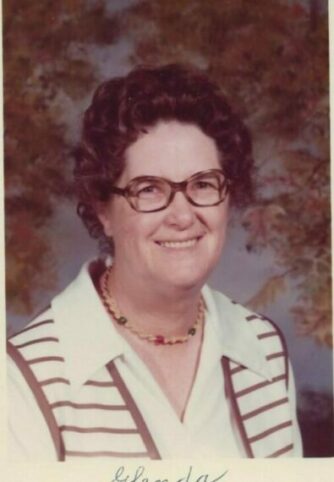

Glenda Kirby Taber Broadbent (1918-2014)

Posted on March 1, 2024 by Jenny ONeill

WOMEN OF WESTPORT POINT

GLENDA BROADBENT

Teacher and historian

1779 Main Road, Westport Point

“Those of us who grew up in Westport Point are the most fortunate people in the world. We had the river, the ocean, the world. We cared for everyone and everyone cared for us.” Glenda Broadbent

Glenda was born on The Red Farm at 1838 Drift Road and passed her childhood at a family home on 1950 Drift Road which her father, Andrew Taber, built. She and her husband Walter Broadbent, built their home at 1779 Main Road on property passed to her by Katherine Stanley Hall. She lived her entire life in Westport.

She became interested in learning at a very young age and loved books. She even skipped first grade and started school in second grade.

Glenda Broadbent as a young girl

Glenda attended Hyannis Teachers College on Cape Cod. After graduation she taught school at Brownell’s Corner from 1939-1942, Westport Point from1942-43, Dartmouth Cushman and Bliss Corner from 1943-1944, Russell’s Mills from 1944-48, Gidley from1952-53, Earle School from 1967-68, Westport Point School from1968-70, Macomber from 1970-81. She retired in 1981.

In 1963-67 she was the librarian for the town of Westport.

After she retired, she started writing stories of Westport Point and her experiences growing up. She was the historian of the Westport Point Methodist Church and wrote a book about the history of the church, which is now in the Smithsonian Museum. She was a member of Norma Judson’s History Study Group in the early 2000s. She wrote and did research for the Westport Historical Society.

She wrote stories about diverse topics in Westport, but often about life at the Point. Her stories are full of her own experiences such as riding on the cart when Franklin Roosevelt was taken to Louis Howe’s cottage on Horseneck West Beach and meeting the soldiers stationed on Gooseberry during WWII. Several interviews with her and Walter and her sister and brother in law, Shirley and Ab Palmer, are available on the Historical Society website.

Glenda was given a lifetime achievement award by the Westport Historical Society in 2012.

By Betty Slade, with thanks to Glenda’s family.

A Walk to the Village by Glenda Broadbent

The village of Westport Point got its start on Horseneck Beach. Families from Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies built their homes amid the dunes and put in wharves along the river. As the Indian menace was overcome, others came from the Newport and Providence areas to establish farms.

Tradition tells us that our older Cape-style homes were moved here from the Horseneck dunes. Families with homes clustered around the wharf cleared land for farms and orchards farther up the hill.

Around 1830, the village had expanded as far north as the Palmer house. For the next hundred years that unofficially became the northernmost boundary of the Point. In the 1940’s, a sign just south of Southard’s lane still informed you that you were now entering Westport Point.

Those of us fortunate enough to be natives still feel the need to check out the village each day. Going to the post office gives us an excuse for extending our ride to the wharf to turn around. How else are we going to find out going on in the rest of the world?

We continue to regret the loss of our country sidewalks below the church corner. How pleasant it was to follow a patchwork of paths over gravel sidewalks or grassy lawns. Some parts were muddy on rainy days, or were like glue where wood ashes were dumped. Some paths skirted beach plum bushes and wild flowers. Chi always walked on the cemetery wall. They tried to walk across the gates, too, then ran across the yard to get to the next stone wall. (Will Brightman didn’t approve, but we had to get to that next stone wall, and he certainly didn’t like us making toe holes in his bank to get to that wall either.)

