Clarkson Macomber Journal

Clarkson Macomber journal

Read the transcribed journal here.

Read excerpts from the Clarkson Macomber journal here.

Read about the John Macomber farm and family by Richard Gifford here.

Read Marianna Macomber’s recollections of Central Village here.

Read Lydia Macomber’s letters here.

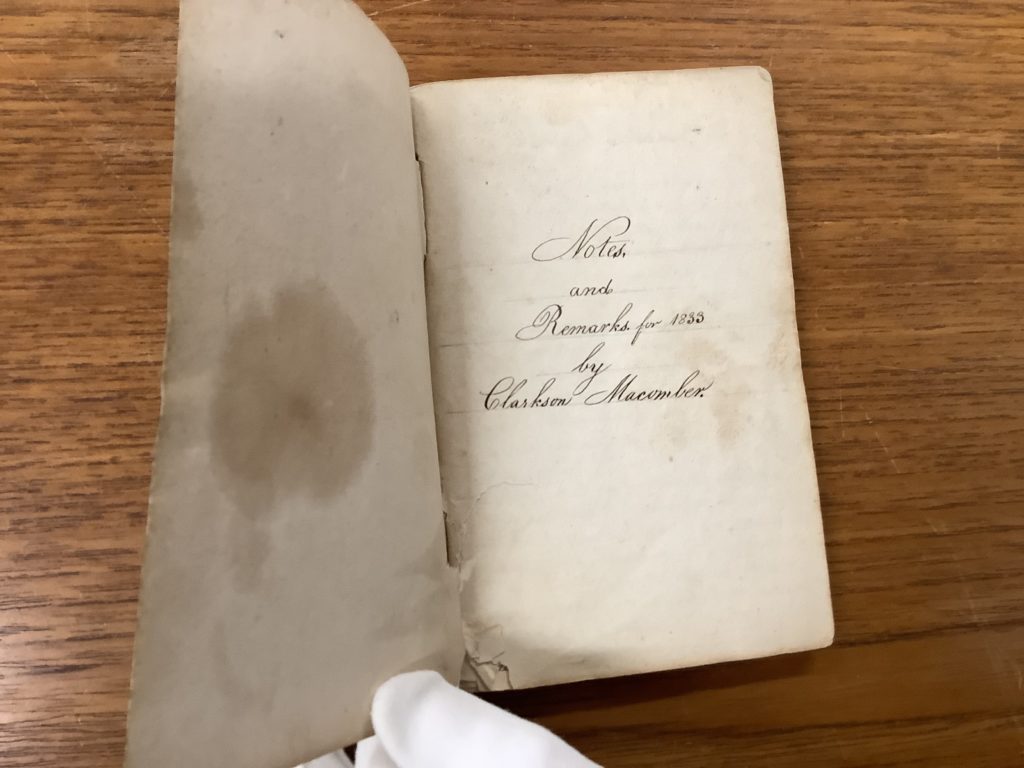

Notes and Remarks for 1833 by Clarkson Macomber

By Jenny O’Neill with thanks to Richard Gifford and Robin Winters

The journal of Clarkson Macomber (1813-1835) provides many fascinating details about everyday life in early 19th-century Westport. His recently transcribed “dayly journal” for 1833 is part of the Westport Free Public Library’s history collection. I am most grateful to Robin Winters at the Westport Free Public Library for her help locating and transcribing the journal and to local historian Richard Gifford for sharing additional Macomber family history.

Amidst a community primarily focused on agricultural and maritime activities, Clarkson Macomber presents an unusually intellectual persona. At the age of 20, he was a studious and serious young man. He was preoccupied by his own poor health, with an interest in the temperance movement, and in questions of religion, preferring to spend his time studying rather than helping on the family farm.

Tragically his life was cut short by one of the most dreaded illnesses of the time, tuberculosis (also known as consumption). Classic symptoms of tuberculosis of the lungs included fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and chronic coughing and the spitting of sputum containing blood. Weight loss and the so-called ‘wasting away’ associated with TB led to the popular 19th-century name of consumption, as the disease was seen to be consuming the individual.

