Abbott Smith 1911 – 1937

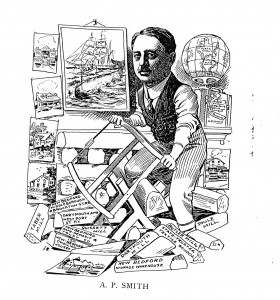

Abbott Pliny Smith is perhaps best known for being an accomplished New Bedford businessman, with a career spanning nearly seventy years that included involvement in whaling, real estate development, the building of numerous mills and other commercial ventures, as well as the construction of a number of local railway systems.

Abbott Smith married Sarah Emeline Metcalf January 15, 1879. They had three children that survived past infancy:

- Florence R. Smith (b. August 11, 1881, d. May 3, 1977)

- Ruth Smith (b. Unknown, d. Unknown)

- Abbott M. Smith (b. November 11, 1890, d. April 13, 1967)

Abbott Smith was born to Henry and Ruth (Wilcox) Smith on a farm in Westport on October 7, 1853. Both Henry Smith and his father-in-law, Henry Wilcox, were agents in the whaling industry. Henry Wilcox owned shares in a number of barks including the Theophilus Chase (operated between 1844-1847), Rajah (1844-1847), Janet (1848-1869), Governor Carver (1850-1867), Mexico, a brig (1853), Mattapoisett (1851-1860), and Greyhound (1851-1860). Both Henry Smith, and Abbott would go on to act as agents for the Mattapoisett (1860 and 1886) and the Greyhound (1860-1920). Abbott’s father passed away on October 28, 1873, just a couple of weeks after Abbott’s twentieth birthday. Following his father’s death, he assumed the responsibilities of agent for the barks Greyhound and Mattapoisett, a practice he continued for approximately 12 years (1885).122

On September 15, 1876, Abbott set sail from Boston, Massachusetts aboard the Azor, a supply ship servicing whalers in the Azores. These ships typically carried fresh supplies to the whale ships operating out of foreign ports and in turn returned to New Bedford with whale oil the whalers had gathered during their tours at sea. Seizing the opportunity that presented itself, Abbott continued his travels far beyond the Azores over the better part of the following year, venturing on to Madeira, Lisbon, Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt, Palestine, Constantinople, Russia, Slovakia, Holland, Austria, Italy, Switzerland, and various other parts of Europe.123

As the whaling industry began to wane, Abbott shifted his activities into other enterprises. By 1880, Abbott Smith ventured into real estate development, constructing numerous houses and stores throughout New Bedford. He went on to build the Acushnet Railway in 1885, and promoted the New Bedford Safe Deposit and Trust Company, serving as the first vice president of the company. In 1894, Smith went on to build the Dartmouth and Westport Railway, and in 1898, he built the Middleboro and Brockton Railway. The 1890s saw Abbott involved in the promotion and building of a number of mills including the Dartmouth Mill (1895), Soule Mill (1901), Butler Mill (1902), Kilburn Mill (1905), Tabor Mill (1906), Quansett Mill (1907), and the Quisett Mill (1910). In 1910, Abbott also opened the New Bedford Storage warehouse, one of Abbott’s last ventures was the promotion of the Old Colony Silk Mills Corporation in 1925.124

While Abbott held memberships to numerous public and private clubs. A number of these memberships were with history-based organizations. With respect to his family history, Abbott was a member of both the Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants and the Sons of the American Revolution. Abbott was also a member of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England), a regional museum organization formed in 1910 with a focus on collecting and preserving objects from New England life. At a local level, Smith was actively involved with the Old Dartmouth Historical Society (which eventually became the New Bedford Whaling Museum).

