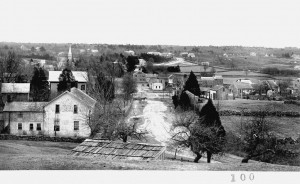

Head of Westport

The Head of Westport, known early in the historic period as Westport Village, was initially settled by Euro-Americans around 1671 with the construction of a home by Richard Sisson. Sisson’s original homestead was supposed to have been located near 137 Drift Road, but was burned during King Philip’s War. A second home was built in the general location of the stone house that sits just south of the triangle at the Head, and Wilcox may have operated a tavern there in the early eighteenth century (WHC 1987:19).

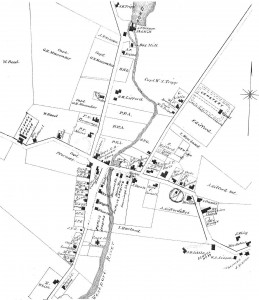

Daniel Wilcox was another seventeenth-century settler; his farmstead was located on the east side of the East Branch and extended south to the area around Hix Bridge Road. Wilcox’s homestead was supposed to have been located on a long-term Native American campsite known as Wasontuxsett in an area below Pine Hill Road (WHC 1987:18). A few other families settled this general area prior to 1700, including members of the Mott, Lawton, Waite, Tripp, and Ricketson families. Town histories suggest that most of the early residents were resettled from the Portsmouth, Rhode Island area (WHC 1987:20).

The Head of Westport area was undoubtedly occupied by Native Americans prior to the arrival of colonists, especially given the abundant resources associated with the upper Noquochoke and the likely continuity prehistoric period land use in this area (see discussion above).

Early industrial entrepreneurs were drawn to the waterpower generated by the 40-foot natural fall line at the confluence of the Noquochoke River and Bread and Cheese Brook, and by the proximity of east-west land routes and southern water routes. The Head boasted one of the strongest waterpower sources in the town, and was able to support a greater number and diversity of mills than most other sections of Westport (WHC 1987).

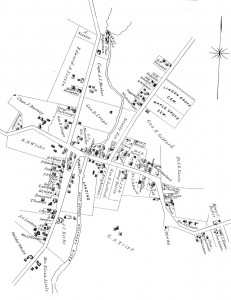

The area became a major milling center despite early setbacks incurred during King Philip’s War. In 1712 or 1713, George Lawton, Benjamin Waite, and John Tripp secured 70 acres of land north of the Head along the river and built two mills, one owned by Lawton on the west side of the river, and one on the east side owned by Waite and later known as Tripp’s or Chase’s Mill (Hutt 1924). The first documented mills appear to have been built in the 1740s, although it is likely that some sort of limited mill activity occurred on the site in the earlier period. Lawton’s sawmill operated for nearly 200 years (WHC 1987).

By the eighteenth century, the Head of Westport boasted a proliferation of saw- and gristmills, a shingle mill, a foundry, and cotton mill. One of the early mills was bought in 1789 by William Gifford, Lemuel Milk, and Josiah Lord. The new owners built a dam and converted the mill for use as a forge (Smith et al. 1976). The complex included a water-powered bellows and trip-hammer (WHC 1987).

The industrial base at the Head evolved over the nineteenth century to include a variety of mills that were used to manufacture hoes, process textiles, turn lathes and grind corn. Manufacturing was not limited to waterpower sources. Davol’s paint mill, for example, was powered by a windmill (Smith et al. 1976:32).

The existing mill infrastructure was also useful for private ventures. In 1795, New Bedford merchant and whale ship owner William Rotch purchased a 20-acre parcel at the Head of Westport that included several existing saw- and gristmills, a working forge (likely the one mentioned above) and blacksmith shop, a coal house, and at least one dwelling. Over the next 50 years, this complex outfitted and repaired Rotch’s vessels (Smith et al. 1976:27).

Smaller mill complexes were located just north of the Head and relied upon the waterpower supplied by Bread and Cheese Brook and the Noquochoke. The Mouse Mill area was originally developed for grinding small amounts of grain (reportedly named for its production of only enough to feed a mouse) and was later converted for use as a shingle mill. The owner, George Gifford, also built a factory in this area that used Gifford’s machinery to shave wagon spokes. The Trout Pond area was developed by the Snell family and supported a carding- and sawmill around 1820 (see discussion above). A leather tannery was located on the property of Charles Baker on Wolf Pit Hill. The mill drew water from a pond and brook to the north that have since been destroyed by a gravel pit (WHC 1987:23–24).

The Head of Westport was also the location of Thomas Winslow’s nineteenth-century shipyard,

which produced several noteworthy whaling ships. Winslow may have acquired the property around the landing from Lemuel Milk, who may have built several small ships at the site to transport his products down the river. Winslow built ships on both the west and east sides of the river at the previously established landings. The Head also served as an important town landing, and during the historic period a great quantity of materials passed in and out of the town through this area, designated as one of several public landings in Westport. One of the largest vessels built at the east landing was the 202-ton Phebe Ann in 1805. The west landing was used to launch numerous one to three hundred-ton ships including the Nye, the President, the Iris, the Alice and the Thomas Winslow (WHC 1987:27).

Unlike most other sections of Westport, the Head was not historically focused on agriculture.

While Westport’s farm products certainly passed out of this area on local vessels, the community was comprised primarily of merchants, tradespeople, and men engaged in shipbuilding and other maritime trades (WHC 1987). After the 1850s, shipbuilding and milling activities at the Head declined and more businesses catered to the area’s prosperous residents. The Head was also known at the time as “Westport Village,” was home to more than 30 sea captains, many of whom were well-off and retired (WHC 1987:10). Late-nineteenth-century shops at the Head included a tailor, cobbler, men’s and women’s haberdasheries, and a cabinet maker. Many of these businesses were established along the east and west landings that had formerly housed the shipyards (WHC 1987).

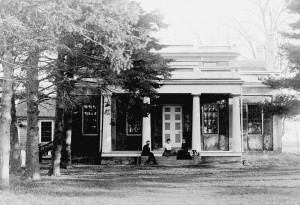

One of the more interesting homes built during the Head’s heyday is the stone mansion located just south of the town landing on the west side of the river. Humphrey Howland built the home around 1830 at a cost reported to be $11,000. The stone used to build the mansion and the surrounding fence was thought to have come from a huge boulder (possibly an outcrop) on a farm a quarter mile away (Worth 1908:21). Town historian Norma Judson noted that the stone was quarried from the Sisson Farm on Drift Road (personal communication 2004). The home retains much of its nineteenth-century character today, with a large landscaped yard area.

As the twentieth century began, the Head of Westport began to lose its former luster. Many of the old sea captains were no longer alive and the community lost its core of prosperous merchants. While Westport Point and coastal sections of town attracted wealthy summer residents, few chose the Head. The increasing popularity of automobile travel and the improvement of roadways also lessened the importance of the Head’s geographic position on the East Branch (WHC 1987). Residential settlement became more focused on middle-class families and the community took on the suburban character it retains today.

The density of industrial operations at the Head necessitated support from shops, taverns, and worker housing. Documented structures in this village included dry goods and general stores, harness and carriage shops, wheelwrights, and an undertaker. Like other areas in Westport, many of these eighteenth- and nineteenth-century businesses were located in buildings still in use today as private homes, offices, and retail shops.

The Head also served through the historic and modern periods as a central community gathering area where public events were staged. Several homes were also located here in the historic period. Many of these took place in the open area known as “the Triangle” at the intersection of Old County and Drift roads, located on the west side of the town landing.