Man suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. Illustration from Kranken-Physiognomik / by von K. H. Baumgärtner / 1929. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Throughout his journal, Clarkson often noted the poor state of his health. He described feeling “weak and feeble” or “dull spirited” and he suffered from headaches and poor appetite: “troubled with the sourness of my stomach.” He made careful note of his body weight. At the beginning of the year, he weighed 128 pounds, dropping to 101 pounds by the end of the year. He sought to alleviate his symptoms with anti-bilious pills purchased at the Head of Westport and by chewing Indian Hemp root. He ingested “some water infused with vegetable bitters.”

Clarkson succumbed to this disease in 1835 at the age of 21. Sadly, his brother Alvah also contracted tuberculosis and died a few years later.

More broadly (and indirectly), the journal offers insights into the obscure history of raising silkworms here in Westport, the Macomber family’s role as originators of the Rhode Island Red breed, their care for deaf family members, and the educational aspirations of a farming family. Some of these stories will be shared in the coming months.

A Quaker family

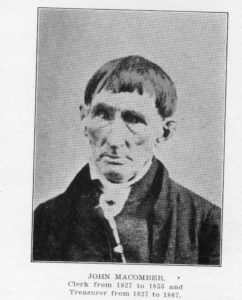

Clarkson’s family was closely associated with the Westport Monthly Meeting of Friends. His father, John Macomber, was its Clerk for many years. According to his great granddaughter Marianna Macomber, John Macomber was regarded as “a man ahead of his time” who “followed the early Friends idea of simplicity of dress and lack of color. A granddaughter of his, whose mother, although a Friend, had a love of color and clothes, went up to him and said, “Grandfather, see my red stockings and new bronze shoes.” To which he replied, “I see all I want to of them.””

John Macomber, father of Clarkson Macomber.

WHS 2005.122.161

The unusual name of Clarkson may have originated from the Macomber family’s support of the abolitionist movement. According to local historian Richard Gifford, he may have been named for Thomas or John Clarkson, prominent British abolitionists.

Clarkson embraced the life of a Quaker:

“they gave me an invitation to go to Tillinghast Sowle’s but I preferred to stay to home and to read and write of the Scripture Questions from The Friend.”

His journal includes a surprising encounter with President Andrew Jackson in Newport R.I. while attending the Yearly Meeting:

“The streets began to be considerably thronged before meeting with people who were in anxious expectation of the President of the U.S.A. … some young friends staid out of the meeting and others went out to see the procession but I rejoice I stayed till meeting was through … After supper I went up to the President quarters I was introduced to him by Gov. Collins…I saw Van Buren but did not choose to speak with him.”

The Macomber Farm on Main Road

Clarkson grew up on a large farm owned by his father John Macomber located in the vicinity of Central Village. The Macombers dominated this stretch of Main Road. John Macomber was known for his tree nursery and for his mulberry trees, grown specifically to provide nourishment for silkworms, supporting a small-scale silk making industry. There is mention of a warehouse for the silkworms and he noted when the silkworms began to spin. “Mother went to watch with H. Lawton”

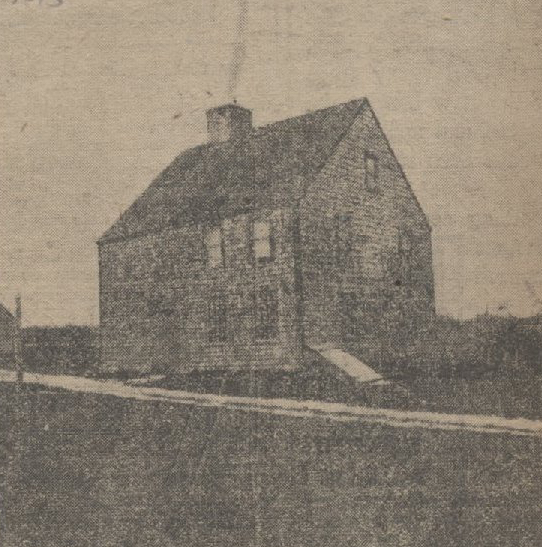

Clarkson grew up in this house that once stood on the west side of Main Road.

WHS 2005.101.015

Although farming was not a significant activity for Clarkson, he did on occasion help his father with farming chores. He planted mulberry trees, sugar maples, apple trees and cherry trees. Other crops included oats, parsnips, watermelons, radishes, potatoes, cabbage, turnips, huckleberries and blackberries.