Abbott is also known to have attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. While the official title of the exposition was the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufacturers, and Products of the Soil and Mine, the unofficial theme celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Highlighting this theme were a great many exhibits celebrating the life and times of colonial America, including reconstructions of eighteenth century American buildings, exhibits of “colonial” furniture and the construction of a “New England Log-House,” filled with “… old fashioned furniture and Revolutionary relics.” For those readers familiar with the exposition, this was the site of the colonial kitchen built as a contrast to the modern 1876 kitchen. [Ingram, J. S. The Centennial Exposition, Described and Illustrated, Being A Concise and Graphic Description of this Grand Enterprise. Hubbard Brothers: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1876. pp. 706-708.

Abbott Smith was sixty-seven years old when he purchased the Handy house and thirty-five acres from Daniel W. Baker on July 9, 1920.125 He purchased it for the property taxes due for that year. Abbott’s primary residence was 95 Hawthorn Street in New Bedford and he continued to live there even after acquiring the Handy house. Although he made numerous repairs and improvements to the house over the sixteen years he owned it, the Handy house was never his primary residence. By all indications, the Handy house appears to have been a retreat of sorts for him.

An interesting reference found in a document held by the Westport Historical Society suggests Abbott either may have had greater plans for the house or was simply celebrating his take on the history of the house. The document states:

“Coughlin (who lived across the road) said there was once outside stairs for the “help” to use when Abbott was planning to have it for a Tavern. The east end [attic] floor still has grass matting and there was a closet too! Louis [Tripp] used those boards. There was also a very nice sign with black background + gold letters “Handy Tavern.” This Louis gave to the “Men’s Club.” The “Club” was in the barn on the corner of Adamsville + Main Road. The men were raising money selling donated items.”126

Abbott’s period of ownership was the first era captured to any great degree in photographs, with numerous images of both the exterior and the interior. Close study of these images tell us a lot about both Abbott Smith and the house. By all indications, Abbott was the quintessential follower of the Colonial Revival movement popular in America during the latter half of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth century. It is clear by the organizations he was a member of that Abbott had a strong interest in American colonial history, especially as it related to his ancestry and the area he was born and raised in. His photographs of the Handy house show us that he had an extensive collection of “colonial” period (i.e., seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century) antiques composed of furniture, textiles, framed art, ceramics, and ironwork among other things. When looked at in this context, his purchase of the Handy house appears to be a logical addition to his collection. A typed document that appears to chronicle Louis Tripp’s (see following section) purchase of the house from Abbott Smith contains a single sentence that seemingly explains why Abbott bought the Handy house:

“He [Abbott Smith] said the reason he bought the property in the first place was because I was born in Westport and Dr. Handy was our family physician, so from boyhood [I] was interested in this estate.”127 [Italics added by the author]

Based on early twentieth century photographs of the Handy house, by the time Abbott took possession of the building, it appears that it was very much in need of considerable work.128 No records detailing the full extent of improvements made by Abbott are known; however, based on his photographs of the building and the remaining physical fabric, it appears Abbott was responsible for:

- Residing the exterior sidewalls. This probably entailed some frame/vertical plank repairs as well. The East wall of the first floor may have been reframed (either partially or in its entirety) at this time.

- Removing the two frontispieces and doors at the South entries replacing them with simple, relatively unadorned frames with sidelights.

- Construction of a large, semi-enclosed porch on the front (south elevation) of the building. This included converting the westernmost window opening on the first floor into a door opening, necessitating the moving of the bulkhead here around the corner, to the West side of the building.

- Construction of the dormers on the north and south sides of the roof. Presumably, this was done to provide habitable space throughout the attic of the building. As photographs show a number of the first and second floor rooms fitted with beds (all antiques), it may be that the attic was relegated to servants and/ or guest lodging, storage or a combination of these.

- Installation of an electrical service to the building.

While Abbott’s exterior improvements considerably altered the outward appearance of the building, it appears he did little to change the interior of the house, largely respecting what was there. Based on Abbott’s photographs of the interior, it appears he wallpapered all of the rooms as part of his renovations. This would suggest he likely painted the woodwork in a number of the rooms at this time as well, although he respected those surfaces that either had never been painted or had only a single coat applied.

