Headwaters to Harbor: Westport’s Heritage of Water

River Journey

(This exhibition was on display 2017-2018 at the Handy House)

What does being on or near the water mean to you?

Freedom?

Fishing?

Escape?

Take a journey through time along our local waterways to discover a place far from the serene retreat that we experience today — a river that was a bustling workplace, a secretive place of hiding, and a resource that was harnessed by an entrepreneurial spirit.

Next time you spend a day on the river or on the beach cast your thoughts back a few generations to a time when these flowing waters signified livelihoods, fortunes won and lost, commerce, risk, adventure, danger, and the watery route— to exotic lands…

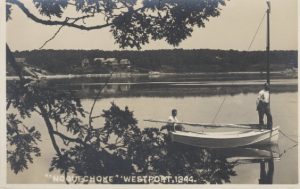

The Noquochoke

The East Branch is sometimes referred to as the Noquochoke, a Native American description meaning “the land at the fork.”

The Acoaxet

The West Branch is sometimes known as the Acoaxet, a Native American place name meaning “the land on the other side of the little land.”

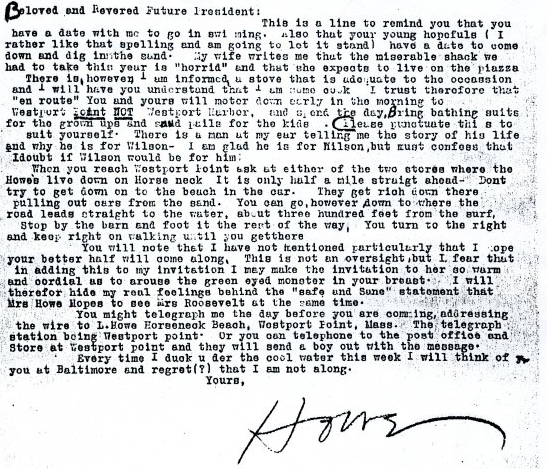

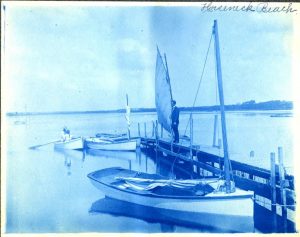

HORSENECK BEACH

FDR stayed here!

Franklin Delano Roosevelt came to Westport in 1924 and 1925, staying for several weeks with his close adviser Louis McHenry Howe in a cottage nestled on the edge of the dunes at the far end of West Beach. FDR spent his days sitting in a tent at the edge of the ocean, building model boats, and “working” on a movie script. In the afternoon FDR entertained friends with stories whilst sipping an orange blossom cocktail.

The community of East Beach

Boasting a Catholic church, a post office, hotels, stores and many summer cottages, this community was wiped out by the 1938 hurricane.

(WHS 2005.081.267)

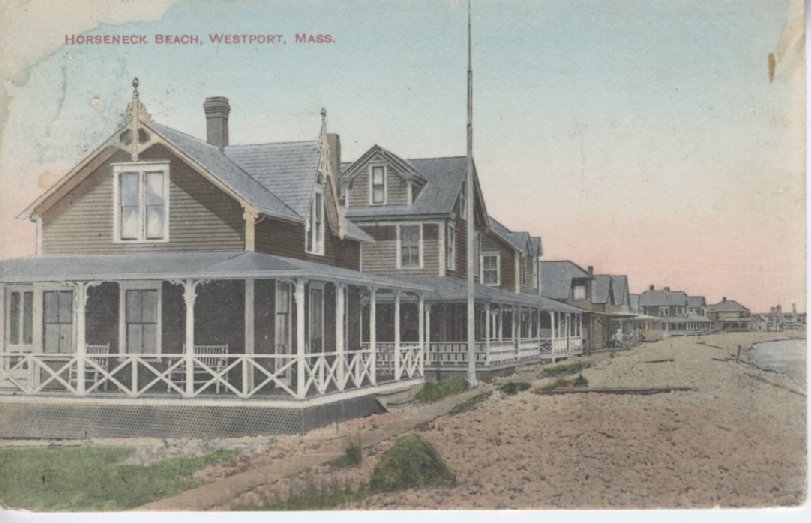

Cranberry bogs on Horseneck

Cranberries grown on Horseneck were said to be much better than those grown inland. An 1860 record lists “good” cranberry lots for sale at Upper Horseneck for $5 to $20 per acre. Several barns and cottages were constructed to support the industry. One newspaper article reported that two enterprising citizens of Westport “built a lodge where they have cooking utensils, library and other things to render it not only profitable to themselves, but a pleasant place of resort for those who visit the Horseneck house, and others. They have a large boat of easy draft, and can approach within a few feet of their houses on the bank surrounded with woods.”

Everyone participated in the cranberry picking, especially those who lived at the Point. Local schools closed for 2 weeks each September to allow pupils to pick berries. A contemporary account describes the scene:

“In the autumn it was fun to go to the cranberry bogs along the north shore of the sand hills and watch crowds of Westport Pointers at work picking — the more so because we could call them all by name.”

(WHS 2009.004.006)

