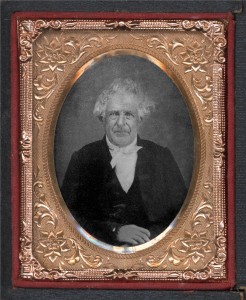

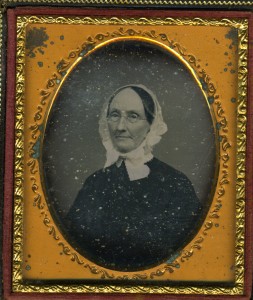

Dr. James and Hope Handy

James Harvey Handy married Hope White on August 28, 1817, in Taunton, Massachusetts.82 Hope White is thought to have been born on October 21, 1791, the daughter of Cornelius and Eliphal White of Westport.83 It had been previously thought that this line of White was not related to William White, husband of Elizabeth Cadman, and for whom the Cadman-White-Handy house was built; however, this may not be the case. A study of Hope’s family tree reveals William White was Hope’s great-great-grandfather on her father’s side.84

James and Hope Handy had three children that survived past infancy, two sons, and a daughter:

- William White Handy (b. February 20, 1819 in Westport, MA. d. May 18, 1886 in Fall River, MA)

- Eli Handy (b. February 20, 1826 in Westport, MA. d. April 16, 1839 in Westport, MA)

- Eliphal Almy Handy (b. circa 1831 in Westport, MA. d. Unknown)

While William lived a full live, the same was not true for his younger siblings. Eli died just a few months following his thirteenth birthday. The cause of his death is not known. Little is known about Eliphal Almy Handy (named after her maternal grandmother Eliphal Almy). Eliphal is identified in the 1850 Federal census together with her parents. She is 19 years old when the census was taken, placing her year of birth either in late 1830, or prior to October 1831.85 In the 1860 census, Eliphal Almy Handy is not listed; instead, Eliphal Almy Gibbs, age 7 is listed as living with James and Hope. Eliphal Almy Gibbs is identified in a Petition for Probate submitted by Robert S. Gibbs concerning Hope Handy’s estate. In the petition, it states:

“E. Almy Gibbs a minor daughter of the said Robert S. Gibbs residing in said Fall River and a granddaughter of the said Hope W. Handy.”86

In records currently available, Eliphal Almy Handy’s name does not show up again until she is mentioned in Hannah Handy’s (James’ sister) will. In it, Hannah writes:

“I give and bequeath to Eliphal Almy Brown, daughter of Robert S. Gibbs and my niece Eliphal Almy Gibbs [italics add by author], five dollars in money…”87

Aside from these fleeting references, little else is presently known about either Eliphal Almy. Based on the few details that are known, there is undoubtedly an intriguing story here that must be further explored.

Like his father, James Handy was also a physician; however, unlike his father, James held a number of public positions at both local and state levels. James is listed as a Justice of the Peace in The Massachusetts Register beginning in 1830.88 Between 1831 and 1835, then again in 1841, James served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.89 Aside from listed as serving in the House, little is known about his work and/or accomplishments as a result of his service. During his tenure in the General Court, James is recorded as attending an Anti-Masonic Republican Convention held in Boston, Massachusetts in 1833.90 The convention was attended by delegates, “…chosen by the antimasonic [sic] people of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, from eleven Counties…for the purpose of consulting upon the common good, seeking redress of wrongs and grievances suffered from Secret Societies, nominating candidates for Governor, and Lieutenant Governor, and generally to transact such business as the cause of Antimasonry [sic] may require,” with a prevailing theme that “… Secret Societies are inconsistent with a free government, and that Freemasonry must be abolished, and without delay, is widely diffusing itself among an intelligent and patriotic people.” 91 James’s presence at the convention would indicate he shared in this anti-Masonic belief; however, how active in this cause and to what degree he embraced it needs further research.

It is not known if James received any formal education as a youth. Considering his upbringing (son of a physician and person of moderate means,) profession, and various positions in government, it would suggest he benefited from some degree of schooling.

James acquired his father’s house in 1812 as part of the terms of Ely’s will. The inventory of Ely’s possessions valued his real estate as, “The homestead of said deceased situated in said Westport containing about sixty three acres with the buildings there on $2,700.00.”92

As mentioned in the previous chapter (Ely Handy and Mary Brownell), following Ely’s death, his wife Mary, in lieu of dower, was given the right to live in the house for the remainder of her life or “… so long as she shall remain my widow.” Similar rights were given to James’ sisters, Polly and Hannah. Both were granted “… a home at my dwelling House and a comfortable support and maintenance both in health and sickness, so long as she shall remain single, and unmarried. But if she should marry I give her in lieu of her said home and maintenance two hundred dollars.”93

It is not known how much property, if any, James Handy owned prior to inheriting his father’s farm; however, in the years following, both James and his wife were involved in numerous land transactions. While the majority of these transfers involved the buying and selling of land between individuals, a few transfers came about as a consequence of debt settlements, where the appraised land of a debtor was seized by the courts and granted to the individual which money was owed.

