Over view of Native American presence in Westport

Posted on June 28, 2014 by Jenny ONeill

Westport’s recorded histories contain numerous references to Native American settlement and activity areas and the existing archaeological record for the town supports this presence. Native people who utilized Westport’s abundant natural resources most likely remained in the area well into the historic period, especially given the slow and highly dispersed colonial settlement within the present-day town.

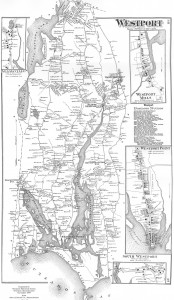

One historic period Native American site was recorded in Westport prior to the survey (WSP-HA-1), and this site constitutes the only historic period archaeological site in the MHC’s files (Herbster and Cox 2002). Several burial grounds recorded in town records suggest that additional Native American sites dating to the historic period are located within the town. At least three cemeteries within Westport are known locally as Indian burial grounds. One of these cemeteries, designated as an “Old Indian Burial Ground” appears on the 1871 map of Westport near the intersection of Cross and Howland roads. Historian Eleanor Tripp described two additional Native American cemeteries in Westport. Both sites are located on the East Branch, and one of the two is reported to have “tomb stones on which are cut Indian pictures,” a possible reference to pictographs or other symbols (Tripp n.d.:16).

Although there is no specific information available about the individuals interred in any of these possible burial grounds, most contain unmarked fieldstones set within a designated area, often in somewhat ordered rows, including possible head and footstones . This type of cemetery is typical of Christianized Native burial grounds documented elsewhere in the region.

Numerous Contact (A.D. 1500–1620) and early historic period Native sites have been recorded in Dartmouth, where settlement appears to have been focused around the Apponagansett Bay area (Herbster and Cox 2002). Sites from this period in Dartmouth have been identified primarily through the accidental exposure of unmarked burials containing both Native-made and European objects (e.g., shell [wampum] beads and English clay pipes). Many of these features have been identified along the coast or near the coastal margin. Similar unmarked burials could be located anywhere within Westport, although they could be more concentrated near the coastline and along the margins of the Westport River. Burials could be present as isolated features, within clusters, or associated with a larger habitation/activity area.

The ethnohistoric record for the region indicates a strong Native presence in the Old Dartmouth area in the seventeenth century and the maintenance of many Algonquin place names in Westport suggests that these designations were transferred through Native and non-Native interaction in the historic period. Sites types from the early historic period would likely be similar to those expected in the Woodland Period, and may be difficult to differentiate without clear temporal indicators. Sites could include large, semipermanent habitation areas represented by features including traditional structural remains (wetus/wigwams), shell midden deposits, chipped-stone and/or metal tools, and planting fields.

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century Native American settlement and land use patterns in Westport are not well known, but it is likely that homesteads were established in outlying sections of town that were not immediately claimed by white settlers. The presence of unmarked gravestones and small, partially undefined burial grounds attributed to Native Americans suggest that family and/or extended kin groups may have been living in proximity to these areas. Eighteenth-century Native American archaeological sites could be expected to include some of the components listed above, with an increased likelihood of Euro-American objects and structural remains (e.g., fieldstone foundations and/or cellar holes).

Reflecting a pattern seen elsewhere in coastal Massachusetts, it is likely that many Native American men became involved in the maritime industries in Westport and the New Bedford area during the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. Ships’ logs and other records may contain additional data about Native residents who followed this trade.

The presence of Native people in nineteenth-century Westport is documented in the 1861 Earle Report, commissioned to collect census data about indigenous Massachusetts residents. “Dartmouth Indians” are listed as those persons belonging to the Wampanoag Tribe who were in earlier times known as the “Acushnets, Acoaxets, and Aponegansets, by which names the several localities of their residence are still known (Earle 1861:111). Earle noted that because of a lack of common lands or state-enforced reservation, the Dartmouth Indians had generally been incorporated into the community rather than segregated into one physical section of town. Earle’s report specifically notes, however, “the most numerous settlement of them being on the west side of Westport River” (1861:111). The reference suggests a concentrated Native community along the West Branch, although more specific data is lacking. A community in this area is also suggested by the “Old Indian Burying Ground” depicted on Old Harbor Road on the 1871 map of Westport.