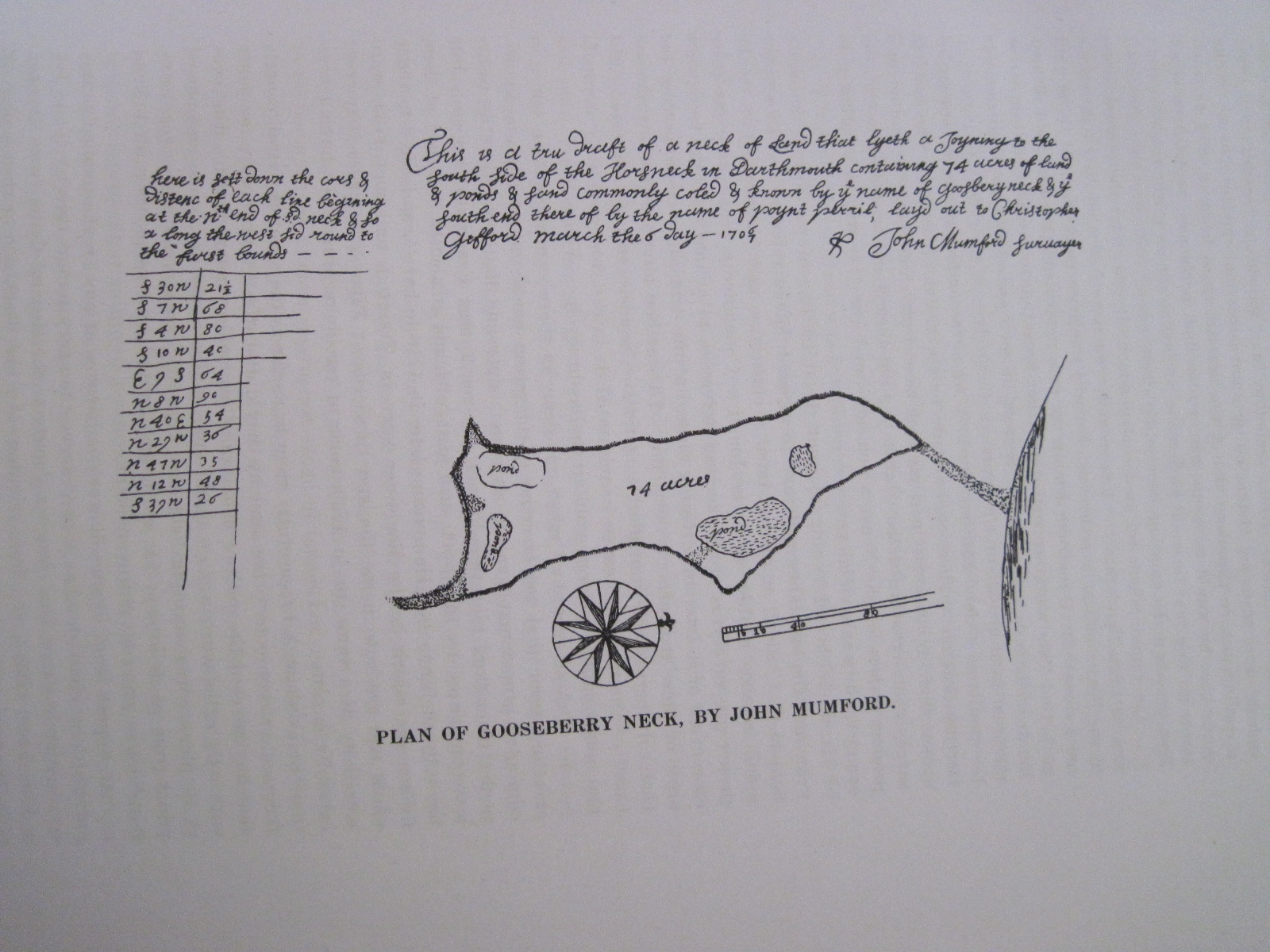

GOOSEBERRY

Point Peril

Even before the elevated causeway was constructed in 1924, a natural causeway allowed summer visitors and residents to walk to the spit of land at low tide. This was a perilous undertaking, and visitors were often trapped when the tide came back in. A newspaper report dating from 1861 describes the predicament of a farmer:

“Yesterday, Mr. Thomas Allen in Westport, with his team, consisting of a yoke of oxen and a horse, attempted to cross from the main land to Gooseberry Neck, when he was overtaken by the waves and tide, and placed in a most perilous situation. The oxen by some maneuver turned their yoke and got rid of the wagon or cart, and finally swam ashore. Mr. Allen, who was unable to swim, managed to get hold of the horse’s head and hold on until he was rescued in a completely exhausted condition. The horse was drowned by having his head held under water by Mr. Allen. The cart went to sea.”

(Plan of Gooseberry Neck 1707)

The Army and Navy took over Gooseberry Neck during World War Two. The government built an observation tower and barracks, disguised as farm buildings.

Shipwrecks

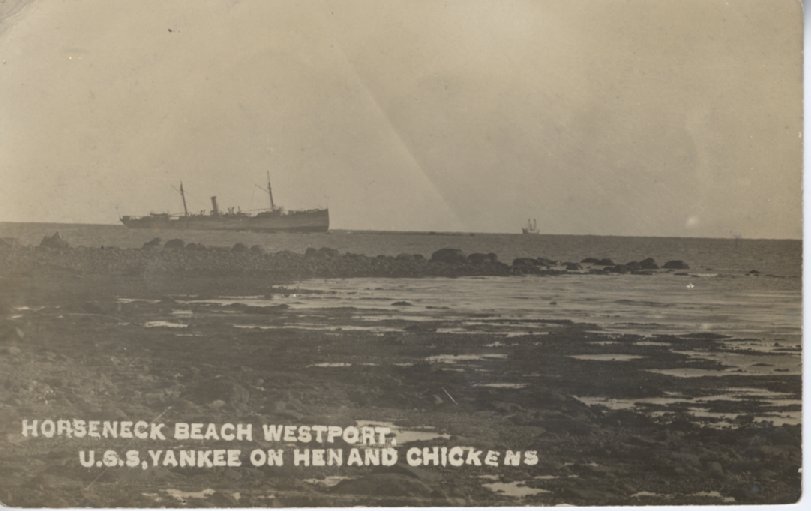

In September 1908, the USS Yankee while on a training excursion for the U.S. Navy, encountered a dense fog, compounded by smoke from nearby forest fires in Buzzards Bay. With obscured visibility, Yankee ran aground onto the rocky reef at Hen and Chickens in Buzzard’s Bay during dense fog.

In 1920 USS Yankee was determined to be a navigational hazard to shipping and was demolished with dynamite by the U.S. Navy. Today, large pieces of Yankee’s hull cover a wide area and can be explored by divers.

(WHS 2005.081.305)

“Heave, haul and pull”

Navigating Westport harbor was not an easy feat for many of the whaleships, particularly the larger vessels. Ships kedged their way out of the harbor by throwing out the anchor and then pulling in the line, repeating this operation so that the ship moved slowly out to the open sea.

A contemporary account describes how whaleships entered the harbor:

“When a whaleship returned from a voyage, its masts were sighted above the sand dunes, and the old pilot, Clark Tripp, would meet the ship. Waiting until the tide and wind were right, he then sailed her right to the wharf, fully loaded” (Abbott Smith).

HARBOR

Buried treasure on Liniken Island

Tidal islands such as Liniken Island were used as pasture for cows and sheep. Liniken Island contained 12 acres in all, 6 acres of upland portion used to grow crops such as corn and pumpkins and 6 acres of marsh. An unconfirmed story of unknown origin records that Captain Kidd buried his treasure on this island!

An old cellar or a horse’s neck?

The name Horseneck may be derived from the Native American designation “Hassanegk”, meaning “a house made of stone.” One such structure existed somewhere in the vicinity of the beach, described as an “old stone cellar, probably an excavation made in the hill side, lined with field stone and roofed over.” This structure was probably destroyed by coastal storms.