While James Handy was on the receiving end of a few of these transfers, ultimately, it would be he who was named as the debtor of one such case, resulting in the loss of a large holding of real estate, part of which included the homestead farm and its land (see December 4, 1861 debt settlement between George Kirby and James Handy). Attached to the end of this chapter is a summary of the known land transactions involving James Handy (and in some instances his wife Hope,) between 1814 and his death in 1868.

One acquisition worth discussing was James’ purchase of a farm from John A. Parker on February 2, 1814.94 It is interesting to note that this trans action occurred prior to James marrying in 1817. The farm as described in the deed consisted of two lots divided by the East branch of the Accoxet River and contained a total of fifty-six acres, fifty acres on the West side and six on the East side. The purchase included “…the Bridge crossing said river, called Hixes Bridge, and the wharf, and store thereon, on the west side of said river, contiguous to said Bridge with the Barns and sheds standing near said farm on Towns land with all other Buildings and appurtenances belonging to said farm, bridge, and wharf…” Though James is identified as the sole grantee in the deed, in reality, as the archive informs us, this was not the case.

In a story that to those well acquainted with the Handy house may already be familiar with, the purchase of the farm and bridge was conducted not solely by James, but included his future brother-in-law, Frederick Brownell. There was an agreement between James and Frederick that James would purchase the farm and bridge and turn the land east of Drift Road over to Frederick, who would operate the store located at the West end of the bridge and collect the tolls as well. In exchange for this, Frederick was to pay James 2,100.00, $700.00 initially and the remaining $2,100.00 as soon as he could. Despite having paid James for his portion of the property, Frederick never received a deed for it. In fact, though Frederick had paid James the $2,100.00 he owed him, it is claimed James had a bill at Frederick’s store that exceeded $3,600.00, which included the amount paid for the property. It is believed that James never showed or claimed interest in the property Frederick operated.95

Henry B. Worth, the early twentieth century New Bedford real estate lawyer, historian, and genealogist, explained the resolution of this matter in his notes on the Handy family and property. He concluded that :

“In 1861, Frederick Brownell conveyed the Bridge and all the land connected with the same, as far west as the Drift Road, to his son Giles E. Brownell. But [sic] Dr. Handy never transferred any part of the property to Frederick. In 1873, Giles E. Brownell wanted to sell the property, but there was serious trouble with the title but [sic] the administrator of the estate of Dr. Handy put up the interest of the doctor in the property at auction, and it was sold to Wm. B. Trafford for $35, and was at once transferred to Giles E. Brownell. It [the sale] covered all the interest that James H. Handy had in the bridge and land on both sides of the river, 6 acres on east and 4 acres on west, being part of what John A. Parker sold to Handy in 1814. The reason why it brought so little was that the claim on it by Brownell was so well substantiated that it showed the doctor did not own much in it.” Worth further elaborates on the details of the matter by explaining, “… In the early part of 1871 the Town laid out the bridge as a town way and made an award of $1800. for it to be paid to the bridge owners whomever they might be. The administrator of Dr. Handy’s estate, Capt. Joseph C. Little, claimed the fund and so did Giles E. Brownell. A lawsuit was impending. To force the fight, Capt. Little sold the interest of Doctor Handy in the property, as shown on page 13 [of Worth’s notebook], and Giles Brownell bought it. This ended the controversy and Brownell obtained the award and the land.”96

Perhaps the most significant action documented in the Land Records during this period directly impacting the Handy house parcel occurred in 1861 and details James’ loss of the house and land as a result of debt settlement to one George Kirby. Henry Worth refers to this dispute in his notes about Dr. Handy. Worth claims in his writings that: “After the death of Eli, the son [James] built the West end of the House and he borrowed some money from the sister of George Kirby to do it — and never paid anything on the debt. So in 1861, George Kirby seized some of the real estate of the Doctor on execution and took it.”97

This would seem to indicate that James was responsible for building the west addition (Period III) to the house, sometime after May 1812.

Based on the information recorded in the debt settlement, which took place on September 9, 1861, in the Taunton Superior Court, a judgment for $3,965.95 in damages, together with an additional $26.32 for the “cost of writ” was ruled against James H. Handy to satisfy a debt owed to George Kirby (an enormous sum for the time.) In order to satisfy his debt, the courts appointed three “disinterested and discreet” men to apprise the real estate of James H. Handy. While James had the right to choose an appraiser, he neglected to do so.

