The Allen’s of Horseneck Beach in the 1900s

Posted on December 27, 2022 by Jenny ONeill

By Donald M. Allen (March 13, 1926 – December 17, 2022)

My name is Donald Macomber Allen, and I was born in Fall River, Massachusetts in 1926. As my name indicates, most of my ancestors were from southeastern Massachusetts, and some were born in Westport, MA. From about 1911 to 1964, some of my close relatives owned property or lived at Horseneck Beach and much of my early life was spent there.

Donald Macomber Allen, circa 1936

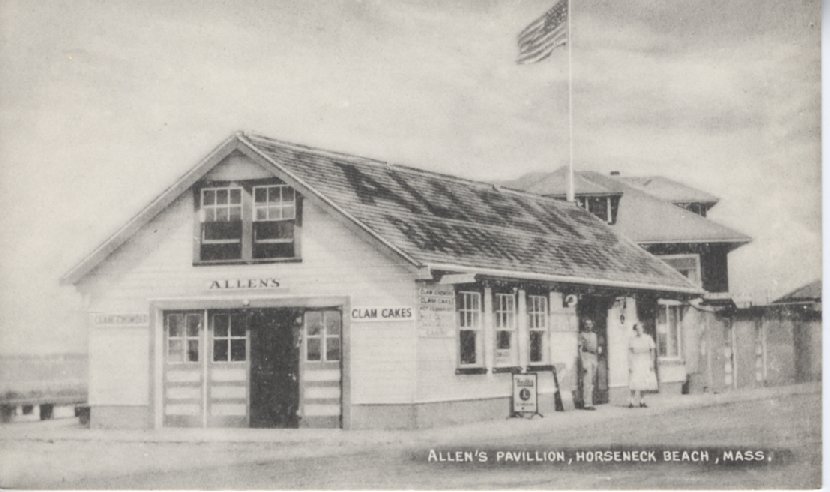

My grandfather, Alton Alfred Allen, came from Fall River, MA. During his working life he had been a farm manager, a carpenter, and a contractor. He used his horses and wagons to transport large quantities of sand, gravel, and other materials to build roads and parks for the city of Fall River. In 1911, he and my grandmother, Ella Mosher Allen, bought property at Horseneck Point, often called Allen’s Point. Allen’s Point is located at the convergence of East and West Horseneck Beaches. About 1913, the A.A. Allen house (current address 151 West Shore Road) at Allen’s Point was built and named “Lookout” because of its commanding view of the surrounding waters and beaches. Allen’s Pavilion was built by my grandfather (A.A. Allen) and my father Alton Ward Allen, and construction was completed about 1920. The Pavilion was adjoined to the house. When my grandfather died in 1923, my grandmother became sole owner of the house and Pavilion.

Alton and Elizabeth Allen

My father, Alton Ward Allen, from Fall River, and mother Elizabeth Bushnell Allen, from Fairhaven, were both U.S. Navy veterans of World War l. The A.W. Allen house (current address 148 West Beach Road) was built in 1920 on the west side of West Beach Road, overlooking West Beach, about four lots north of the A.A. Allen house.

I had two older brothers, Stanley Ward Allen and Stillman Bushnell Allen (twins) who were born in 1920. Stillman died in 1922. I was born in 1926. We lived in the West Beach House in the warm months when the Pavilion was open for business, until 1930.

In the 1920’s the Pavilion was managed by my father, Alton W. Allen, and his younger brother Stanley Dean Allen. In its heyday in the 1920’s the Pavilion had a large number of customers, attracted a variety of products and activities. This accounted for its early success as a business venture, until the beginning of the Depression in 1929. Surf bathing was the major attraction, and this required many rental bath houses for bathers to change in and out of swimsuits. To facilitate the rapid movement of crowds of bathers into the ocean, the Allen’s developed a unique system by which customers could change clothes in a bath house and have their boxed clothing stored temporarily in another building. By this method, each bath house was immediately available for another paying customer, a number of who could be rapidly cycled through each bath house. This system was later adopted by bathing facilities elsewhere in the United States.