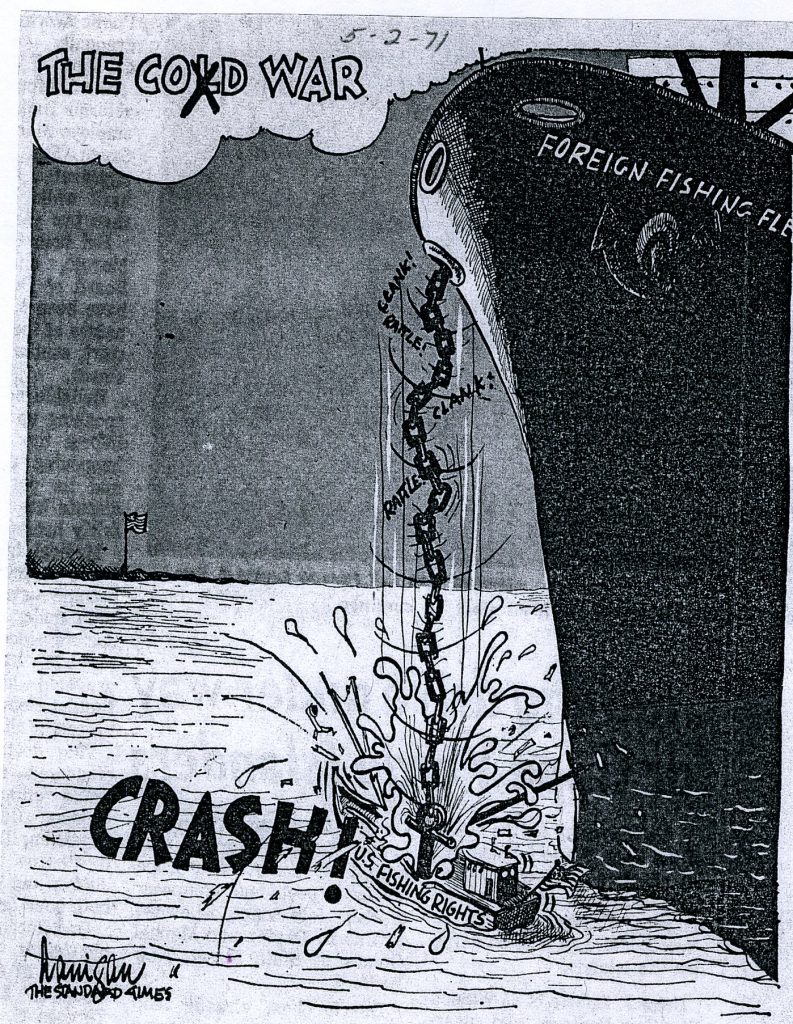

The Lobster War

The Prelude Lobster Corporation adopted a revolutionary approach to lobstering which enabled fishermen to fish in deep water far off shore and to tap into the abundant population of lobsters in the Continental Shelf. In 1971, following a controversy over damaged gear, Prelude found itself at the center of the “Lobster War” with the Soviet Union. This peaceful international incident sparked the move towards the 200-mile zone around domestic shores that protected U.S. fishing vessels from encroachment by foreign fishing vessels.

Cherry and Webb

Cherry and Webb Conservation area named after one-time owners Oliver Cherry and Frederick Webb of the department store fame.

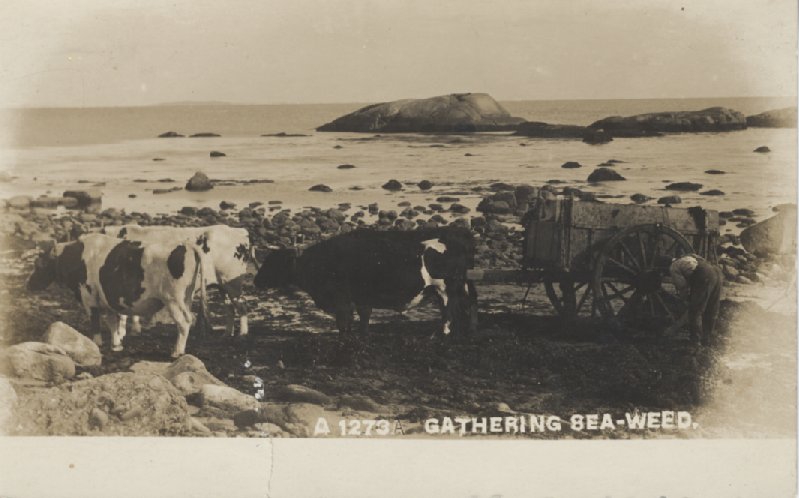

Seaweed

Seaweed was a sought after commodity, as it was used as fertilizer and as insulation. The town issued permits for seaweed collection. This letter to A.J. Manchester grants permission to “land seaweed” from Gooseberry Neck to Reed Road as long as it didn’t “interfere with the public travel, or become a nuisance by creating an offensive odor.”

(WHS 2006.036.203)

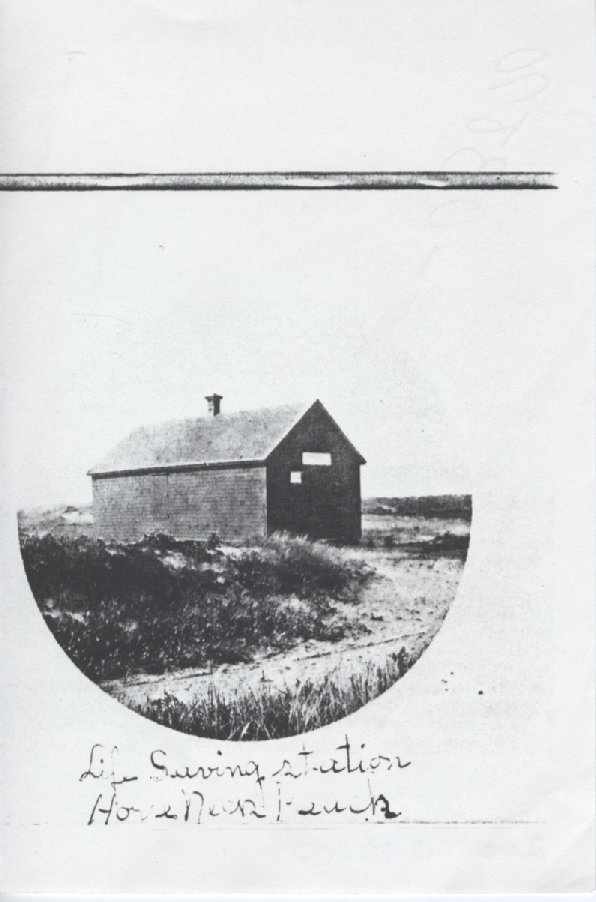

The Horseneck Point Life Saving Station

The Horseneck Point Life Saving Station dates back to 1888, when it was built by the Humane Society of Massachusetts), originally at the Westport Harbor entrance on the west end of Horseneck Beach. It was moved to its present location on East Beach in 1894. Today it is preserved as a significant survivor of our maritime heritage and is now open to the public.

(WHS 2006.042.027)

Tripp’s Boatyard

Tripp’s Boatyard founded by Frederick Tripp in the 1920s was originally located near the high school on Main Road. The boatyard moved to Horseneck in 1933.

(WHS 2007.050.101)