In several places along the paths, trees had been planted between the road and the sidewalk. Only the remnants of the elms remain. How our grandparents worried when the road was paved. They were sure the steam roller would damage the roots that grew into the street and the trees would fall on the houses. Some trees still show where their roots were chopped back on the street side.

There was another smaller type of tree about the size of a maple planted along the sidewalk in front of #1933 and then on the east side below the post office. Does anyone remember what kind it was?

Nearly every yard had a spruce tree that had grown to at least 60 feet tall most, like the one just north of the library cottage, had been shaped by the prevailing winds. Few remained after the 1938 hurricane.

Horse chestnut trees were popular. Girls hollowed out the nuts for doll’s dishes. Boys used them in lethal ways. Sling shots needed ammunition. Nuts tied to the end of a string, twisted swiftly and released, were deadly weapons. Many were attached to twigs and became make-believe pipes.

We check fences, too. Some are still where we expect them to be – built there more than a hundred years ago. Others are so new we have not accepted them yet, even though some years have passed since they were built.

Possibly the oldest wooden fences were the solid wooden ones. Their wide boards may have been brought to the lumber yard at the wharf by boats from the Point that went to Maine for lumber. Many of these still separate yards from the sidewalk to the river below Valentine Lane. Up the street, one separated #1942 from the big yellow house next door. Another was along the sidewalk in front of #1948. It was painted white and woe be unto anyone who scratched or marked it. (Boys often carried sticks which they dragged along a fence making a sort of music as the stick hit the iron or wooden pickets.)

Of course, the most eternal are our former-built stone walls. They assure us with security and steadfastness. There are several variations in the village. At #1903, the slanted top and gateposts are unique.

While we expect picket fences in New England, those here on the Point are mostly the capped variety. Those, too, have withstood the storms and changes of the years. There was one at #1900 long ago that was quite different. It had a saw-toothed capped top. Probably it had been painted barn red, then repainted later with white, for it had weathered to a rosy gray.

The capped top fences were a big help when we were learning to ride a bike. Prop up the bike next to the fence, get on, and push yourself along by hanging on to the fence cap. Get up speed and shove off. The first bike we shared was built by the Cornell boys, It had a bicycle frame, a 28″ bicycle wheel on back, a 6″ wooden cartwheel on front, no pedals, and no seat. Amazingly, we got a short ride after we pushed away from the fence.

Several places used iron fencing. Many had become rusted and broken. During World War II, these were taken down and supposedly made into bullets. It is heart-warming to see the fence at the Palmer house replaced with one so nearly like the old.

While we note the changes – yards that had fences and now are open or those that were open and now are guarded by a stone wall or picket fence – we appreciate how well our village and its homes are being maintained.

We can still be proud to say we live at Westport Point.

The Westport Point Library and Our Miss Hall

By Glenda Broadbent

Those of us who grew up in Westport Point are the most fortunate people in the world. We had the river, the ocean, the world. We cared for everyone and everyone cared for us. True, we suffered the summer people in July and August, but we could look forward to Labor Day when THEY went home. After that WE owned the Point, and WE had Miss Hall.

Miss Katharine Stanley Hall was the librarian at the Point Library. She listened to us, she knew our hopes and fears, and she encouraged us to make our dreams come true. She also made sure that we read books that would help us achieve those goals.

The first library at the Point was probably established by William Watkins, an Oxford educated man who came here about the time of the Revolutionary War.

In “The Village of Westport Point”, there is mention of a case in the library with 85 books that originally formed part of a school library established in the village about 1840 by Dr. George White, school teacher. That case and books were donated to the Westport Point Library in 1904 by Drusilla Cory and later the case was given to the Methodist Church by Mr. and Mrs. Robert Church.