While practically no records are known chronicling Abbott Smith’s use of the Handy house, one particularly vivid account written by his grandson, Abbott, has come to light. The article is his grandson’s account of a Thanksgiving dinner Abbott held at the Handy house in 1927. He wrote of the event:

“The logistical and culinary planning and execution of such an affair was delegated to the family butler (Maurice), who proved stunningly up to the task… Pots, pans, china, silverware and high and low chairs were volunteered and delivered by various families…And such food as turkey and pies that could be all or partially precooked was done that way in various family kitchens, and delivered to our family cook, Anna.”

Young Abbott wrote that he particularly recalled the noise level,

- “being quite high as impatience and hunger stirred up the volubility and some crying and screaming by hungry young” as well as the adults who competed to be heard above the crowd. At 3 p.m., after his grandfather led the crowd in a prayer of Thanksgiving, dinner was served. “Various ‘borrowed’ maids and Maurice scurried hither and yon feeding the tribe,” wrote Smith. “The gargantuan turkeys were carved at both ends of the table, one by Grandpa and the other by Uncle Arthur Delano, a senior-in-law. “The maids did yeoman service keeping everyone’s plate full, following Maurice’s quiet directions from the house dining room where he could observe everything by opening the door just a crack.

“The major event — an accident, really — happened as the gravy was being served,” wrote Smith. “Maurice appeared with a large gravy boat and started down the outside of the table. Suddenly he lost his footing on the unfamiliar floor, the gravy boat crashed, and a river of gravy started to flow down the wooden porch floor. At the same instant, some of us could see a strange object scudding along on the top of the gravy river,” he recalled. “It was Maurice’s perfect toupee, upside down in the stream of gravy (and) at the same time, stretched out fully was shiny pated Maurice, swimming face down in the flow.”

“Once he grabbed his toupee and stood up to expose his soiled tux and shamed face, some people (like me) just couldn’t keep from laughing briefly,” he said. “Finally, we all bushed and stored up our laughing for some later and more private time.” The red-faced butler would not be seen again that day, said Smith, although his “trembling voice could be heard from behind the door instructing the maids on whom to serve next, and we also heard the occasional restrained tittering of the girls as they passed him going in and out.” Smith said no one had a clue that the butler’s perfectly-coiffed headpiece was not his own hair. “His humiliation was felt by all.”

After the Maurice incident, the family agreed “such a massive family meeting was not to be attempted again…the strain was just too great.”129

Abbott Smith sold the Handy house to Louis and Florence Tripp in September 1936. On March 8, 1943, Abbott Smith suffered a fall resulting in a fractured hip. Ten days later, while still recuperating in the hospital, Abbott passed away as a result of complications brought on by his accident. He was 89 years old.

Footnotes

122 Smith Family Whaling Ships. Document of the Westport Historical Society archives. Westport Historical Society, Westport, Massachusetts.

123 “Abbott Smith, 89, Succumbs; Was Business, Civic Leader.” The Standard Times, New Bedford, Massachusetts. March 18, 1943.

124 “Abbott Smith Observes His 80th Birthday.” The Standard Times, New Bedford, Massachusetts. 1933. Photocopy of newspaper article. Westport Historical Society archives. Westport Historical Society, Westport, Massachusetts.

125 Daniel W. Baker to Abbott P. Smith, 9 July 1920, Bristol County, Massachusetts, Deed Book 503, Pages 295-296.

126 Unidentified handwritten note, likely Eleanor Tripp’s. Collections of the Westport Historical Society. Westport, Massachusetts.

127 Type written notes from the Handy house scrapbook. HH B2 I/R 36-90 folder, Westport Historical Society, Westport, Massachusetts.

128 For a more detailed account of the changes and improvements made to the house see The Cadman-White-Handy House Architectural Investigation, October 2011. Westport Historical Society archives, Westport, Massachusetts.

129 Westport Historical Society. (November 22, 2013) “A Handy House Thanksgiving.” Retrieved from Westport Historical Society online. http://wpthistory.org/news/archives/000551.html 29 January 2014.