WEST BRANCH

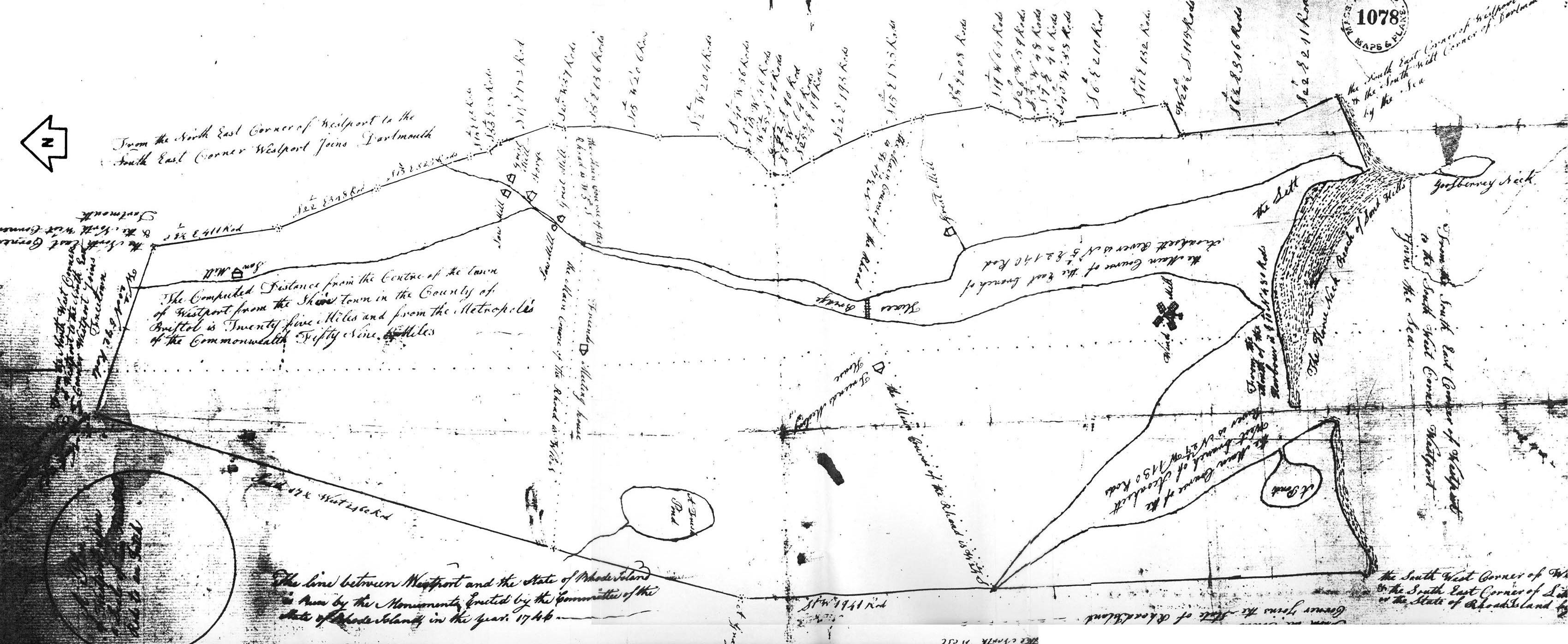

18th century maps and charts reveal a familiar coastal landscape. Both branches of the river are often referred to as the Acoaxet River. Sometimes the East Branch is referred to as the” Noquochoke”, a Native American description meaning “the land at the fork.”

The West Branch is often known as the “Acoaxet”, a Native American place name meaning “the land on the other side of the little land.”

(1795 survey of Westport by Zadock Maxfield, Massachusetts State Archives)

Fortifications along the West Branch

Fortifications along the West Branch

18th century coastal survey maps indicate the presence of defensive fortifications or structures of some kind between Cockeast Pond and Richmond pond.

(Blaskowitz Map of Narragansett Bay, 1777)

Westport Harbor Aqueduct Company

Water quality at Westport Harbor varied. After the 1938 hurricane residents complained of salt in the water as well as solid items. One resident claimed to have found owl feathers in the water!

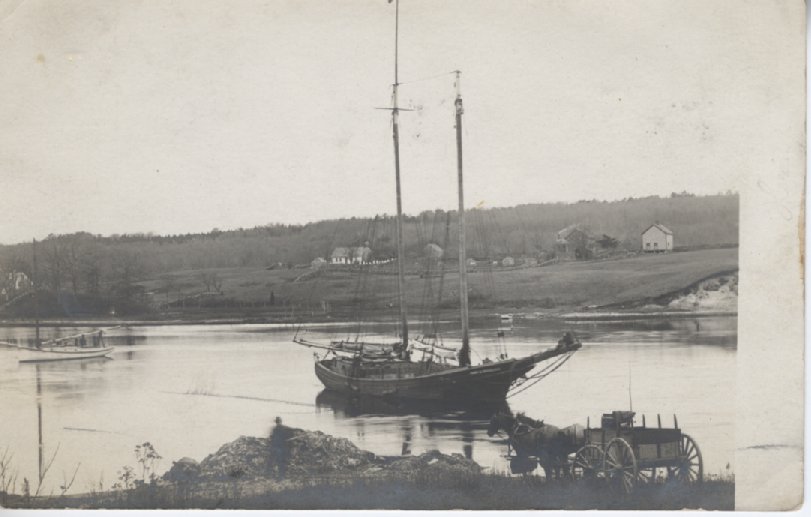

Wharves

By the early 1800s, wharves were in place at the mouth of the West Branch.

(Map of Westport, 1831)

Cockeast Pond

The 1795 map depicts this pond as an open embayment connected by a channel to the West Branch. The 1830 map shows the pond closed off from the inlet but referenced as a salt water pond. This area was probably highly attractive to Native American populations.

