Jessie Luther (1860 – 1952)

Posted on April 22, 2024 by Jenny ONeill

WOMEN OF WESTPORT POINT

Jessie Luther (1860 – 1952)

Artist, Teacher, Pioneer

15 and 21 Cape Bial Lane, Westport Point

Jessie Luther was born in Providence in 1860, the daughter of Joseph Luther and Sarah Godfrey Luther. She became steeped in the Arts and Crafts movement, studying painting at RISD and traveling to Paris. She was invited to work at the Labor Museum at Hull House in Chicago, considered to be one of the most important of all settlement houses. The concept of a settlement house was established to address the effects of industrialization and the demoralizing effect of repetitive factory work with the power of community, art and creativity. Luther taught metalwork, woodworking, woodcarving, pottery and weaving in order to instill immigrants with a sense of continuity with their past. However, after suffering a breakdown and “worn out by her own enthusiasm” Luther recuperated at The Ark, located in Jaffrey, NH. It was there that she met Dr. Herbert Hall and began to develop her theories of occupational therapy. Luther went on to become director of occupational therapy at Butler Hospital, Providence RI, retiring in 1938.

Luther remained unmarried, perhaps a factor in her ability and willingness to journey to the remote regions of Labrador and Newfoundland.

A Pioneer of Occupational Therapy

By the early 1900s, Luther began to outline her vision for an alternative treatment for mental illness. She felt that “the current treatment known as a rest cure was in many cases a mistake, as a patient should be encouraged to look outward.”

She envisioned an expansion of occupational therapy which had been “for the most part employed … almost exclusively for men, the occupation being brush- and broom-making and gardening. The general establishment of such treatment, however, as applied to women as well as men and in all phases and degrees of nervous as well as mental disorders, is comparatively recent.”

During her career at Butler Hospital, Luther had personally witnessed the success of occupational therapy:

“Although a great many interesting cases and cures have come under my notice, perhaps one of the most remarkable was that of a woman who for three years could scarcely be persuaded to make the least effort and whose interest in basket-making when finally aroused effected a veritable transformation beyond the hope of the most sanguine. In her case her improvement also had its bearing on the other patients in the ward, for her work was really beautiful and original, and her cheery enthusiasm and unlooked-for energy awakened the interest of many new patients in her constant association with them and was of much assistance in carrying on the special branch of work during the interval between class hours. The work was a joy to her, and even before her departure from the hospital became a source of needed revenue.” (Modern Hospital Volume 11, 1918 Chicago IL, Occupational Treatment in Nervous Disorders by Jessie Luther, Butler Hospital, Providence, R.I.)

By 1904, she had joined Dr. Hall to set up an experimental sanatorium known as the Handcraft Shop in Marblehead, MA offering workshops for weaving, pottery, basketry, metalwork, and wood carving. Their patients were those “on the verge of nervous collapse.”

Jessie Luther observed how “persons in a sensitive state of mind are influenced by their surroundings and general atmosphere, it occurred to me that if they could be introduced at once into a workroom where beautiful and interesting things were being produced as a regular routine by normal people who would create a cheerful atmosphere, it would act as an incentive to their own efforts and tend to make them forget their real or fancied worries and their invalid state. To this end four normal, cheerful young girls of the town were engaged and taught weaving and pottery. They were present daily during working hours, and, besides actually producing, assisted the patients as they worked with them. These girls were paid regular wages, and their products, such as woven rugs, table covers, bedspreads, etc., were sold to help defray running expenses. The work produced by the patients was in most cases excellent, and the pride in accomplishment and interest with its attendant benefit practically universal.”

A chance meeting with Wilfred Grenfell at the Handcraft Shop, led to an invitation to create a similar program at the Grenfell Mission located at St. Anthony, Newfoundland “to augment the earning capacity of the people, and to offer interesting and worthwhile occupation as an aid to morale during the idle months of the long northern winter.”

In 1906, at the age of 46, Jessie Luther embarked upon her journey to Newfoundland. To have attempted such a journey as a woman is indicative of her intrepid nature. She spent the next decade developing the Industrial Department at the Grenfell Mission.

