Mills was also heavily populated by Quakers who were probably supportive of their friends on Nantucket.

A most notable person who set out to penetrate this blockade was Paul Cuffe, a mixed African/Indigenous resident of Dartmouth who, in his teens had sailed on three whaling voyages and, on the last one in 1776, been captured by a British naval ship and imprisoned in a prison-ship in Brooklyn for three months. Paul Cuffe had probably become acquainted with whaling ship owners from Nantucket during those times and also became aware of the supply shortages the people of Nantucket were facing. After being released from the naval prison in New York in the fall of 1776, it seems reasonable to believe that Paul may have joined forces with his Indigenous brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, who had just moved in and set up a tannery business at Russells Mills. They may have been able to borrow a small sailing craft (probably a shallop that was not being utilized because of the war) and launch the Nantucket supply run. Shallops were popular vessels for such operations because of their reliance on leeboards rather than keels to make headway when sailing into the wind. Leeboards could easily be raised when entering shallow waters or running up on shores which helped them both to escape pursuing vessels and to deliver supplies to island residents.[3]

The activities in these two rivers – the Westport (Acoaxet) and Slocums – although not extensively recorded, provide important examples of resistance to British efforts to dominate and defeat the American colonists. This Slocum River to Nantucket supply run was carried out by persons of African and Indigenous origin. Both the refuge provided by the Westport River and the ability to run the blockades are examples of successful resistance and circumvention of British rule that were successful in serving American over British objectives.

Hypotheses Relating to the Wartime Roles of the Two Rivers

In developing our narrative about the possible roles of the Westport and Slocums Rivers in the Revolutionary War, there are very few specific references in the historic records or literature. Consequently, we have had to rely upon a number of hypotheses or informed guesses about what probably happened. We will here set out the main hypotheses that undergird our narrative.

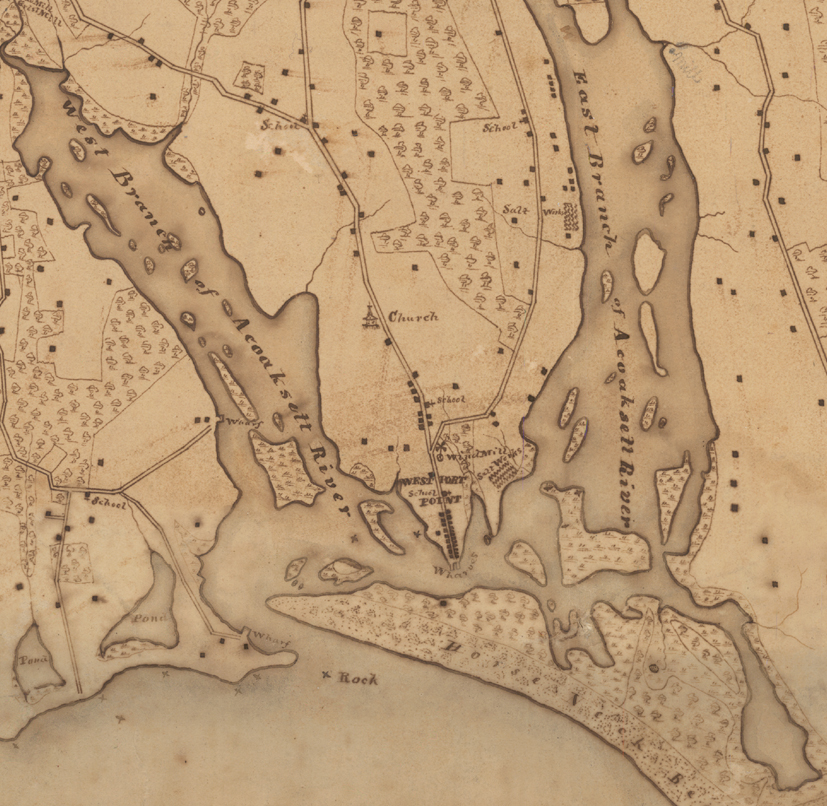

For the Westport River, the unique configuration of the river mouth that would have made it so difficult and dangerous for sizeable naval ships of that time to navigate is the primary factor in hypothesizing that it provided a safe refuge for ships seeking to stay clear of British Naval vessels. As shown in the image below, the mouth of the river was very narrow, passing between two banks that offered favorable positions for defenders to fire upon any unwanted enemy ships. Also, the only favorable wind for a square-rigger would be from the southeast, but after passing the mouth, the ship would have had to turn sharply directly into the wind.

The following quote from a report of the Public Archaeology Laboratory supports this:

“Westport Point was active during the Revolutionary War as one of the safest, most-protected harbors in the region. The high dunes at Horseneck Beach blocked the Point from view and the rocks and ledges in the harbor made navigation difficult to outsiders. At least one American vessel, the Union, was docked at Westport Point (Smith et al. 1976:8). The British referred to Westport Harbor as “the devil’s pocket hole,” a clear indication of its highly defensible position (Hall and Sowle 1914:21). Although British ships could not enter the harbor, there is some documentation that they shelled the Point from outside the dunes on at least one occasion (Ford 2022).”