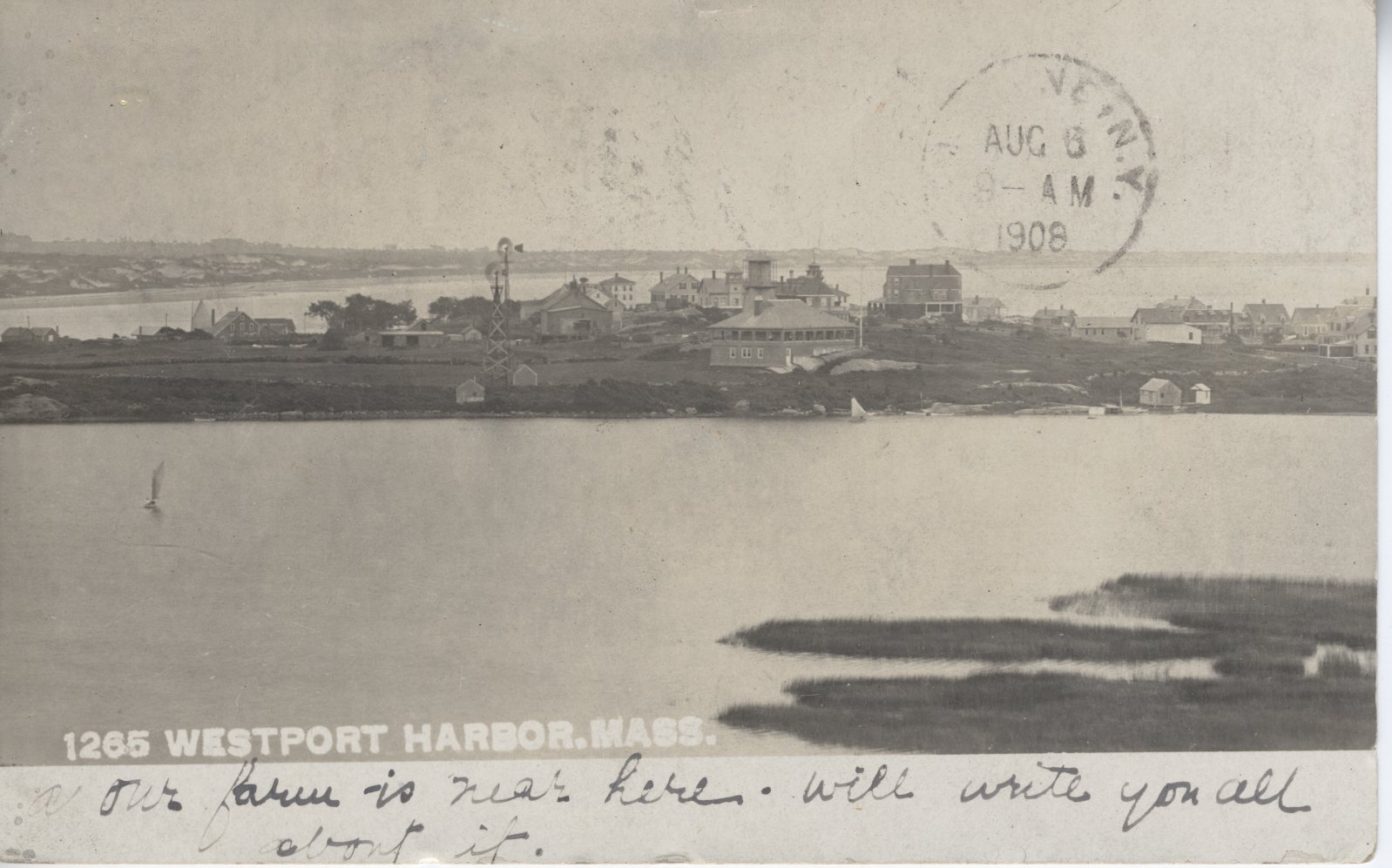

WESTPORT HARBOR

Sowle’s Hotel

Perched at the mouth of the Westport River, Sowle’s Hotel was built in 1873 and became a magnet for the summer visitors, who were drawn by the excellent striped bass fishing.

(WHS 2005.078.205)

The Casino

Built at the southeast corner of Cockeast Pond in 1903, the Casino hosted Saturday night dances, theatrical performances, Sunday morning church services, clambakes and summer socials.

(WHS 2007.050.050)

The Pavilion

Located on the same site as Elephant Rock Beach Club, the Pavilion was a popular bath house, built in 1894 and destroyed by the hurricane of 1938.

(WHS 2003/037.002)

Charlton’s Wharf

Old timers recall retired sea captains bringing their boats over from the Point to Charlton’s Wharf to pick up passengers for a day of fishing.

Harbor windmills

“When I lived at the harbor, they got their water by windmills. The water system at the harbor was made of cypress wood. It served all the summer houses” (Archer Tripp, born 1911).

(2006.036.123)

Point of Rocks or the Knubble

The Point of Rocks marks the entrance to the Westport Harbor. The spindle was erected by Hale Remington.

WEST BRANCH

The Great Island Mission of Holy Spirit

The charismatic leader of a French Canadian religious sect found his way to Westport in the 1920s, settling on the remote Great Island. Here they erected a meeting hall and an apartment building for members on the shore. Although the sect asserted that ultimately it would rule the whole United States, the society remained benign in nature. Fortunately, its presence in Westport was short-lived as the leaders, facing accusations of fraudulent behavior, quickly moved on to other parts of the country.

Taber’s Mills

Adamsville was originally known as Taber’s Mills. Early settlers were quick to realize the area’s potential and dammed the pond to maximize its waterpower. By the early 18th century Philip Taber operated a water powered grist mill. A saltworks is reported to have been in operation at the Head of the West Branch near the tidal wetlands.

(Map of Westport, 1871, WHS 2009.037.053)

Ice harvesting V ice skating on Adamsville Pond

Over the years the pond has also provided the community with both the ice to preserve their food before the advent of refrigerators and a wintertime recreation area perfect for skating. Harvesting pond ice was big business from the 1800s to mid-1900s, although skaters were very unhappy when ice harvesting interrupted their wintertime fun on the pond. Parts of an old road called “Ice Avenue” used during the ice harvest are still visible today.

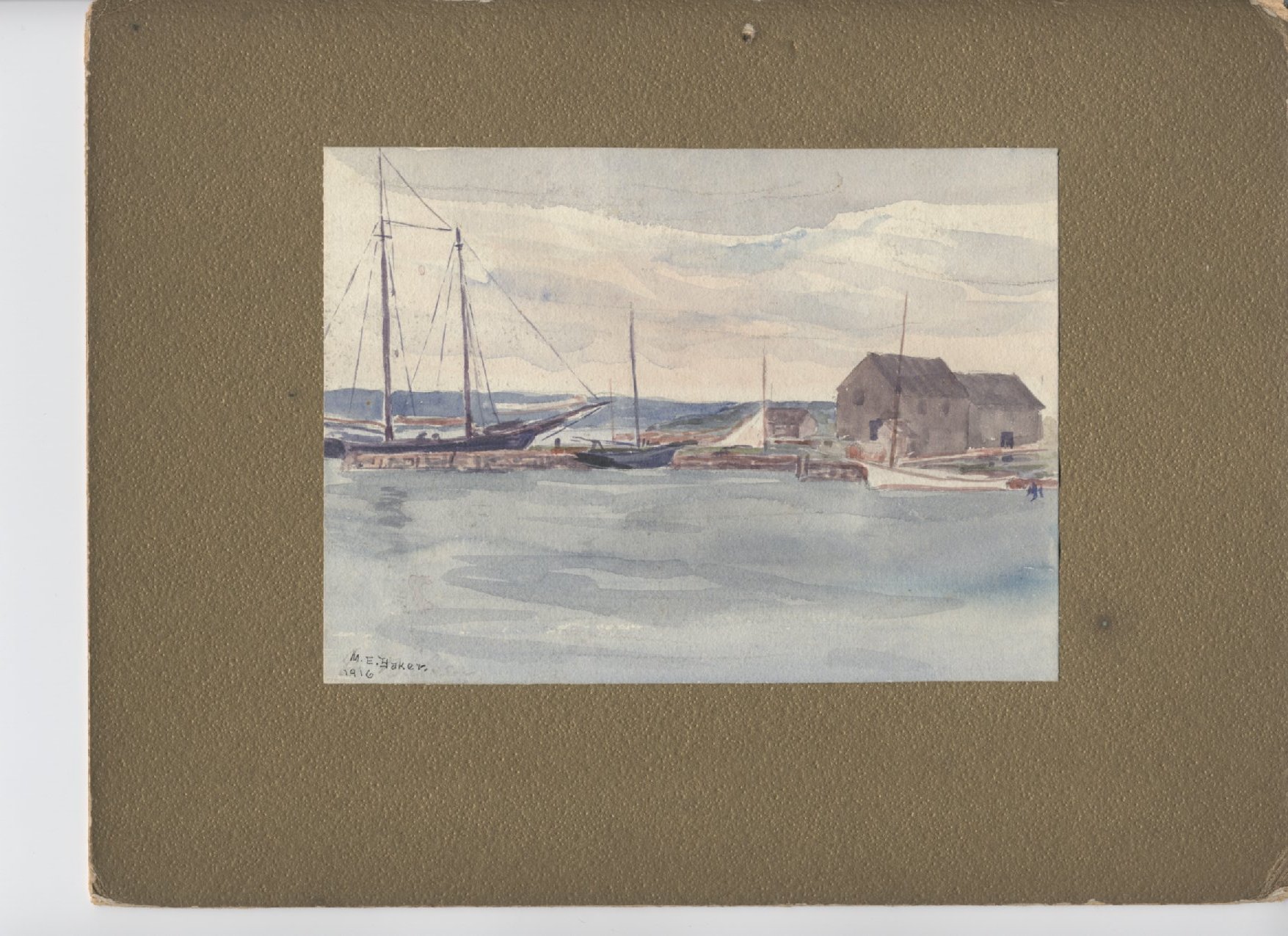

WESTPORT POINT

A community defined by its location, the Point was the center for maritime activities. Beginning with the codfish industry in the 18th century, the Point was transformed by whaling activities of the 19th century. Blacksmiths, coopers, ship carpenters, sail and rope makers, saltworks and sawmills converged at the Point to service the needs of incoming and outgoing ships. The Point also served as a temporary storage area. In 1860 1,100 barrels of sperm oil and 250 barrels of whale oil were stored at the docks.