Grenfell mats

As an artist, Jessie Luther was struck by the colors and textures of her new surroundings in Newfoundland.

“It is difficult to describe the beauty of winter in this place…the sky at sunset is a curious green near the horizon and the pinks and blues and purples on the snow and ice are beyond description.” (Luther)

She took note of the rugs made by women of coastal Newfoundland, appreciating the workmanship but describing the coloring and design as “very ugly.”

“One summer about nine years ago it occurred to me that if this excellent workmanship could be turned to account by providing attractive, simple designs of a local character, subjects with which the workers were familiar, and substituting coloring that would harmonize with ordinary household furnishings for the crude, nondescript coloring of the native mat, a market could be found outside Newfoundland for the product and the makers paid for their work outright with no responsibility as to material or choice of coloring.”

Thus, Jessie Luther was responsible for redirecting the look and overall design of traditional mats. Her designs were “local in character, reindeer, seal, walrus, ducks, komatik, and dogs, etc., treated conventionally as a border.” By introducing vegetable dyes such as lichen, spruce twigs and bark powder, the overall colors of the mats were softened “to harmonize with ordinary household furnishings” of the typical New England home.

Very few of these early mats based on Luther’s original designs survive. The Mallard Ducks is more typical of later Grenfell mats. In production by 1930, the Mallard Ducks mat was one of the most popular designs. The image was derived from calendar art, a common source for patterns. It shows five ducks flying over marsh grasses, the ocean and rugged mountainous coastline in the background. Subtle gradations of hues suggest a sunset.

Following growing differences of opinion with Sir Wilfred Grenfell, Luther resigned in 1915. However, her involvement with the organization continued as President of the Providence branch of the New England Grenfell Association.

She continued working in the field of occupational therapy as director of the program at Butler Hospital, and she continued the tradition of Grenfell style mats for her RI patients.

“I have given out mats with the same designs here at home, not only to patients of the hospital but to many of the needy Italians and others in this city in need of work that may be done at home to eke out the family earnings. Some of the workmanship has been as satisfactory as that of the north, and among the best is the work of one of the patients, a cut of whose latest finished product is added to this article, while she is fast completing another of a different design.”

Jessie Luther’s Journal

In her later years, Jessie Luther chronicled her experience at the Grenfell Mission. Unfortunately, publishers dismissed the memoir as being too specialized. However, more recently, the journal regained importance as a window into the rural culture of the early 20th century Newfoundland “before the heavy hand of technology arrived.” Edited by Dr. Rompkey, the now published manuscript is notable as a record of everyday life from Luther’s perspective as an artist and as a woman. “So often travel journals in the north are written by men…. you don’t very often get a women’s point of view. She’s interested in such things as what people are going to eat next, how they will be cared for, what is happening with education.” (Rompkey)