It is not surprising that there are no records of British naval ships attempting such an entry into the Westport Harbor and only some vague reports of such ships sitting out in open water and lobbing cannonballs over the dunes into the small village at the Point.

Although there are not many records of Privateers being based in the Westport harbor/estuary area, it seems likely that privateering ships from Westport and other South Coastal communities sought refuge in this harbor either to escape pursuit by enemy vessels or just to have a safe place to rest up for a while and take on supplies from the surrounding farms. Present day experience confirms that this large estuary could have held many ships especially when there was no bridge to Horseneck Beach that cut off much of the East Branch of the River.

The Privateers probably did not try to bring their prizes into this Acoaxet refuge but rather took them to places like New Bedford where there was easy access, ample dock space and storage facilities into which to offload their cargo. It was the large number of prize ships and offloaded cargo that inspired the massive British raid into Clark’s Cove and the greater New Bedford area on September 6th, 1778 that destroyed many ships, warehouses, offices and residences.

Specific reference to privateers out of Acoaxet from this time include the following:

- Swallow – a privateer sloop out of Rhode Island, owner John Innis Clark of Providence.

- Two captains from the Head of Westport – Captain Peleg Peckham and Captain John Gifford – were also reportedly engaged in privateering, possibly out of Acoaxet.

For the Slocums River the evidence is also more circumstantial than specifically documented. We put together statements by two persons who were either directly involved at the time, or recorded stories of persons who were involved, to depict the situation, and then add our own observations based on experience of the circumstances today.

We begin with an excerpt from a Memorandum written many years later by William Rotch, Sr. a prominent Nantucket businessman, that describes the situation on Nantucket during the Revolutionary War:

“It was about the year 1778 when the current in the country was very strong against us…. The vessels we sent after provisions came back empty, and great suffering for want of food was likely to take place. The people who thought we ought to have joined in the War (not Friends) began to chide and murmur against me. They considered me the principal cause that we did not unite in the War, (which I knew was immeasurably the case), when we might have been plentifully supplied, but were now likely to starve; little considering that if we had taken part, there was nothing but supernatural aid that could have prevented our destruction.”[4]

Next, we add a statement from Daniel Ricketson’s History of New Bedford[5] written in 1858, that describes Paul Cuffe’s activities during this same period:

“At the age of twenty, Paul, in company with another brother of his, David, built a boat. They were to navigate her together; but it then being war time, and his brother having never been at sea, after having proceeded a part of the way on their voyage to Connecticut became so much alarmed for their safety that Paul was obliged to return with him. Soon after this Paul undertook a trip to Nantucket with a boat-load of produce, but in crossing Buzzard’s Bay was seized by “refugee pirates,” who robbed him of his boat and cargo. Nothing daunted, in connection with his brother, before mentioned, they built another boat; and having procured a cargo upon his credit, Paul again started for Nantucket, and was again chased by pirates: but night coming, he escaped from them, but ran his boat upon a rock on one of the Elizabeth Islands, and so badly injured her as to render it necessary for him to return to his home on the Westport River . After having repaired his boat, he again set off for Nantucket, reaching there in safety this time, and disposed of his cargo to good advantage. On a subsequent voyage, however, he was again taken by the pirates and deprived of all except his boat. Still, he continued his trips to Nantucket until he had acquired enough to look for a more lucrative business….

Having formed a connection with his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, who had several sons well qualified for the sea service, four of whom afterwards became captains and first mates, they built a vessel of twenty-five tons and made two successful voyages to the Strait of Belle-Isle.”

William Rotch’s memorandum, although perhaps written many years after the events therein described, nonetheless can be taken as reliable and accurate. The Ricketson report on Paul Cuffe’s adventures, however, seems to call for some possible revisions or corrections.

First, with regard to the brother who helped Paul build his first ship to travel to Nantucket, we conjecture that it was more likely to have been his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, than his brother, David. Michael and David were nearly the same age and 12 years older than Paul. Both had married in 1772, Michael to Paul’s sister, Mary; David to Hope Page, an indigenous woman from Freetown. We have speculated elsewhere that David may have joined Hope in her family home in Freetown, and that Michael may have joined Mary and her family on their farm near the Head of Westport. In 1776, Michael and Mary Wainer purchased a property at Russells Mills next to the Slocums River where Michael established a tanning business. This was the same year that Paul was released from the British prison ship in Brooklyn, New York, and returned to the family farm.

If Paul, based on what he had learned from fellow-prisoners from Nantucket about supply shortages on blockaded Nantucket, was contemplating attempting to respond to those needs and opportunities, his most likely brotherly ally would have been Michael Wainer, who had experience as a sailor and had just established a business on a nearby river that provided the shortest water route to Nantucket.