(Watercolor by Mercy Etta Baker WHS 2005.083.003)

The Sisson and Allen Shipyard

Frank Sisson and Eli Allen built several whaling vessels here, including the Kate Cory and Mermaid.

Westport Point Bridge

The Point Bridge was completed in 1894. The bridge rotated to “open” for vessels traveling the East Branch of the Westport River. Four-to-six men walked in a circle pushing a long wooden pole attached to a metal key to operate the gear system which swung the “draw” span open. However, as traffic jams plagued the Point and with the construction of Route 88, the bridge was torn down in 1963. The Point, a pristine historic district, has since become a secluded and sought-after location to live.

(WHS 2005.081.223)

Saltworks

According to one historian, “there must have been a merry whirl in progress along the shores of Buzzards Bay early in the century.” Windmills and “mushroom villages” of saltworks lined the rivers. Salt manufacturing supported the commercial fishing fleet. It was essential for the preservation of fish and meat. These sites included evaporative works and windmills that moved water from the harbor through a system of pipes to large drying areas. Saltworks were located north of Woods Point and on the west bank of the East Branch, opposite Great Island. It is also thought that saltworks may have been located on Horseneck Beach and at Adamsville.

(Detail showing the Acushnet River, Purrington-Russell panorama courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum)

Gun-a-bit

About a century ago there were a number of hunting and fishing camps at various waterside locations in town. One such was subsequently converted into a dwelling. The names of the buildings at the camp may prove of interest. The camp itself was called “Gun-a-bit,” the main house was called “Grin-a-bit,” the kitchen was called “Grill-a-bit,” and the outhouse was called “Grunt-a-bit.”

Waterway

Both branches of the Westport River served as major transportation corridors. The town built and maintained fords, ferries, driftways, landings and bridges to improve these networks. Through the centuries, waterways brought supplies such as coal, molasses, and seaweed upriver and carried produce and materials to urban markets along the east coast.

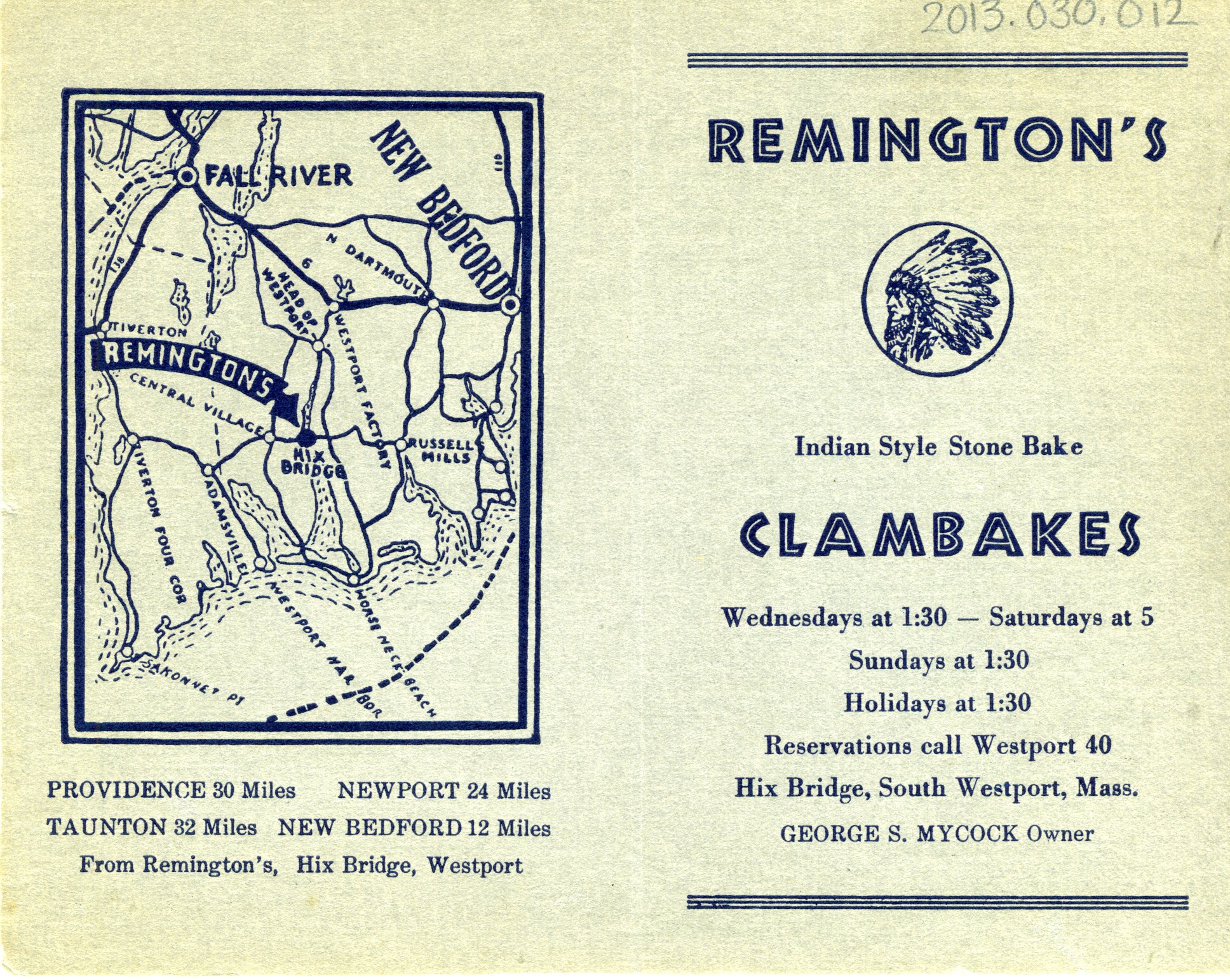

Hix Bridge, otherwise known as “a common nuisance”

Built in 1738, the bridge replaced what may have been a chain ferry across the river. The bridge was considered by some to be “a common nuisance” as it obstructed the waterway between the Head and Westport Point.

