Risky Business: Following the threads of Westport’s short-lived silkworm enterprise

Posted on May 29, 2024 by Jenny ONeill

By Jenny O’Neill

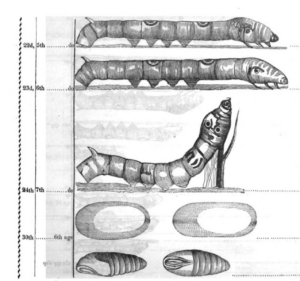

The Silk Culture in the United States by I. Richmond Barbour, Samuel Blydenburgh, 1844 CAPTION: This illustration depicts the life cycle of the silkworm. Ezra Stiles, President of Yale University and resident of Newport RI, authored an encyclopedic treatise on sericulture in the 1760s. He gave his silkworms names such as Oliver Cromwell, and fondly likened their behavior to newborn babies or a large company of sleeping children (Unravelled Dreams by Ben Marsh, 2020).

A most exotic and little-known aspect of Westport’s agricultural history is the activity known as “sericulture” — the production of silk, the rearing of silkworms, and the cultivation of mulberry trees.

The story remains incomplete and somewhat fragmented, with strands found within correspondence and journals chronicling the lives of the Macomber family of Central Village. I was first introduced to the presence of a small-scale silkworm industry by Norma Judson. Back in 2006, she (and the Westport Historical Commission) launched a campaign to raise funds for the restoration of the Wolf Pit School, offering mulberry trees in return for a monetary donation. This campaign was inspired by the story of Lydia Macomber (1811-1892), a deaf woman whose correspondence survives in the Westport Historical Society’s collection. Lydia grew up on the Macomber family farm in Central Village. Her father was deeply concerned about Lydia’s education, taking her to attend the American School for the Deaf in Hartford. In 1836 she described her involvement with raising silkworms:

“This summer we took care of silk-worms which contained about 16,000. There are forty-six pounds of cocoons, we get 10 cents a pound bounty from the state of Mass. My father told me that he with me will carry the cocoons to West Scituate, Mass. for me to learn to reel the cocoons on Brooks’ Patent Silk Spinning and Twisting Machine and it is sixty miles from our home.”

(CAPTION) Brooks’ Domestic Silk-Spinner, 1834. MECHANICS MAGAZINE. The Brooks Patent Silk Spinning Machine hailed as a “very ingenious machine for spinning and twisting silk” was invented by Adam Brooks of Scituate Mass. Even John Quincy Adams had an interest in Brooks’ invention. President Adams describes meeting Brooks who “brought some samples of sewing silk and of silk handkerchiefs, made by himself and his wife, from silk worms of their own raising…. His machine and silks were exhibited at the late Mechanics Fair in Boston, and again at that of the American Institute at New-York … Mrs Adams gave him her draw full of Cocoons, which she raised three years ago” (Diary of John Quincy Adams, December 4).

All members of the Macomber family had an interest in the business of silkworms. Lydia’s brother Alvah visited Rehoboth RI to see Joseph Healy’s silkworms “of which he has 400,000.”

Clarkson Macomber made note in his journal when they “moved the silkworms into the warehouse.” He later noted: “some of the silkworms began to spin.” (1833)

Raising silkworms provided a suitable activity for a young, deaf woman such as Lydia. Quakers and women had a special place in the growth of the silk industry. The homespun nature of home-produced silk attracted Quaker sensibilities. Sericulture was portrayed as a fascinatingly scientific yet undemanding industry with great economic potential, one of interest to merchants yet simple enough for farmers’ wives or daughters to undertake. Noted Pennsylvanian Quaker writer and activist Susanna “Suzy” Wright (1697-1784), raised silkworms in the 1770s, recording her process in the widely circulated article “Directions for the Management of Silk-Worms.”

Feeding the worms

Silkworms enjoy a specific diet of leaves from the mulberry tree. Lydia’s father John Macomber in partnership with Abner Brownell, planted a nursery of mulberry trees on his farm in Central Village. In 1833 Lydia’s brother Clarkson Macomber noted “this morning also trimmed some mulberry trees to furnish A. Brownell with silkworm feed.” Clarkson was also involved in planting trees at other local farms: “Cool and dry weather we are preparing to set out mulberry trees at Isaac farm.”