School master

At the time of writing the journal, Clarkson was a teacher at the school on Horseneck Road, located just south of Cross Road. He boarded nearby at the home of Henry Wilcox, a wealthy farmer. The house still stands today at 775 Horseneck Road.

Clarkson boarded at the home of Henry Wilcox located at 775 Horseneck Road.

An undercurrent of dissatisfaction with his students runs throughout the journal:

“I had to warn the schollars against persisting in snow balling.”

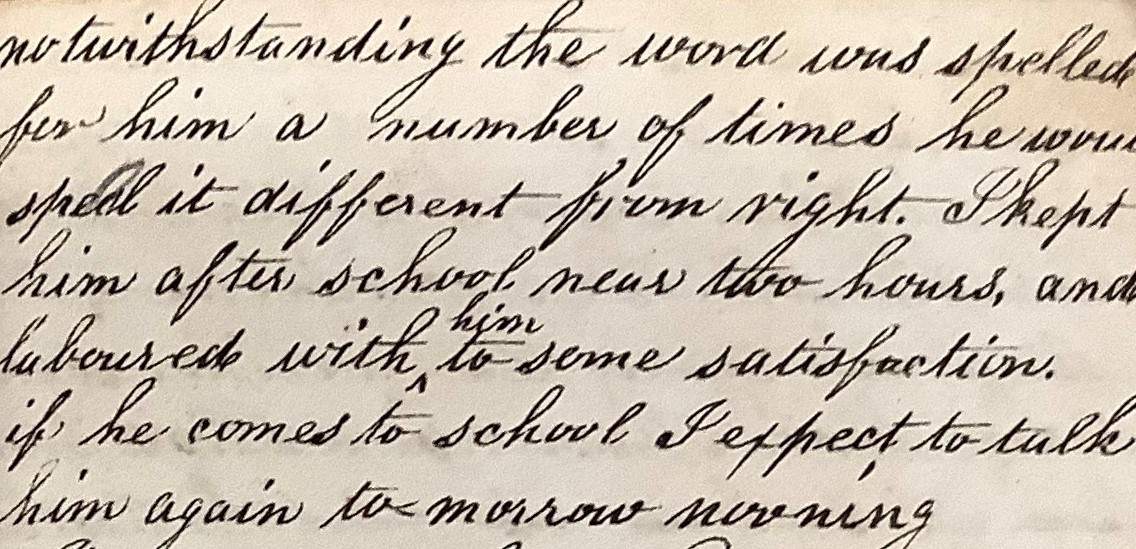

“Willium Durfy brought his writing book again today with more than a page wrote over as it suited him: when he was spelling out of the book to night he would not spell the word s -t-a-i-d notwithstanding the word was spelled for him a number of times he would spell it different from right. I kept him after school near two hours, and laboured with him to some satisfaction. if he comes to school I expect to talk him again tomorrow morning.”

Clarkson’s use of corporal punishment was not unusual for this era. He recounts a few confrontations with his “schollars.”

“Lorenz Underwood forgot how to count today but he recalled after I sent for a stick.”

“It appears that Jason Gifford fished an India rubber ball(?) from the pocket of Richard Gifford. I kept him standing upon the bench and the floor most of the afternoon. Wm. Durfy was so stubborn and contrary, I sent for a stick. A nice one was brought. I then ordered him … to take off his jacket but he refused. I then tried to pull it, finding it impractable. I took some red twine to ty his hands but he said no, his hand should not be tied. I then called upon Elijah for assistance and after considerable struggle fastened his hands and by means of a line fastened them to a spike where I kept him till said was ready to pull off his jacket. His hands were untied, he pulled it off then he received his chastisement after which he said was sorry. He was then required to confess that he was sorry to the school.”

Temperance

“Hannah come to into the school room to night and talked some about the Friends drinking rum… she says that they drink more than others except two or three drunkards.”

Temperance, a popular reform movement of the era, is a dominant theme throughout the journal. Clarkson regularly attended Westport Temperance Society meetings at the Head of Westport. He discussed the topic with his friends on many occasions and attempted to educate them about the dangers of alcohol:

“I gave away 3 Temperance tracts to night. My schollars are too much engaged in catching frost fish I fear.”