Tradition has it that one of the chief forms of entertainment for young men used to be to race their horses down the hills on either side of the bridge, both being steeper than at present, and at such a rate of speed that the gatekeepers at either end were afraid to keep the gates closed for fear of a terrible accident. Thus, the gatekeeper would open the gate and the travelers would pass over the bridge without paying a toll.

What did it cost to cross the bridge?

Single passenger, 1 penny

Every horse and man, 2 pence

Every score of sheep or hogs, 5 pence

(Simple cable ferry, Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1939)

Remington’s Clambake

Remington’s, located at the western end of Hix Bridge, was known for its clambakes in the early 1900s.

Tripp’s Wharf

Sloops sailed from Tripp’s Wharf to the West Indies, bringing molasses back to Westport Point.

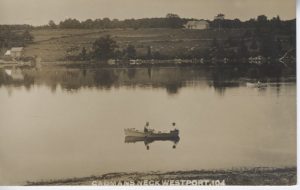

Cadman’s Neck

This small promontory of land edging into the east branch of Westport River was once a hub of activity, a place where thousands of people would gather to participate in religious camp meetings. Given the specific logistical requirements for a successful camp meeting, Cadman’s Neck was a natural choice, offering good drinking water, pasturage for horses, shade for the audience, a forest to screen the meeting from the world, and access by water.

(WHS 2006.027.063)

Head of Westport

Early industrial entrepreneurs were drawn to the waterpower generated by the 40-foot natural fall line. By the 18th century the Head of Westport boasted a proliferation of mills including saw mills, grist mills, shingle, foundry and cotton mills. By the 19th century, a variety of mills existed to manufacture hoes, process textiles, turn lathes and grind corn.

(Detail from map of Westport, 1831)

Tannery

A leather tannery was located on Wolf Pit Hill drawing water from a pond and brook that was probably destroyed by the gravel pit. The tanning process required large amounts of water to soak and wash hides.

Mouse Mill

Mouse Mill brook supported several mills. The brook’s name is reported to be a reference to one of the smaller gristmills that produced only enough grain to “feed a mouse.”

Gifford Rule Factory

This site began as an iron mill. The Gifford Rule Factory, established in the 19th century, produced high quality wooden rules.

Trout Pond

Created as a mill pond on the Bread and Cheese Brook, it later became the location of Snell’s Mill Site which included a carding and sawmill.

Westport Factory

This location at the confluence of the Bread and Cheese Brook, East Branch and Noquochoke Lake has been a magnet for mills since the 1700s. A map dating from 1795 shows several saw mills in this vicinity. The Westport Manufacturing Company, founded in 1812, produced carpet warp, twine and mop yarn from scrap materials obtained from the Fall River mills. The mill included 1400 acres, 38 buildings, and a village for employees.

(WHS 2012.017.035)

Lake Noquochoke

This lake was created to allow the Westport Factory to run by water power about 9 months of the year.

Bread and Cheese Brook

How did it come to be called Bread and Cheese Brook? According to local lore, in 1776, a company of Revolutionary War soldiers on a reconnoitering expedition for Lafayette, stopped along the banks of this stream and ate bread and cheese and drank of its waters.

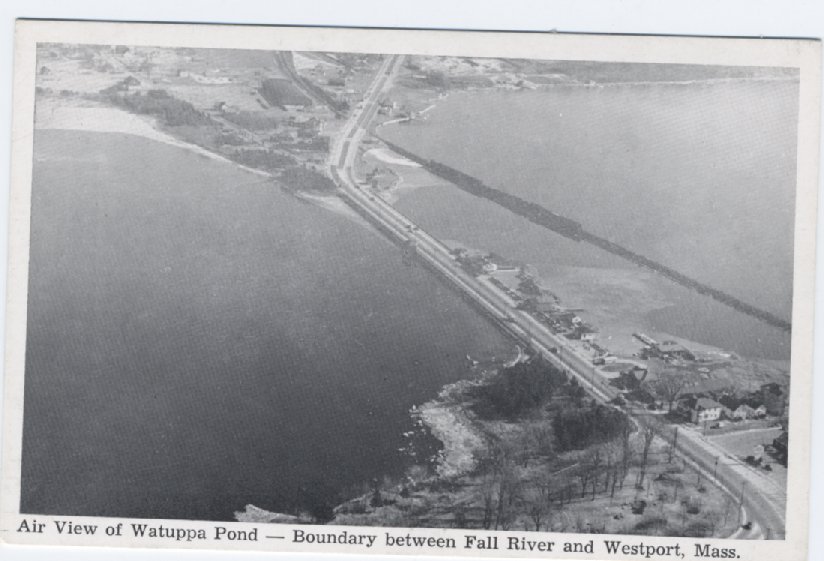

Watuppa Pond derives its name from a Native American word meaning “place of boats.”

Originally one large inland lake, more than 7 miles long, the Watuppa Ponds powered the mills of Fall River. The ponds lie partially within the bounds of Westport. By 1840, the battle for water rights and to protect the ponds as a drinking water supply for Fall River had commenced. Competing uses of the ponds for swimming, boating, logging, freight hauling, sand and gravel operations, and ice cutting extended the battle for the ponds for many decades.

Lassonde Ice House

Several ice houses were located on the North and South Watuppa Ponds. The Lassonde ice house was located near White’s Restaurant, on the shoreline where the ice froze early to the desired depth of at least 8 inches. Cutting ice began in January with some urgency in case of sudden rise in temperatures. Within three weeks, they produced enough ice to last an entire year. By the 1940s, as home refrigeration became more common, the ice industry began to decline. Many ice houses burned down and by 1950 nearly all of the ice houses around Watuppa had disappeared.

(WHS 2006.042.287)

The Narrows

At one time a foot bridge of stepping stones ran across The Narrows. By 1827 the Watuppa Turnpike connected Fall River to Blossom Road in Westport.

Boating and ice skating on the Watuppa Ponds

Two boathouses, Napert’s and Robillard’s, became the center of activity on the Watuppa Ponds in the 1930s and 1940s. Both provided rowboats for rent, charging 25 cents per hour or $2 for the day. Visitors were transported to their lakeside cottages on one of five ferry boats: The Greyling, the Recreation, the Silverwave, the Fireman, and the Lead ‘Em All.

On a clear Saturday night, over a thousand skaters flocked to the Narrows entertained by music and illuminated by spotlights provided by the boathouses. By the early 1960s as the state took control of the area to build route 195, the boathouses were knocked down and middle pond was filled in.

Adirondack Grove, a former picnic grove on the eastern shore of the North Watuppa Pond

Blossom Brook, drains into a swamp east of Blossom Road. Early settlers claimed its water “possessed wonderful medicinal properties, and was sought after as a sure cure for any and all diseases.”

Native Americans

In 1602, Bartholomew Gosnold reportedly landed at Gooseberry Neck where he encountered natives bearing gifts of “skins, tobacco, sassafras root, turtles, and wampum.” Both branches of the Westport River were the homelands of the Acoaxet Native American group. This area was probably intensively used as a marine resource, planting grounds, and land and water transportation routes.