John Macomber attempted to improve the survival rate of the mulberry tree. Most varieties struggled to survive the cold temperatures of a New England winter. Renewed speculation sprouted around the introduction of a Chinese variety, morus multicaulis, a fast-growing type of black mulberry. John Macomber reported that during the extreme cold of winter 1835-36 “one half of his Perottet (morus multicaulis) mulberry trees survived and those which were engrafted upon the white mulberry not more than eight out of a hundred perished.” (A Manual Containing Information Respecting the Growth of the Mulberry Tree With Suitable Directions for the Culture of Silk by Jonathan Holmes Cobb, 1833).

The Silk Industry in America

A History: Prepared for the Centennial Exposition

By Linus Pierpont Brockett, 1876

John Macomber supplied Samuel Rodman of New Bedford with 10 white mulberry trees of two years growth (Diary of Samuel Rodman). In 1835 the Herald of the Times reported: “Messrs Brownell and Macomber of Westport Ma. have recently sold 20,000 mulberry trees to a silk cultivator in Providence.” (August 27, 1835)

An article appearing in the Newport History Bulletin Number 136, 1969 raises the possibility that their trees supplied raw silk for what was known as the Silk Mill near Sin and Flesh Brook, Tiverton. No further evidence of this has been discovered.

Both John Macomber and Abner Brownell became strong proponents of the silk industry and mulberry trees, writing letters to the agricultural publications of the era. John Macomber advocated for a bounty to encourage the growth of mulberry trees claiming that “the business rightly managed will in the process of time be beneficial to this Commonwealth … especially for the middling and poorer classes of the community.”

“The more that each of us does, the more he benefits his neighbor and impoverishes none by raising mulberry trees and converting leaves into silk, thereby promoting health, wealth, industry, good morals.” (New England Farmer, 1833).

In 1839 Brownell wrote: “we know of no sort of business which just now promises so golden a return as that of raising morus multicaulis. The production of silk remains to be more than double the net profits from the same land and labor than from any other agricultural production… A singular advantage arises in this business from its entire freedom from any risk.” (American Silk Grower, 1839)

Silk companies such as the American Silk Company on Nantucket and a silk factory in New Bedford owned by Joseph Rotch (New Bedford City Directory, 1836) sprang into being during the 1830s. The silkworm “craze” spread far more widely throughout Connecticut. However, within two decades, the industry had collapsed. The New England winters proved to be too harsh for the delicate mulberry tree, and following The Panic of 1837, the silk bubble burst. In March 1837 Abner Brownell sought to sell the “whole of his nursery trees, including 40,000 mulberry trees at a small price.” He lost “considerable money in this enterprise.” (Representative Men and Old Families of Rhode Island, 1908)

Fall River Monitor and Weekly Recorder Saturday March 18 1837

The full story of this unusual aspect of Westport’s history is yet to be unraveled. Further information is likely to surface as more local newspapers and agricultural journals are digitized. May these strands lead future historians to a more complete understanding of this story.

With thanks to Richard Gifford, Bob Maker, and Robin Winters.

Macomber family resources available at the Westport Historical Society:

The Journal of Clarkson Macomber

Correspondence of Lydia Macomber

Notes on the John Macomber farm by Richard Gifford

Marianna Macomber’s memoir about the Macomber family of Central Village

Ordinary Lives Recovering Deaf Social History through the American Census by Eric C. Nystrom and R.A.R. Edwards, University of Massachusetts Press, 2024

The Silk Culture in the United States by I. Richmond Barbour, Samuel Blydenburgh, 1844

CAPTION: This illustration depicts the life cycle of the silkworm. Ezra Stiles, President of Yale University and resident of Newport RI, authored an encyclopedic treatise on sericulture in the 1760s. He gave his silkworms names such as Oliver Cromwell, and fondly likened their behavior to newborn babies or a large company of sleeping children (Unravelled Dreams by Ben Marsh, 2020).

The Silk Industry in America

A History: Prepared for the Centennial Exposition

By Linus Pierpont Brockett, 1876