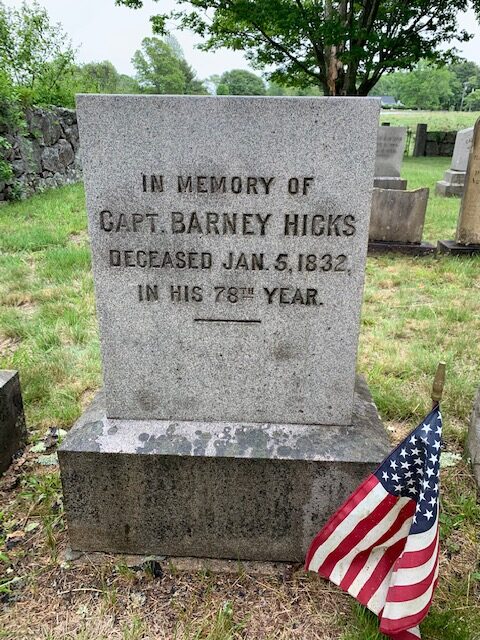

Tarnished Hero: Captain Barney Hicks (1754-1832)

Posted on January 28, 2026 by Jenny ONeill

By Tony Connors

“We have a Sunday wooden leg covered with leather, and for just around the farm, an ordinary wooden one.” (Mary Hicks Brown, interviewed in 1976 about her family history)

When we turn a spotlight on figures from the past, we’re usually looking for people with admirable qualities. What was it that made these men and women exceptional in their time, and perhaps models for our own time? But sometimes we find historical figures to be a complex mix of positive and negative qualities, making evaluation more difficult. Such a character is Westport’s Captain Barney Hicks.

Born in 1754, Barney Hicks reached maturity at the outbreak of the American Revolution. He could have shown his loyalty to the Patriot cause in several ways: by serving in the local militia, engaging in the West Indian trade to bring supplies to the American forces, or by privateering (attacking British shipping – a risky but lucrative endeavor). Instead he chose to enlist in the Continental army. It was a short enlistment; in a few months he returned home and entered the West Indian trade.

This was also risky. The British Navy patrolled the trade routes and assumed that anyone bringing in supplies was a traitor. On his first day out, Barney was captured by the navy. As he was towed to New York Harbor, a winter storm arose during which his ship broke free. Propelled by the storm, the ship ran aground on an island off the coast of New Jersey: Barney Hicks was the only survivor. Fortunately a family on the mainland spotted him and brought him to their home to recuperate. His convalescence took a year, and one foot had to be amputated.

Barney Hicks wooden leg (Little Compton Historical Society)

Once able to maneuver on his artificial leg, Hicks organized a privateer out of Philadelphia. They captured a British merchant ship, took it into a prize port, and with his share of the proceeds Barney was able to reimburse the New Jersey family that saved his life.

Deciding that privateering was both lucrative and patriotic, Captain Hicks fitted out a series of privateers to molest British shipping. But again he was captured, and this time imprisoned in England. More than a year later he was transferred by ship to a British prison in New York, but during the Atlantic crossing he organized a mutiny and brought the ship into Boston where he claimed his privateer’s prize. By this time, despite a great deal of prison time, he was a confirmed privateer – but perhaps not a careful one. Again he was captured, and forced to spend two debilitating years on a prison ship in New York.

When hostilities ended in 1781 (the war officially ended in 1783), Captain Hicks returned to the merchant service, hauling cargo between the Caribbean Islands and New England. In all he made 45 voyages to the West Indies.

His last two voyages are the most interesting, and most troubling.

In 1793 he sailed out of Newport, Rhode Island to Africa, purchased over one hundred slaves, and sold them in Cuba. This was the classic “triangle trade”: carrying Rhode Island-distilled rum to Africa to trade for slaves; selling the slaves in the West Indies; and transporting molasses back to Newport to make more rum. Slavery was still legal in the United States at the time, although illegal in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, as was the African slave trade. In 1794, the slave trade was made illegal by federal law, so Hicks’s second voyage was after that law went into effect.

These two voyages were very successful financially. Captain Hicks was able to retire to his farm and within two months, at age forty, he married Sarah Cook of Tiverton, with whom he had twelve children. Their son Andrew Hicks became one of the wealthiest shipbuilders and whaling agents in Westport Point. Barney died a respected citizen of Westport in his 78th year – a surprisingly long life considering what he had been through.

Barney Hicks House 1603 Main Road Westport MA

If Barney Hicks’s life were shown in a ten-minute video, he would be a hero for the first eight minutes and a villain for the last two. So how do we evaluate his life? Certainly we have to consider the particular conditions and prevailing attitudes at that time, and not apply twenty-first century sensibilities to people who lived two hundred years ago. The slave trade might have been normalized in Newport and Bristol, but it was illegal and immoral even then.

Well before he engaged in the slave trade, Captain Hicks had abetted slavery by trading New England food and building products for slave-produced sugar and molasses. Perhaps that can be chalked up to normal business practice of the time. But it is quite another thing to actually engage in the buying and selling of human beings.

Barney Hicks presents us with a complexity that makes historical evaluation challenging. Does his slave trading outweigh his sacrifices for the revolutionary ideals of freedom and equality? Readers can decide for themselves.

This entry was posted in Westport's Revolutionary Stories.