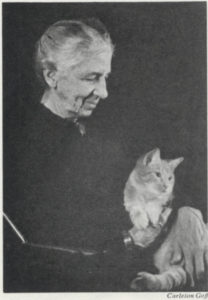

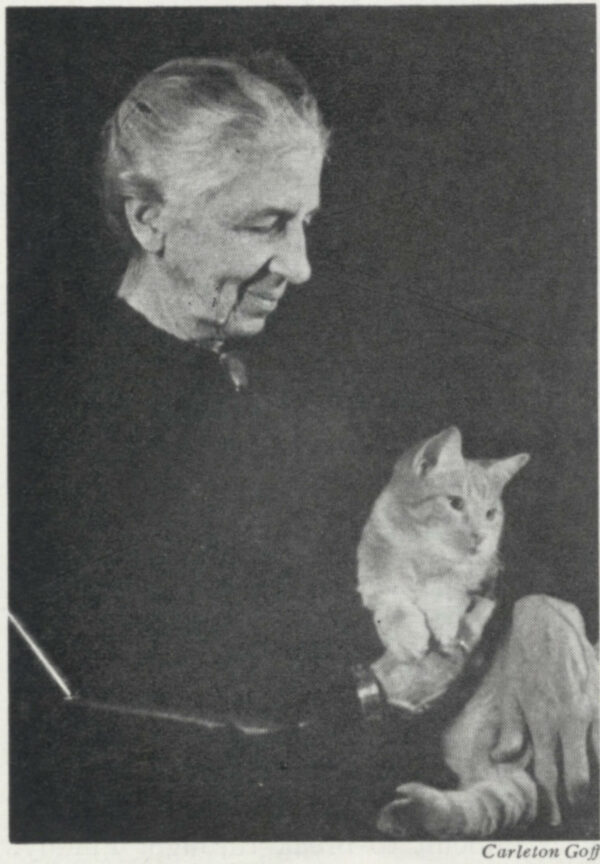

- Jessie Luther and cat

- Jessie Luther at the Grenfell Mission edited by Ronald Rompkey

Jessie Luther’s Westport Years

By 1930, Jessie Luther had built the first of two summer cottages on Cape Bial Lane at Westport Point. Perhaps Westport Point reminded her of the remote coastal villages of Newfoundland.

Traveling between Westport and Providence by bus, well into her nineties, Luther shared her Westport Point home with Clara Buffum, an accomplished bookbinder who was also involved with the Handicraft Club of Providence.

Luther organized sales of Grenfell mats at her home and hosted Wilfred Grenfell at Westport Point. She recalled: “On a beautiful morning I stood with Sir Wilfred in the garden of my summer home at Westport Point, Massachusetts. I can still see his pleased smile as he lifted his eyes to the wide, unbroken sweep of sky and horizon across the garden to the marshes, the salt river, the long line of sand dunes and broad expanse of ocean, brilliantly blue in the early morning sunshine.” (Among the Deep Sea Fishers, volume 39, issue 3 October 1941)

A few snippets of news illustrate her ongoing enthusiasms. In 1923 she invited members of the Appalachian Mountain Club for an “All day outing at Westport Point Mass. Leave Union Station for Fall River at 8 AM. Consolidated train Change at Fall River for New Bedford trolley. Leave trolley at Lincoln Park. Motor bus to Westport Point. Arrive at Providence about 7.30 PM Expense round trip $2.25. Bring lunch, cup and bathing suit. Please notify Miss Luther before July 25 in order to arrange for transportation JESSIE LUTHER.”

To comfort her after the loss of her sister, Jessie’s friends planned to form a small Community Art Center at Westport Point.

Charlotte Fitch, a long-time resident on Cape Bial Lane, Westport Point knew Jessie Luther fairly well. Interviewed in 2008, Charlotte voiced her suspicion, shared by other historians, that Jessie Luther had been in love with Wilfred Grenfell. She also recounted an incident when Jessie Luther fell into the water while trying to board a boat to attend the picnic at Masquesatch. She was rescued by Louis Dexter who, according to Charlotte Fitch, could only see Luther by concentrating on Jessie’s gold beads.” (Remembering Cape Bial Lane, Charlotte Fitch interviewed by Betty Slade, 2008)

- Acoaxet River by Jessie Luther, WHS 2009.010 given in memory of Helen D. Loring

- Acoaxet River by Jessie Luther, WHS 2009.010 given in memory of Helen D. Loring

During her time in Newfoundland, Luther had traveled thousands of miles along the rocky coastline, struggling with sourcing materials, creating markets, and recruiting women. She is also remembered for her career as director of Occupational Therapy at Butler Hospital. Reflecting on her unusual and unconventional life, Jessie Luther attributed her achievements to the following characteristics: “Patience, powers of adjustment, and resignation. With these, one can face the inevitable uncertainties and hazards with a smile.”

Further reading:

Laverty, Paula. Silk Stocking Mats. McGill-Queens University Press, 2005.

Rompkey, Ronald. Jessie Luther at the Grenfell Mission. McGill-Queens University Press, 2001.

Video: A brief history of Jessie Luther and her contribution to arts and health in Newfoundland and Labrador.