As for the boat that Paul might have used to carry on these activities, we believe it was unlikely that he had to build a new boat as there were many small craft that were not venturing into open waters or carrying on normal business, such as fishing or hauling cargo, because of the British naval blockade. Paul would have become acquainted with many of the local white farm owners when caring for their sheep on Cuttyhunk and after he had come with his family to the farm on Old County Road. Michael Wainer was also well-known in the area. If they informed local boat-owners that they were proposing to deliver supplies to the Quakers on Nantucket, those persons would more than likely have been willing to loan them their small sailing vessel that was sitting idle at their dock.

As for the home port of Paul’s Nantucket ventures, we believe that it most likely was Russells Mills at the head of the Slocums River. While we know that Paul Cuffe’s later shipbuilding activities were based on the Westport River, we do not have any specific references to where he based his mainland-based operations for supplying Nantucket. But, the fact that his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, had a tannery at Russells Mills from 1776 to 1792, that the Slocums River provided a waterway that could be easily travelled by shallops and other smaller sailing vessels but not by larger naval vessels, and that it was the closest, most direct harbor for accessing Nantucket from the mainland, all lead us to believe that this was where Paul Cuffe based his operations. It may also have been one of the ports which some of the smaller sailing vessels from Nantucket tried to reach to bring back supplies to their beleaguered island home. Paul Cuffe’s eventual success in making this run during the war, as chronicled by Ricketson, may have encouraged them, but they were probably much less familiar with the cuts through the Elizabeth Islands and hazards across Buzzards Bay than Paul Cuffe who had spent much of his boyhood exploring these waters.

Postwar Activities on the Westport River

After the War ended and there was no longer a blockade by the British Navy, the Westport River became an increasingly active port with supporting facilities on both sides of the river at Westport Point. Building of larger ships took place at both the Point and all the way up the East Branch to the Head of Westport where John Avery Parker and others constructed hulls and then floated them down the river with barrels strapped to their sides to enable passage through the shallow parts of the upper river. It was also necessary to take these hulls up on rollers and pull them by oxen around Hix Bridge. These hulls were then rigged and prepared for the sea at the Point.

Westport became an important whaling and fishing port, but so far as we know, was never a port for slave ships which mainly sailed out of Narragansett Bay on the South Coast. New Bedford became the most active port for whaling ships continuing up through the 1860s.

Postwar Activities at Russells Mills

After the war ended, Russells Mills probably diminished in importance as a port as the nearby major ports of New Bedford, Fairhaven and Padanaram were no longer subject to British naval harassment.

Michael and Mary Wainer continued to live at their home on the triangle at the center of Russells Mills until 1792. Paul Cuffe probably expanded his coastal and island shipping business along the Connecticut Coast and may have also engaged in some fishing trips to the Grand Banks and other popular fishing areas. He may have been sailing in and out of Russells Mills, but calling in at various ports along the South Coast such as New Bedford and Newport as well as the offshore islands.

On February 23, 1783, Paul married Alice Abel Pequit, an Indigenous woman who’s first husband, James Pequit, had recently died. Paul and Alice were married in Dartmouth and were recorded as living in an “Indian-style house” on a large 600-acre farm that Timothy Russell sold to William Snell Jr. of Bridgewater on September 23, 1783. The farm bordered on Destruction Brook northwest of Russells Mills and their house was probably within a mile of where Michael and Mary Wainer lived.

In 1787, Paul Cuffe is recorded as building a schooner, Sunfish, 25 tons and 42’3” length. There is no record of where this ship was built, but it seems reasonable to assume that it was built along the Slocums River below Russells Mills and that Michael Wainer was a partner in the project. Michael’s oldest son, Thomas, was then 14 years old and may have participated in the project.

Two years later, on March 19th ,1789, Paul Cuffe purchased from Isaac Soule the property on the western shore of the West Branch of the Westport River, that became his boatyard and was later expanded into his homestead. Before that purchase, he had no connection with the Westport River and no alternate site for building a ship than the Slocums River. After acquiring this property, he built 6 ships there ranging from 42 to 258 tons between the years 1792 to 1807. He also built a sizeable home on this property in the 1790s and his family moved there. In 1799 Paul bought a nearby 100-acre homestead property on the Westport River from Ebenezer Eddy on behalf of Michael and Mary Wainer who soon moved there with their family. They reimbursed Paul for this purchase in 1800 and Wainer family descendants have owned parts of this property ever since. It is now being transformed into a Native American Heritage Site by Wainer descendants.

[1] This paper has benefited from the comments of Richard Gifford and Betty Slade.

[2] See Cole and Gifford, 2020.

[3] Both the Gosnold Expedition that visited Cuttyhunk in 1602 and the Mayflower Expedition of 1620 carried shallops on board their larger ships to be used for getting from ship to shore when they reached their destinations.

[4] William Rotch, Memorandum Written In His 80th Year, Boston, 1916, quoted in Edouard A. Stackpole, Nantucket in the American Revolution. The Nantucket Historical Association, 1976. P. 52

[5] Ricketson, Daniel. The History of New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts. New Bedford, Published by the Author, 1858. Pp. 257-8.

This entry was posted in Uncategorized, Westport's Revolutionary Stories.