Allen’s Bathing Pavilion

In addition to surf bathing facilities, other components of Allen’s Pavilion were a restaurant, a hotdog/hamburger/soft drink stand (a small glassed-in structure connected by a breezeway to the south end of the main restaurant), a grocery store, a rental automobile parking lot, and access to the beach and surf bathing. Also, surf boats were rented to customers. The so-called surf boats were not true boats but were more like a surfboard. They were about five and a half feet long, two and a half feet wide and six inches deep, and vertically tapered at each end so they could easily ride in the breaking surf. These surf boats were designed, built, and patented by my grandfather, A.A. Allen, in 1919. Postcards from that era showed them being used in the ocean at the Allen Pavilion.

The Allens also owned an ice pond. Ice was used in the restaurant and block ice was sold at the grocery store and ice and groceries were delivered to beach residents daily. The ice pond was originally a shallow pond or slough a few hundred feet northwest of the junction of East Beach and John Reed roads. My grandfather hired a Westport farmer with oxen and a scraper to deepen the site to hold more water for producing ice. One winter, about 1919, a crew from Cuttyhunk came by Horseneck to cut ice at Allen’s ice pond. Among the crew was Irwin Winslow “Coot” Hall, who later became a famous striped bass guide. Many years later (1951) another Cuttyhunker, Virginia Carlyle Stetson and I were married.

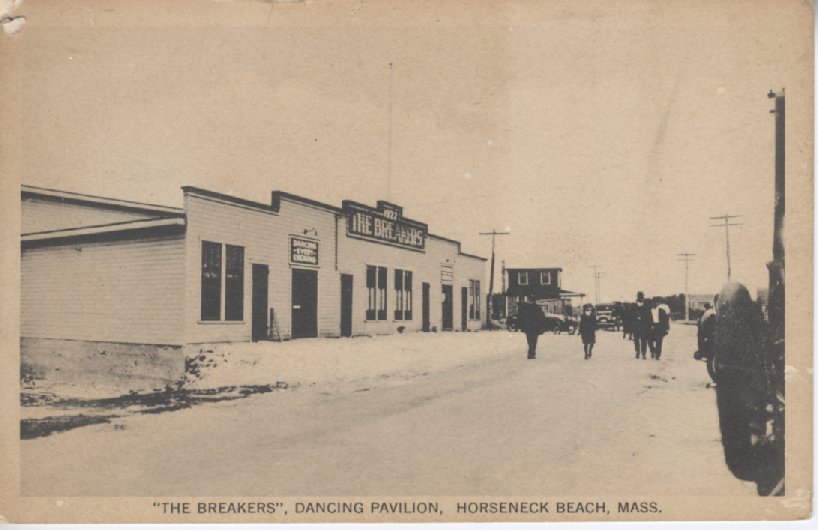

The 1920’s location of “The Breakers” at Horseneck Beach seems to be unknown, according to reports I’ve seen. I remember “The Breakers”. It was located on the east side of West Beach Road, directly across the road from the A.W. Allen House. It was a roller-skating rink by day and a dance hall by night. I can recall that in the daytime, customers roller skated to the tune of “Valencia” which was imprinted on my mind at an early age because it played almost endlessly. At night the building became a dance hall. One of the dance hall band leaders was Lou Breeze, who later became well-known throughout the music world. “The Breakers” burned down one summer night in 1928. Although I was less than three years old, I remember seeing from our front yard across West Beach Road the firemen silhouetted against the flames as “The Breakers” disappeared into the ashes.

The Breakers

In the late 1920’s, when I lived there, the beach in front of the Alton Ward Allen house on West Beach was sandy. Any rocks that did occur there were small and scattered. I was often exploring the beach and was intrigued by the sea clams, baby crabs, and other marine organisms I found near the oceans edge. Sea clams were abundant in the waters off West Beach. The Allens went into the surf and dug clams with potato rakes putting their catch into burlap bags, slung over the shoulder. These clams were used to make clam chowder and clam cakes sold at the restaurant.