The report also describes an 1859 petition to the Massachusetts legislature filed by Native American residents of the Dartmouth area. The petition claimed that large tracts of land in Westport and Dartmouth were owned by non-Native people who did not have clear title, and requested the return of these lands to Native descendants (Earle 1861). Included in the document were accounts collected from Native people who were in their 80s and 90s at the time, who told of old wigwam settlements, cornfields, and at least two burial grounds along the Slocums River in Dartmouth (Glennon 2001:52). After review, the Senate rejected the Indians’ request.

The 1861 Earle census recorded 111 Dartmouth Indians within 29 families. Of this total, 99 persons were listed as “Natives” while 12 were listed as “Foreigners and unknown.” Nearly half of the total population was between the ages of 21 and 50; 17 were less than 10 years old, and six were older than 70 years of age (Earle 1861:111). The census includes information about age, sex, marital status, occupation, land in severalty and “Tribe or Race.” Some of the individuals are designated as “Colored, (for.)”, a reference to persons of African or non-European descent.

Nearly half (50) of the 111 Dartmouth Indians recorded during the census are listed as Westport residents. These individuals include members of the Crouch, Marston, Nicholson, and Phelps families. Nineteen individuals with the surname Wainer are grouped into six separate family units, all residing within Westport (Earle 1861:Appendix, lxv–lxxi). Six Cuffe descendants are also listed, and the report makes specific note of their ancestor Paul Cuffe as a “native of this tribe, of mixed Indian, African and white descent” (Earle 1861:112). Charlotte White is the last name on the Dartmouth roll, recorded as an 84-year old “Indian Doctor” with 11 acres of land. Although her town of residence is not listed, Charlotte White Road in central Westport is an apparent reference to this woman, and may suggest the general location of her former homestead. Local historical sources indicate that White is buried on property on this roadway (B. Wyatt, personal communication 2004).

Most of the Westport Native American families appear to have been landholders. Alice and Benjamin Cook owned 12 and 15 acres respectively. Samuel Cuffe, head of the recorded family, owned 40 acres. John Marston owned “35 acres land, with buildings,” and various members of the Wainer family held 30, 32 and 50 acres each. A review of the 1871 Beers map identifies several Wainers along the southern end of Drift Road, along with a small cemetery that could possibly be associated with this kin group. One town history refers to an Indian burial ground located somewhere on Drift Road, and this reference suggests the possibility of a connection with the Wainer family (Hall and Sowle 1914:8). Historian Norma Judson reported that two historic cemeteries on this section of Drift Road contain members of the Tripp and Eddy families. She also indicated that at least some Wainer family members were buried in the Cuffe cemetery at the corner of Old County and Fisher roads.

Westport’s nineteenth-century Native men appear to have generally followed typical occupations for the period and region. Six are listed as farmers, one as a mariner, and one as a laborer. Thomas S. Boston is recorded as a “daguerreotypist.” Three women are listed as either widows or heads of households, and one 24-year old woman appears as a single entry (Earle 1861). When the First Christian Church of North Westport was established on Old Bedford Road, three pews were reserved for the “Troy Indians,” a name connected with the Native American groups living in the Fall River area during the period (Smith et al. 1976:40).

The early historic period Native American component of Westport’s past represents one of the most important underdocumented resource contexts. Nineteenth-century census data suggests that an active Native community was maintained in Westport, and the identification of extant homesteads from this period would contribute greatly to an understanding of Native lifeways and Native/non-Native interaction in the region. Members of the Wampanoag Tribe likely still reside in Westport, as they do across the region, and are considered to be a primary source of information for the development of additional research contexts relating to Westport’s Native American history.