His interest in the temperance movement was not universally shared: “This is the day for simultaneous meetings of the Friends of Temperance throughout the United States. I made an attempt to form one in my school but an unsuccessful one.”

At the town meeting Clarkson observed: “It was voted that no ardent Spirits be sold or handed out the town house but wine and cider were plenty.”

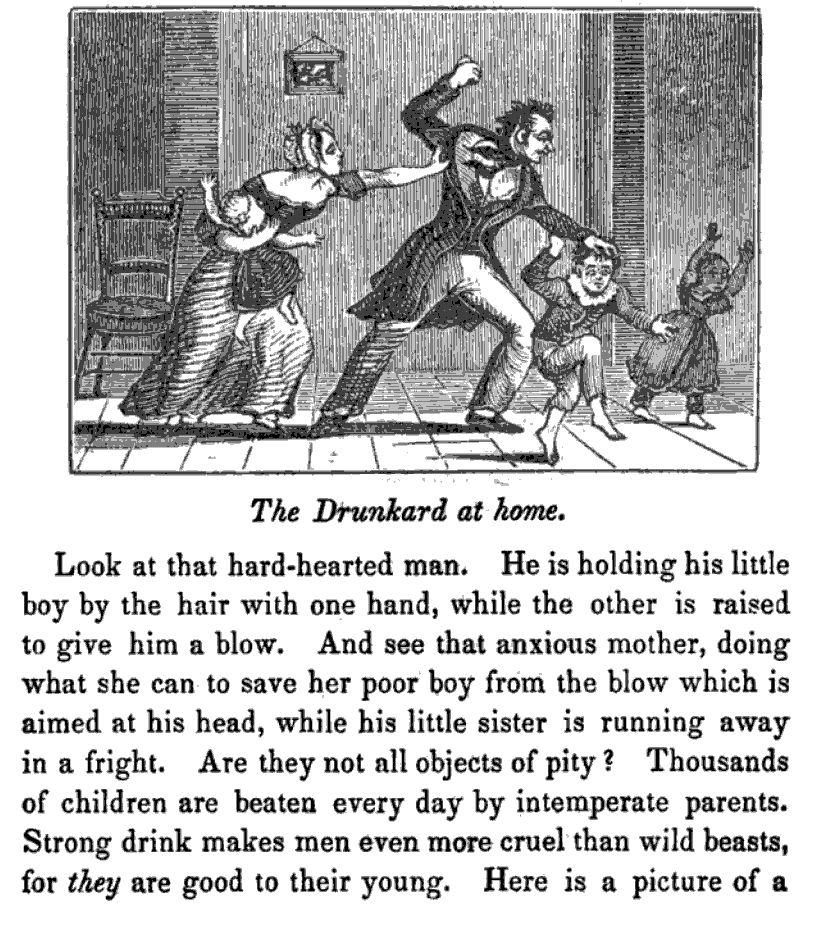

Clarkson enjoyed reading The Youth’s Temperance Lecturer written by Bostonian Charles Jewett (1807-1879). Jewett aimed to educate young people about the dangers of alcohol, relating the tragic story of a father who, in a drunken rage, killed his baby boy and reminding his readers that they can be held accountable for their actions, even if those actions were a result of drunkenness.

The Drunkard at Home, illustration from The Youth’s Temperance Lecturer.

Clarkson recorded varied reactions to his interest in temperance:

“Ephraim and Susan Gifford were here this evening. The Lecturer was read which was laughed at by some and praised by others.”

Further context for the local effort to curtail consumption of alcohol https://wpthistory.org/2010/06/the_washingtoni/

Interests

“I trimmed trees with father this afternoon and obtained his consent to have two hours in a day for study provided I am industrious the rest of the time.”

Clarkson was a natural scholar with a fondness for discussions of an intellectual nature. Among the books, tracts or interests mentioned in his journal are the following:

- The “Himmalah (sic) mountains”

- “Man as an Object of Natural History”

- Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia

- The tract on Roads and their Construction

- A tract about bees “which I found to be quite interesting.”

- The tract on Ornithology

- “I have just been reading of a balloon ascent.”

- “I have been interested in reading Thompsons description of haymaking and sheep shearing.”