Allen’s Pavilion

Before the causeway to Gooseberry Neck was built, the Neck was connected to Allens Point by a sand bar. Nearby was Bar Road, probably named for the sand bar. The Neck was not easily accessible across the bar, except at low tide. In the early 1900’s large rocks were placed along each side of the bar, but the causeway was not completed until 1924. Years later, rocks (cobble size and shape) began to appear on West Beach, gradually accumulating from Allens Point northwesterly toward the Westport Harbor entrance. These rocks may have eroded from Gooseberry Neck and their distribution along West Beach may be related to the barrier created by the causeway.

In my memory, East Beach was always full of cobbles, although it was sandy below the upper tides. Beginning at the west end of East Beach there were scattered larger angular rocks on the beach. About halfway down the beach, to the east, there was a large area of exposed bedrock on the land and in the water. Near the east end of the beach, rounded boulders became more abundant on the beach and in the water. During the 1938 hurricane, much of East Beach up to the adjoining road was washed away; this erosion reduced the land area available to build houses after that storm.

About 1929 or 1930, when I was three or four years old, my mother and I walked across the causeway to Gooseberry Neck. At that time, the Neck was covered with grass, with very few bushes. Some ponds could clearly be seen. This was before any houses were built there, but I remember seeing a large barn with a loft. A rope hung down from the loft, apparently used for hoisting animal feed or bedding. There were no animals, such as sheep, on the Neck at that time. Apparently, years before our visits, sheep had been pastured on the Neck and their grazing had kept the bushes in check. The barn was probably built to shelter newly sheared sheep or lambs from the weather. One curiosity I saw were thousands of tiny hop toads which had spent their early lives as tadpole in the ponds. Existing photographs of the Neck taken from Allen’s Point in the very early 1900’s show, in the distance, a building which must have been the barn.

In 1932 during the Depression and near the end of Prohibition, my father was no longer associated with Allen’s Pavilion and did not own our former home on West Beach. In the spring of 1932, my father and mother leased a small building located in Westport on the northwest corner of the intersection of Horseneck Road and East Beach Road, to operate as a restaurant. The newly built structure was called the “Wee Hoose” by the owner, who was Scottish. The building was not insulated or heated and rested on wooden pilings that extended about a foot above the ground. There was no restroom for residents or customers; this need was supplied by an outhouse, which was located about forty feet from the rear of the restaurant. My parents, older brother Stanley Ward Allen, age 12 and I slept in the rear of the restaurant building.

Unlike in the musical Porgy and Bess, summertime living was not easy at the Wee Hoose. Money was very tight, and there were few customers. I was recovering from the mumps, the heavier board used in the Wee House construction was soggy in damp weather, and our mother cat and four kittens succumbed to distemper. The mother cat crawled under the building to die. Because the essence of dead cat was not conducive to fine dining, my father paid my brother twenty-five cents and handed him a shovel to remove the dead cat. Later that summer I was bitten by a chained-up hound dog as I ran through an East Beach resident’s yard. The chain was longer than I expected, so the dog was able to grab me. The doctor treated the dog bite and possible rabies by cauterization – meaning a red-hot iron was applied to the bite site. The bite was on my left leg and a scar remained for many years.

On the upside, we ate well. Meals included tautog, short (sublegal size) lobster, clam chowder, oyster stew, and johnny cakes. Tautog were abundant near shore in those days. My father caught them from Bar Rock, located off West Beach near Allen’s Point. My brother caught them from a small, partially submerged rock located off East Beach near the south end of Horseneck Road. He waded out to the rock towing a surf boat and fished with green crabs or sea clams as bait as the tide was rising. At high tide, with the rock nearly submerged, he paddled his handlines, gear, and fish to shore on the surf boat. We bought fresh vegetables from Ben Cummings, a farmer who lived on the west side of Horseneck Road about three-fourths of a mile north of the Wee Hoose. The Cummings farm was on high land and overlooked Rhode Island Sound, Buzzards Bay, the Westport River, and the Let.

Other memories were of the fox hunts at the Almy (Quonsett) farm, which was in Dartmouth, across Horseneck Road from the Wee Hoose. We would first hear the hunting horn and baying fox hounds, and the see the hounds leap or climb the stone walls surrounding the pastures. They were followed by the horses with red-coated riders, altogether an exciting spectacle. As an aside, there were Catalpa trees in front of the Almy house and my mother and I caught some very large, colorful moths from these trees. My mother later pinned the moths to the restaurant dining room walls to add to the sparce décor.