The appraisers examined three separate parcels owned by Handy. They were described as follows:

“Beginning at the East line of land formerly owned by Barney Hicks, deceased, in the Northerly line of the Highway that leads Westerly from Hick’s Bridge so called, to Adraon Davis in said Westport. Thence Northerly in the line of said Hick’s Land, to land of Matthias E. Gammons. Thence Easterly in the line of said Gammons land to the highway that leads southerly from the Head of Westport River so called, by the Westport Alms House to said Hick’s Bridge. Thence Southerly in the West line of said Highway to the said Highway first above named. Thence in the northerly line of said Highway to the first mentioned place of beginning. Situated on the Easterly side of said Highway leading from the Head of Westport River, so called to Hick’s Bridge so called. Bounded and described as follows. Also one other parcel of Real Estate, Situated on the Easterly side of said Highway leading from the Head of Westport River, so called to Hick’s Bridge so called. Bounded and described as follows. Beginning at the Southerly line of land owned by Matthias E. Gammons and in the Easterly line of said Highway. Thence Easterly in the line of said Gammons land to the East branch of Acoaxet River so call. Thence Southerly by the said River to the South East corner of the Homestead Farm of Ely Handy late of said Westport, deceased, and line of land owned by John Milk, now or formerly. Thence Westerly by the stonewall about Twenty-six and one quarter rods to the said Highway which leads from said Head of Westport River, so call by the Westport Alms House to said Hick’s Bridge so called. Thence in the Easterly line of said Highway to the place of beginning. And we have appraised the whole of the above described Real Estate including the premises therein. Assigned to Mary Handy, widow of said Ely Handy, deceased for Dower in her said husband’s Estate, at the sum of Eighteen Hundred Dollars, from which amount we have deducted the sum of One Hundred and fifty Dollars as the value of said Mary Handy’s Dower, assigned therein, leaving a balance of Sixteen Hundred and fifty Dollars as the value of the said James H. Handy’s Estate, therein including the revision of the said Dower, and have set it off the same as aforesaid by Metes and Bounds to the said George Kirby.” [Authors Note: This is the parcel with the dwelling house]

“…on the southerly side of aforesaid Highway leading from Hick’s Bridge so called. Westerly to Adraon Davis, Bounded and described as follows. Beginning in the south line of said Highway, and in the West line of the Highway leaving by the Dwelling House of Ephraim Briggs, it being the North East Corner of the lot, Thence southerly in the west line of said last named Highway about thirty five and one half rods to land of the said Ephraim Briggs. Thence Westerly in the line of said Stone Wall. Thence Southerly by the sandstone wall and line land of [Green] Allen. Thence Westerly in the line of said Allen’s land about Thirty-nine rods to land formerly owned by Richard Gifford deceased. Thence Northerly by a Stone Wall in the said Gifford line to the Highway first above mentioned. Thence Easterly in the South line of said Highway about one hundred fifty seven and three fourth rods to the place of beginning. And we have appraised said Real Estate that the sum of $900 and have set off the same as aforesaid by Metes and Bounds to the said George Kirby…”

“…one undivided half part of about four acres be the same more or less of swampland. Situated in Dartmouth… Being the premises which the said James H. Handy purchased of Othmil Tripp as Administrator of the Estate of Lemuel Milk, late of said Westport, deceased, by Deed dated January 18th, 1821 Recorded in the Land Records of the Northern District of said County of Bristol, Book 126, Page 227. Reference lot to said Deed for a more particular description, said tract of land being held by the said James H. Handy as tenant in Common with the heirs of Job Milk, of said Westport deceased (or whoever else the present owner may be.) And we have appraised the whole of said tract of land at the sum of One Hundred + Thirty Dollars and the share of the said James H. Handy therein being one undivided Half part at Sixty Five Dollars, and have set off the said undivided share as aforesaid to the said George Kirby…”

Following the appraisal of James’s real-estate, it was determined that,

“…the whole of said Real Estate including the premises thereon, assigned to Mary Handy, widow of Ely Handy, of said Westport, deceased, for Dower in her said husband’s Estate, at the sum of Twenty Seven Hundred and Sixty Five Dollars, from which amount they deducted the sum of one hundred and fifty Dollars as the value of the said Mary Handy’s Dower, assigned therein, leaving a balance of Twenty Six Hundred and fifteen Dollars as the value of the said James H. Handy’s Estate in the whole of the aforesaid described Real Estate including the revision of the said Dower, from which last named amount I have deducted the sum of Sixty two Dollars and thirty cents for my fees and charges, and have applied the amount of the balance, amounting to the sum of Twenty Five Hundred fifty two dollars + seventy cents in part satisfaction of this Execution, and have set off said Real Estate as aforesaid, by metes and bounds to the said George Kirby… As described in said appraisers certificate above written… And I this day levied this Execution upon said Real Estate as aforesaid described as aforesaid and delivered seizure and possession thereof to the said George Kirby the creditor… in part satisfaction of this execution, to wit, for the sum of Twenty five Hundred fifty two Dollars and Seventy cents…Received and Recorded December 13, 1861”