- “Received The Histories of the U.S. subscribed for by GWF and me”

- “I brought home from N. Bedford a map of Pallestine”

Clarkson enjoyed ardent intellectual debates with his friends:

“we discoursed about the velocity of falling bodies. He argued that a body would increase in velocity for a certain distance and then it would move on with uniformity.”

“Elijah and I were ingaged in an argument respecting the rotation of the sun round the earth. He maintained that the sun went round the earth and appealed to the Book of Joshua to prove it.”

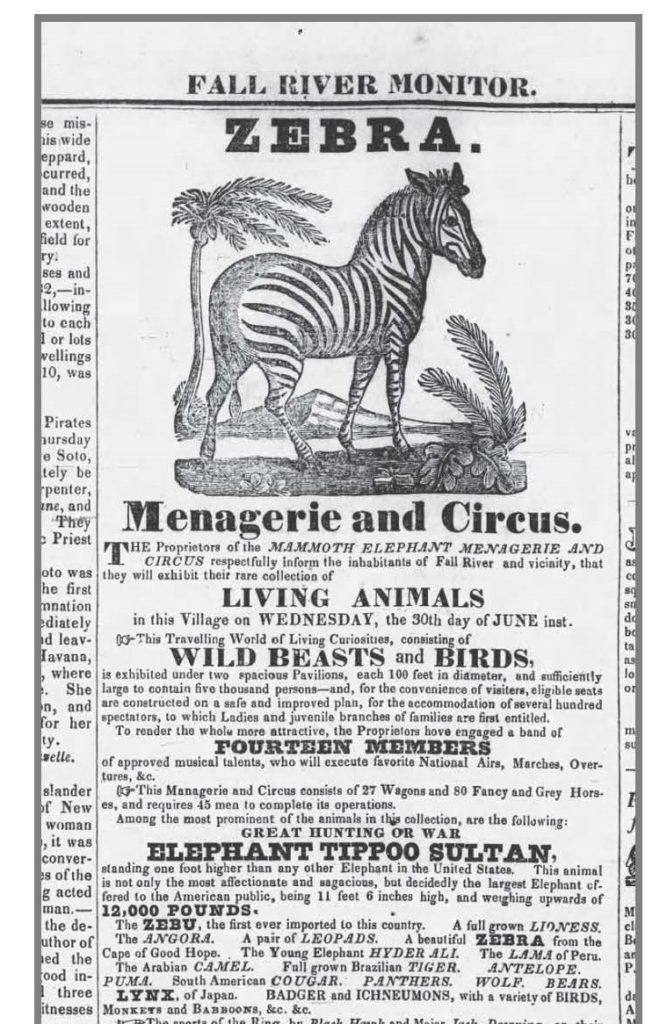

Preferring scholarly and religious activities, Clarkson rarely indulged in entertainment. He attended the National Menagerie at the Head of Westport, a travelling zoo of exotic animals such as elephants, camels, leopards, monkeys, tigers, llamas, and baboons.

“I gave 25 cents to the National Menagerie, a large collection of wild animals but I rather disapprove of giving so much money to unprincipled men. I think the money and time be better spent in purchasing and reading some Natural History of the animals exhibited.”

Advertisement for a traveling menagerie, Fall River Monitor Sat June 13, 1835.

Towards the end of his journal, Clarkson describes his journey to Providence R.I. to attend “the school” (possibly the Moses Brown School) where he studied mineralogy and algebra. His sense of achievement is conveyed in a short note: “I feel pretty smart.”

Clarkson Macomber is buried with other family members in the cemetery behind the Central Village Quaker Meeting House. Photo: J. Bosworth. http://westportmacemetery.org/home.cfm

Genealogy

Father: John Macomber (1785-1867)

Mother: Mary (Slade) Macomber (1784-1861)

Siblings:

Lydia Macomber Webster 1811–1892 (born deaf)

Alvah Macomber 1816–1839

Leonard Macomber 1818–1873

Elizabeth Macomber 1823–1841

Hannah Macomber Davis 1824–1851

Olive Macomber 1827–1900 (born deaf)

Mary S. Macomber 1829–1910

Read the transcribed journal here.

Read excerpts from the Clarkson Macomber journal here.

Read about the John Macomber farm and family by Richard Gifford here.

Read Marianna Macomber’s recollections of Central Village here.

Read Lydia Macomber’s letters here.