In the same vicinity, at the end of Horseneck Road on East Beach was the Westport town landing. At the landing there were tide pools and rockweed full of sea critters, so it was one of my favorite playgrounds. This experience and my earlier exposure to sea clams and ocean life on sandy West Beach probably guided me to my later career as a marine biologist.

At the landing, in a cat and mouse game with the lobster warden, lobstermen landed their skiffs on the rocky beach, bringing in legal and illegal size (short) lobsters. The shorts were sold to residents and restaurants when the warden could be evaded. On one occasion, I saw the warden at the landing waiting for a lobsterman to come ashore unload his catch. Unseen by the warden, my father climbed to the roof of the Wee Hoose, diagonally across from the landing, and waved his apron to signal the lobsterman not to land. The warden finally gave up and left the landing. Short lobsters were not on the menu at the Wee Hoose, but lobster meat was. After my father had extracted the meat from short lobsters, he buried the shells in the sand hills off John Reed Road to conceal evidence of short lobster trafficking.

While at the Wee Hoose, I spent my days exploring. To the northwest and west, toward the Let, was a vast jungle of thick maritime bushes through which I walked and crawled. To the east is Dartmouth, and I would climb all over the impressive Quansett Rocks.

That summer, my brother Stanley had a young friend whose parents had a cottage on East Beach and kept a small sailboat. At age 12, Stanley and his friend sailed out to Hen and Chickens Lightship anchored at the entrance to Buzzards Bay and sold used magazines to the ships crew. My brother had a magazine route on Horseneck Beach. It was Liberty magazine, a popular weekly that sold for five cents a copy, however, he had few customers and retired from the route before the end of the summer. Then, beginning in September, my mother drove my brother and me to and from school in Fairhaven, five days a week.

As summer changed into fall, the temperature in the Wee House began to drop. The underside of the building was open to the elements, so we stacked salt marsh hay around the perimeter in an attempt to conserve heat. As a child of that era and of that family, it was expected that I would participate in any work that I was capable of doing, so I helped stack the marsh hay around the building. In the fall, to make oyster stew for the restaurant, my father, brother, and I collected oysters in the Westport River near Hix Bridge where they were plentiful. My father also bought oysters from Lester Bowman, a Westport fisherman. We lived in the non-winterized Wee Hoose until November 1932. With few customers and only oyster stew on the dinner menu, we were finally driven out by the cold weather to live in Fairhaven with my mother’s relatives temporarily, as we had no other home at the time. We never returned to the Wee Hoose, which along with other East Beach buildings, did not survive the 1938 Hurricane a few years later.

During our time at the Wee House and in earlier years at Horseneck, our family became friends with many other Horseneck residents, some of whom drowned during the Hurricane. These unfortunate people included Frederick Burden Head; the Sags of Horseneck Beach and long-time residents on East Beach from the 1800’s; some members of the Tuell family from Providence; and Charles and Alpha Soule, who had a small variety store and restaurant on the north side of East Beach Road, near the Let. The Soules had a small back room in the restaurant where only certain members of the large Horseneck Beach community were admitted. This selection of customers was because there was a one-armed bandit (an illegal slot machine) in a recess in the room’s wall. When not in use, the bandit was hidden from view by an overhanging cloth.

In 1932, Charlie Soule was also a lobsterman, who used his oar powered skiff to set his pots (traps) off the middle of East Beach. While transporting pots, Charley stowed the attached, coiled pot line and buoy inside the pot to avoid entanglement. When ready to set a pot, the buoy and line was removed from the pot. One day, Charlie took my brother, Stanley with him to set pots. Stan, in an attempt to be useful, threw a pot into the water that still had the buoy inside. The lost pot was an economic blow, but Charlie was a good-natured man and remarkably tolerant of the actions of my brother and me.

