“Degeneracy, Profligacy, and Imbecility” – American Politics in 1800

Posted on February 7, 2020 by Jenny ONeill

One of the most cited reason for studying history is to learn from the past. While that is true, there is another key purpose that is mentioned far less often: reflection. Through this newspaper before us, the Boston Gazette, we can see a world not dissimilar from our own. In fact, you could even say the politics of 1800 were even more troubled than today’s. While perhaps not as instantly comforting as “it will get better,” being able to say “it could be worse” can prove to be far more reassuring in the long term.

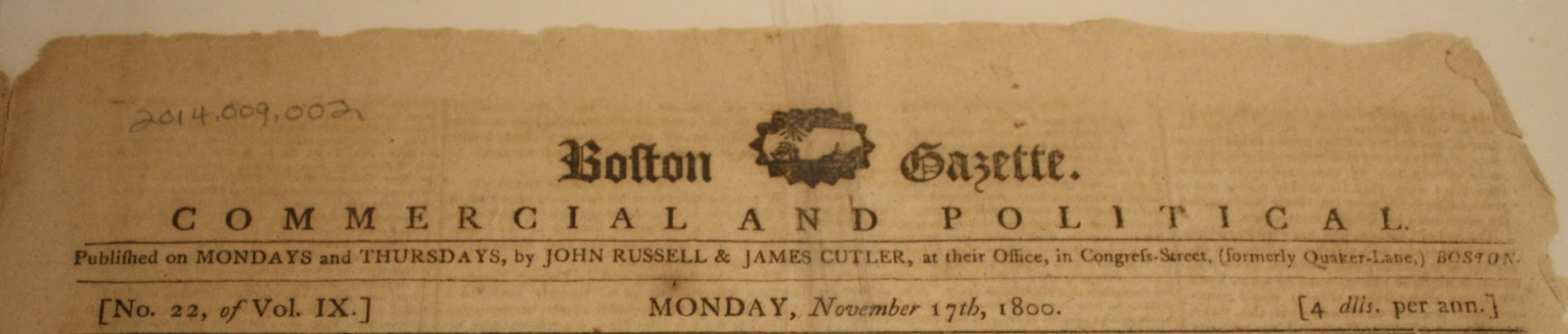

One of the most interesting points in our country’s history is its beginning. The first generation of Americans set the stage for the next 240 years of our nation, establishing precedents that guide us to this very day. However, rarely do you get to see the world through their eyes. The only way to do so would be to immerse yourself in their literature, and no piece of writing defines early America like the newspaper. In particular, we are discussing the Boston Gazette’s No. 22, Volume 9, published November 17th, 1800. This was in the middle of the nation’s fourth election, and would see Thomas Jefferson run against Incumbent President John Adams.

Revolution of 1800

This paper was published just moments before the “Revolution of 1800”, which was the first proper American election, and set the precedent followed ever since. Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republicans supported a more rural, “democratic” America, while the incumbent John Adams of the Federalists represented the urban elites and aristocracy. For example, Virginia was the Jeffersonians base, while New England belonged to Adams. This election was so contentious that the Electoral College could not decide it alone, and the debate went to the House. With a difference of a single vote, they would elect Thomas Jefferson to be our nation’s 3rd President.

The tightness of Jefferson’s victory was a result of the brutal campaigns run by both parties. Federalists argued that Jeffersonian rule would erode all national morals (there is a common theme in smear pieces that he would legalize rape and prostitution), whilst the Jeffersonians concluded that another four years of Adams would destroy the American Experiment, citing his infamous Alien and Sedition Acts. The former made it incredibly difficult for immigrants to enter the nation, and the latter eliminated the free press, so it could be argued Jefferson’s band did have a point.

Whilst this paper sadly does not include James Callander’s famous article condemning President Adams, “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman”, it does provide perspective as to how the Massachusetts citizen felt during the time. One would expect unabashed optimism, as the native son was seemingly a hair away from having the highest office in the land for another four years. However, there is more of an uneasy feeling about the election, which was mostly due to the troubles within Adams’ party.

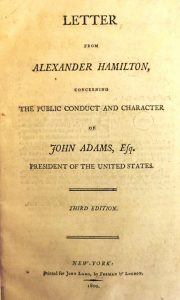

The Federalist Party had two leaders; John Adams who represented the more aristocratic wing, and Alexander Hamilton who attracted the fiscally minded voters. Naturally, a clash of personalities was inevitable, and the two titans destroyed one another in the press. Letter after letter was published, and in the end well over a hundred pages of lethal ink were put out for all to see – several are advertised throughout this issue alone. This is widely regarded as the moment that began the end of the entire Federalist Party. The opposition had a strong, nearly unopposed leader with Jefferson, while the Federalists spent the election cycle destroying their highest ranking members.

What also deserves note is the section labeled Political Miscellany, written by a South Carolinian. This article addresses the already apparent sectionalism in the United States, and gives a sign that politics will only become more hostile in the years ahead. It would be criminal to alter these words: “if we read the pamphlets which pour upon us from the northern states, if we attend the conversations at the democratic clubs, we shall see such a picture of degeneracy, profligacy and imbecility … at the first view we find it impossible to not to exclaim ‘the country is ruined!’” The article even ends on a call to arms for the residents of South Carolina, saying that if those who write about Federalists destroying the Constitution truly believe their words, they ought to, “rise up in arms against the constituted authorities, and never lay them down until the Constitution is safe,” and if they do not, they prove that they are simply hoping the public falls for “nothing more than the tricks of disappointed ambition.” After all, he theorizes, these writers are little more than politically ambitious, self-appointed intellectuals who are waiting for their government appointment which will never come.

While this document appears at face value to simply be a piece of parchment, dated and obsolete by all accounts, it is truly a piece of incredible value. Granted, probably not in the monetary sense. Instead, its value lies in the insight it is able to give into a time not unlike our own. By examining the crises of yesteryear, we can gain perspective on our own, and can even use their remedies once more. We are truly fortunate to have documents like this – especially in times like our own.

Mark Allen

Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States cover

Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States cover