All said, after deducting Mary Handy’s dower, along with courts fees, James’s real estate was valued at $2,552.70, all of which was transferred at this time to George Kirby as partial satisfaction of James’s debt. What became of the additional $1,413.25 James owed George is not known.

A more curious question to ask is to what extent this judgment affected James and Hope’s living conditions.

Hope Handy died April 21, 1864. In her will, she left her father’s farm in Westport to her son, William and his wife, Caroline, it being, “… the farm on which my said son now lives.” She also left them, “… a lot of land situated in Dartmouth…containing nine acres and one hundred and forty rods of land.” Following William and Caroline’s death, the farm was to be passed to their two sons, Eli Handy, and George Edward Handy; their sister was to receive $400.00. The remainder of Hope’s estate was left to her granddaughter, E. Almy Gibbs.

Dr. James H. Handy died on May 15, 1868, in Westport. Surprisingly, he did not leave a will, and as a result, his estate was settled through the courts. Records show that the probate process was lengthy, continuing through October 1873. Immediately following his death, a court appointed administrator was assigned to handle James’ estate; however, in November 1868, William Handy requested, and was granted, administrator of his father’s estate. Nearly four years later, William had failed to settle James’ estate, and resigned from his role as administrator. Joseph C. Little, a court appointed administrator was assigned to complete the matter. The remainder of Handy’s estate was valued at $3,402.36 : $1,280.00 in real estate and $2,122.36 in personal estate. Surprisingly, the real estate consisted of the Hix Bridge Farm, which formed the basis of the Brownell dispute (above).

Footnotes

82 Vital Records of Westport Massachusetts to the Year 1850. The New England Historic Genealogical Society. Boston, Massachusetts. 1918. p. 171.

83 Descendants of Zaccheus Handy. Generation 3. Handy FamilyPDF.pdf, Westport Historical Society archives.

84 Ancestry.com, http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/304048/family?cfpid=6049905481 The accuracy of this research must be verified. As it is stated, Hope White’s father, Cornelius White (1762-1800) is the son of Israel White (1730-1785). Israel’s father is identified as George White (1710-1764), the eldest son of William and Elizabeth (Cadman) White.

85 The census sheet Dr. James Handy and his family appears on is dated October 13, 1850.

86 Hope Handy, Petition for Probate, dated May, 2 1865, Volume 2, page 60, Probate Court, Bristol County, Massachusetts.

87 Will of Hannah Handy, undated, probated March 16, 1893, Bristol County, Massachusetts.

88 The Massachusetts Register and United States Calendar. Richardson, Lord, Holbrook, and Loring: Boston, 1830. p. 60. James is continually listed as a Justice of the Peace in subsequent editions through 1847, the last register available for review.

89 Hurd, Duane Hamilton. History of Bristol County Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men. J.W. Lewis and Company, 1883, p. 695.

90 Antimasonic Republican Convention of Massachusetts: Held at Boston, Massachusetts, September 11, 12 & 13, 1833, For the Nomination of Candidates for Governor and Lt. Governor of the Commonwealth. J. Howe:Boston. 1833. p. 46.

91 Ibid, 3, 17

92 Probate inventory of Ely Handy, May 5, 1812.

93 Will of Ely Handy, Dated September 2, 1811, probated May 5, 1812, Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County Probate & Family Court Registry, Vol. 47, pp. 223.

94 John A. Parker to James H. Handy, 2 February 1814,

Bristol County, Massachusetts, Deed Book 21, Westport, Massachusetts.

95 This information concerning James Handy and Frederick Brownell’s agreement and the ensuing dispute has been gleaned from notes gathered from Henry B. Worth’s personal notebook contained in a Westport Historical Society digital file titled, Henry B. Worth notebook.doc. Worth’s original notebooks and manuscripts are located in the New Bedford Whaling Museum Research Library, Henry Barnard Worth Papers, 1714 – 1942, Mss 59

96 Ibid, Henry B. Worth notebook.doc

97 Ibid, Henry B. Worth notebook.doc. Page 3.

Eric Gradoia, Architectural History and Conservation. Copyright 2014