Charlie Soule also raised homing pigeons as a hobby. Some of his pigeons did not meet his standards as “homers”. He gave two reject pigeons to my brother and me, together with instructions on how to build a pigeon coop. Charlie was an ingenious man. Homing pigeons need to be restricted to their coop after returning home. To secure the pigeons in our coop after entering, Charlie gave us a one-way wire door from an old lobster trap. (In that era, one-way doors were used in lobster pots to prevent lobster escapement after they entered the trap.) We built what we thought was an adequate coop behind the Wee Hoose. Our pigeons only homed once, from a release near Hix Bridge in Westport. When released in Fairhaven, our pigeons joined a large flock of homing pigeons, preferring to stay in Fairhaven and never returned to their fine coop at Horseneck Beach.

Although we lived in Fairhaven after the Wee House experience in 1932, we still spent time at Horseneck Beach because my grandmother, aunt, and uncle lived there in the summer while the Pavilion was in operation. In 1936, my brother, then 16 years old, lived with our aunt and uncle at Horseneck. He worked at the Pavilion grocery store and delivered groceries and ice to Horseneck residents.

During the 1938 Hurricane, my immediately family and I were living in Fairhaven, but my grandmother Allen and my uncle and his wife Marion Reed Allen, were at Horseneck Beach, near Allen’s Point. Even after several terrifying experiences, all three relatives survived the storm. My grandmother’s house was surrounded by Allen’s Pavilion (built of concrete) and was situated up high, about ten feet above street level and above the bath houses. This positioning gave her house some protection from the rising water and she witnessed all the fury and devastation taking place. During the storm, she stayed in the house which had a solid foundation and remained in one piece. Much of the Pavilion and my uncles house, about six or seven lots north of the Pavilion, were destroyed. My uncle, his wife, and other West Beach residents escaped the rising water by climbing onto the highest sand dunes of West Beach. The hurricane surge moved the Alton Ward Allen house (no longer owned by my family) off its foundation and across West Beach Road, as it did other houses along West Beach. A photograph in the New Bedford Standard Times on October 1, 1938, showed our former home, essentially in one piece, at its post-hurricane location.

https://buzzardsbay.org/download/hurricane-38-nbst.pdf

Buildings on Horseneck after 1938 hurricane

A few days after the storm my mother and I (I was 12 years old) entered the kitchen and found it in fairly good condition. I think one or two porches had been torn off the building. Sometime later, the house was moved back to its original foundation, where it stands today.

My aunt and uncle managed Allen’s Pavilion from about 1930 to about 1964. The Pavilion was open in the warmer months of the year. During that time, my aunt Marion gave piano lessons in Westport. After the hurricane, my uncle rebuilt the badly damaged Pavilion and he and my aunt lived in a small apartment built above the restaurant each summer until early fall. The Pavilion was damaged again by hurricanes in 1944 and 1954 and my uncle rebuilt each time.

In the 1950’s my father, A.W. Allen, was Assistant Director of Parks (Massachusetts). Due to his knowledge of the Horseneck Beach environment and his past experiences in trucking roadbuilding material, construction on sand, and restaurant management, he was instrumental in planning and development of the so-called “State Beach” complex, located along Horseneck’s West Beach.

My time at Horseneck Beach did not end with the 1938 Hurricane. My brother and I often visited my grandmother, and aunt and uncle at Allen’s Point. These visits were interrupted by World War II, when we both served in the U.S. Navy, and later by our careers, which were located distant from Horseneck Beach. My grandmother lived in her Allen’s Point home each summer and early fall until she died in 1955. After her death, my uncle rented the house to tenants. The Pavilion and the house were sold about 1964 and my aunt and uncle left to live in Fogland, Rhode Island, near the Sakonnet River. The former Allen’s Pavilion became Chandy’s by The Sea Clam Shack. Years later, after the Chandelais family sold the Clam Shack and house, these buildings were reconstructed and remodeled into a modern beach home with a nearby apartment. (Current address is 151 West Shore Road).

Beginning in the 1950’s, our family and friends spent many enjoyable summers in cottages on the East Branch of the Westport River. As of 2022, some of my extended family still follow that tradition along the Westport River.