But the library I remember from my childhood was in two south rooms in the cottage at 1871 Main Road. We used the front door which led into a hallway and then into sunny rooms where bookcases were all around the walls. In the second room a heavy piece of furniture with drawers on the bottom and glass doors at the top held many fascinating objects which the Hall family had brought from the Orient: bird’s nests with 3 or 4 apartments, an ostrich egg, a red, white, and black rolypoly god one worshipped by throwing spit balls at it, and so much more. Sometimes Miss Hall would let us handle one of these treasures while she told us its story.

In the summer we often waited in the seats outside the front door for Miss Hall to come from her home way down Scotch Pine Lane. How we resented the fact that her large summer family took a good deal of her time!

As the days got colder the chill in the library rooms did not really bother us. Miss Hall would start the portable kerosene heater. This was of black metal about 30” high and 10″ diameter. The top had round holes about the size of a nickel around the outer edge. Miss Hall often brought a bag of marshmallows to toast over its fire. This was done by putting a marshmallow over each hole, and when the bottom melted down into the hole, it was turned over to toast the other side.

It must have been in the late twenties when the building in the back corner of the lot was built especially for a library. Will Brightman and Carl Wing did the work. On one very cold windy day the books were moved from the cottage to their new home. Kids came from far and near with wagons and even a wheel barrow or two. As we went through the yard the wind whipped open the books, sending loose pages flying into the air–later to be found as far away as Drift Road and Masquesatch.

As one entered the new library, on the right was the children’s section. The original outdoor sign had been made into a little table on which were picture books and stereoscopes. How fascinating it was to view the double pictures through the scopes, which made them seem three dimensional.

One bookcase held books in memory of the child Mary Boyd Wicks. A music box was kept wound so children could watch the metal teeth strike the little points on the roller and listen to its tinkling song.

Double bookcases were built between each window, and under each window were seats where one could curl up and read all afternoon. Strings and strings of beads were hung at the entrance to each alcove and at each window. Paintings and burnt wooden signs made by Alden Wicks were hung along the center aisle. On the back wall was the display case, a case of John Babcock’s doll furniture, and more books.

Beyond the children’s corner was the alcove with girls books, the Bobbsey Twins, the Ruth Fielding series, Pollyanna and the Louisa May Alcott books. The stacks for boys held Tom Sawyer, Tom Swift, The Rover Boys, and the Horatio Alger stories. Both areas contained stories of other countries, adventure, and mythology.

Across the aisle three double stacks held adult fiction. When teenagers asked for romantic novels they were advised to read The Secret Carden and Anne of Green Gables before graduating to books by Emilie Loring and Grace Livingstone Hill.

All books were carefully selected. Miss Hall’s mother read each one, and blacked out words and removed pages that were offensive. Others wrote positive or negative comments in the margins.

Books were “borrowed.” They were never “loaned.” Loaning meant you were duty bound by records. Borrowing implied you were trusted to care for and return. There were no library cards or due dates. The limit was the number you could carry. So on Saturday afternoon and Tuesday and Wednesday mornings when the library was open to school children we went with our wagons to be sure we could take home enough books to read until the library was open again the next week.

The library also gave us an opportunity to meet people who had travelled beyond Fall River and New Bedford, even beyond New York and New Jersey. In our eighth grade English class we read of Sir Wilfred Grenfell’s experiences as the first doctor in Labrador. On the way home from an isolated village he became marooned on an ice floe and had to kill some of his dogs in order to survive. One of the nurses at his mission was our Miss Luther, who lived on Cape Bial Lane. We listened in awe to Miss Luther’s stories and were thrilled to meet Dr. Grenfell when he came here to raise money for his mission.

The library was supported wholly by the Hall family until 1929 when the Town of Westport gave Miss Hall $200 toward the cost of heat and lights. That dwindled during the depression years to $100 a year and did not ever return to the original amount. In 1948 Miss Hall was no longer able to maintain the library. The 3,500 books were given to the Westport Library, then at Central Village and the town paid $58.75 in moving costs.

Those of us who grew up here remember Miss Hall with love for the world she gave us.