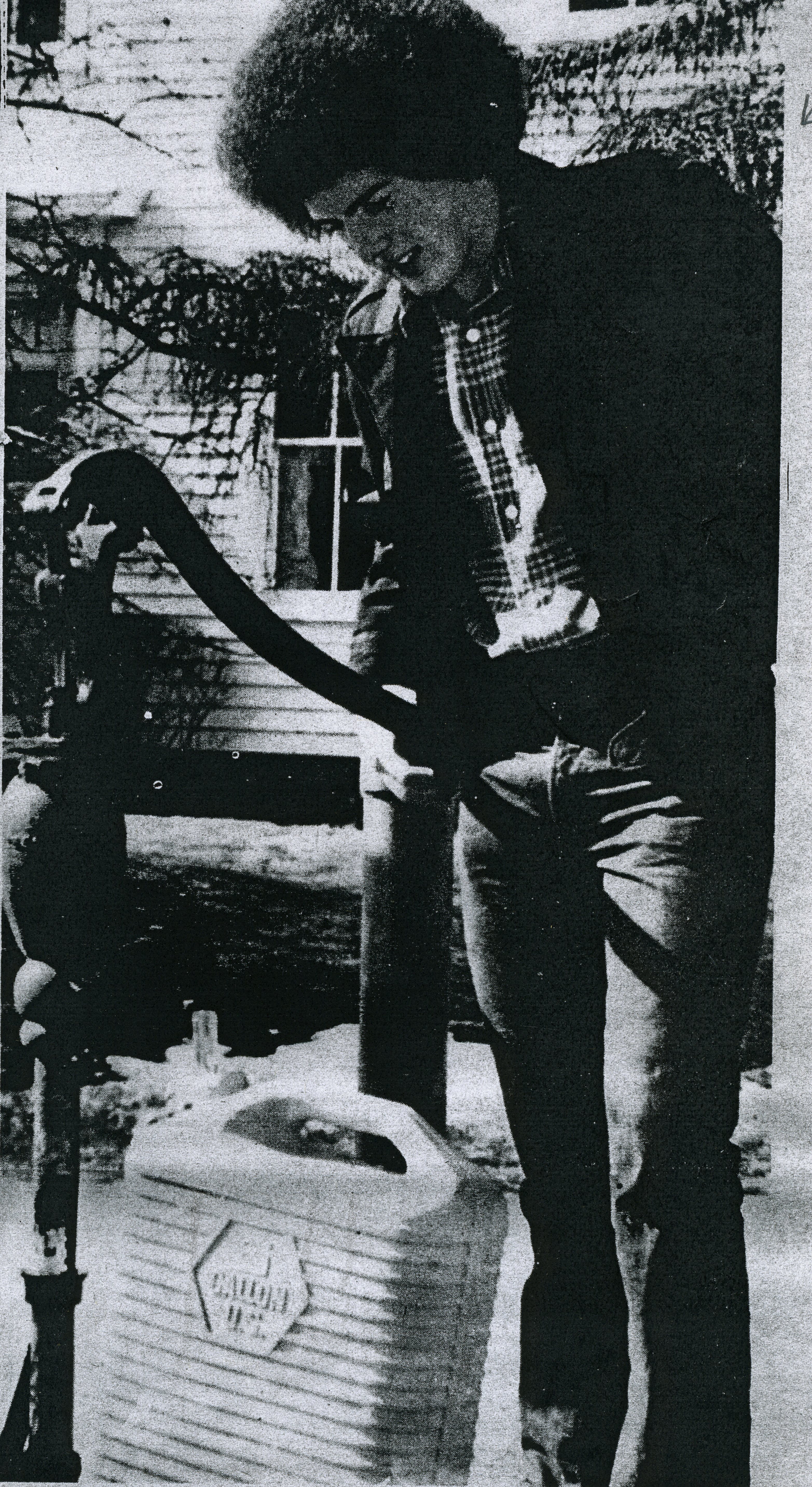

The Town Pump

The Town Pump, once located at Central Village, had the reputation of providing the sweetest water in the area. Jeffrey Burns made a weekly trip from Fall River to fill seven gallons worth of containers claiming that there was too much chlorine in Fall River’s water. The pump remained in use until the 1980s when, due to contamination, over usage, and traffic congestion, the well was closed.

The Sharpie

The flat-bottomed rowboat or sharpie was the indigenous craft along this stretch of the coast. According to one account from the early 1900s, sharpies made trips down the river to Horseneck and came back to the Head of Westport loaded with seaweed or salt marsh hay which was unloaded on the public landing opposite the Bell School and sold to farmers.

In the late 19th century, saltmarsh hay was a vital crop for local residents as it was utilized for forage, bedding for animals and is still utilized for mulch in gardens. Hay was cut by hand using a scythe. It required the strength of two strong men armed with a double-sided hay rake for making a large pile upon the marsh to harvest later. Farmers often were forced to wait until the marsh was frozen in order to bring hay back to the farm.

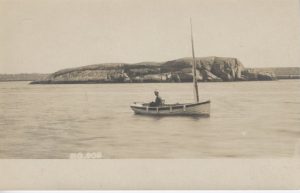

Boating

“I never saw so many ships on the horizon, so thickly clustered off Cuttyhunk that they seemed to form another island. The two-masted Mary Douglas and John G. Pettis came regularly into our harbor and on occasion up to Adamsville often with serious problems of wind and tide.”

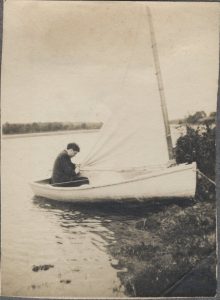

Catboats

It was the age of the catboat, a proud fleet of which owned by individual Point sea captains, made daily fishing trips on the ocean all summer. It was a gallant sight, particularly on a blue day of good visibility to watch them proceed to sea, single file, in the morning, and come back in the same fashion in the afternoon.

“One of the events here was watching the catboat fleet – on any good day – going out through the Harbor off to Gooseberry Neck and Vineyard Sound – to the ocean. Then you’d see them coming in. They had to make it to the Northwest, and then turn to the Southeast. There were no trees on this hill at that time. We’d go up to the top of the hill and see everything coming over the horizon, almost to Sakonnet Point and Buzzards Bay, and off to No Man’s Land. We’d watch the schooners and tramp steamers go by. Once we saw the Thomas W. Lawson, that seven-masted schooner, go by. Once we saw a hotel going by on a barge.”

Water hole springs

“I love to find water holes springs…if you follow the brooks you will find springs…in one place on Drift Road there are fifteen springs.”

Eeling

“Well, you have a spear, it goes right into the eel and you hook him and you can’t get it out. Then you go punching for more. The eels go into the mud at night” (Julius T. Smith).

Ice skating

“There was a little pond across from the schoolhouse—that’s where we went to skate. The pond wasn’t deep enough to swim in. In those days, the winters weren’t like now. I saw the Westport River frozen clear down to the opening of the harbor. We’d have five or six weeks at a time when it was below zero and we’d have oxen on the rivers” (Milton Borden).

Ice skate? Yes, down on the pond at the harbor. There’d be fifty of us sometimes. We had ice boats – three ice boats where you’d sail all day if you wanted to. That was the most fun of all. Yes, there ain’t no more of that any more – ain’t no ice. Ice would be anywhere from 12 inches to 3 feet thick (Everett Coggeshall).