Native Americans in 19th-century Westport

Posted on June 12, 2020 by Jenny ONeill

“Like the fleeting years and days,

Like all things that soon decay,

Pass the Indian tribes away.”

(Daniel Ricketson, History of New Bedford, 1858)

This lamentation was written by Daniel Ricketson, local historian, in 1858.

Was Ricketson unaware of the many Native Americans living at the time in Dartmouth, whose ancestors had survived war and disease?

How did local Native Americans react to this attempt to write their entire race into extinction?

Local historians of the 19th century devoted much time and energy to lamenting the demise of the Native Americans. Historical narratives eulogizied the “last” Native American and enshrined the end of a “whole race of once powerful and noble people” in poetry and prose. Simultaneously, the government, was busy counting the many Native Americans who remained living in their communities.

Far from vanishing from society, the Native American communities of the Westport-Dartmouth region during the 19th century are distinguished by their story of resilience, resistance and persistence.

Several local factors influenced the 19th century Native American community:

- The absence of any state reservation led to greater integration of property ownership, living and housing arrangements.

- Intermarriage with the African American community reshaped a network of families linked by a common Wampanoag heritage throughout the region, with strong connections to Martha’s Vineyard.

- Adaptation to the economy of the English settlers, especially participation in maritime occupations such as the whaling industry.

- Life stories specific to individual Westport Native Americans who were healers, entrepreneurs, whaling masters, shipbuilders, businessmen, and farmers.

Adaptation: Healers, Farmers, Shipbuilders, Captains

Whaling Master

Reflecting a pattern seen elsewhere in coastal Massachusetts, many Native American men became involved in the maritime industries in Westport and the New Bedford area during the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries.

Pardon Cook (1795-1849) was an accomplished master mariner from Westport. His ancestors were slaves of the Almy and Cook families of Tiverton, Rhode Island. Many of the slaves and free blacks of this area intermarried with Wampanoag Indians. Both groups were socially and economically marginalized and found refuge and community with each other.

In 1839 Cook took the first of his four commands as captain of Westport whaling vessels. He went on to participate in at least eleven whaling voyages, almost all as officer or captain. His legacy includes significant connections to Paul Cuffe through marriage and whaling, and he was a major figure in the extended African American and Native American communities that supported each other to succeed in a society and economy that marginalized them.

Farmers

The Wainer family owned and farmed land in Westport. In 1850 Adoniram Wainer wrote to his brother Asa who was first mate on board the whaling ship Mercator:

“Dear brother,

I take this opportunity to inform you that I and all the rest of us is well hopeing these few lines will find you the same we are very bizy harvesting at this time potatoes about 60 bushells great and small …. corn about 60 or 70 bushells, good corn apples about 25 or 30 bushells got throu digging potataoes, geathered apples, got about throu with our corm. Next is the turnips ….the rest of the pigs is doing well they will weigh 100 a piece.”

Healers

Native American folk healers, often female herb doctors, served their own tribal communities as well as Anglo-American settlers. Folk medicine was regarded as an effective remedy.

Their cures were regarded as secret property and they protected special locations known for roots and plants which were gathered at particular times and prepared in specific ways. For example, roots and herbs were pounded between two stones or beaten in a small wooden mortar rather than by using metal tools. (Gladys Tantaquidgeon, oral history 1930)

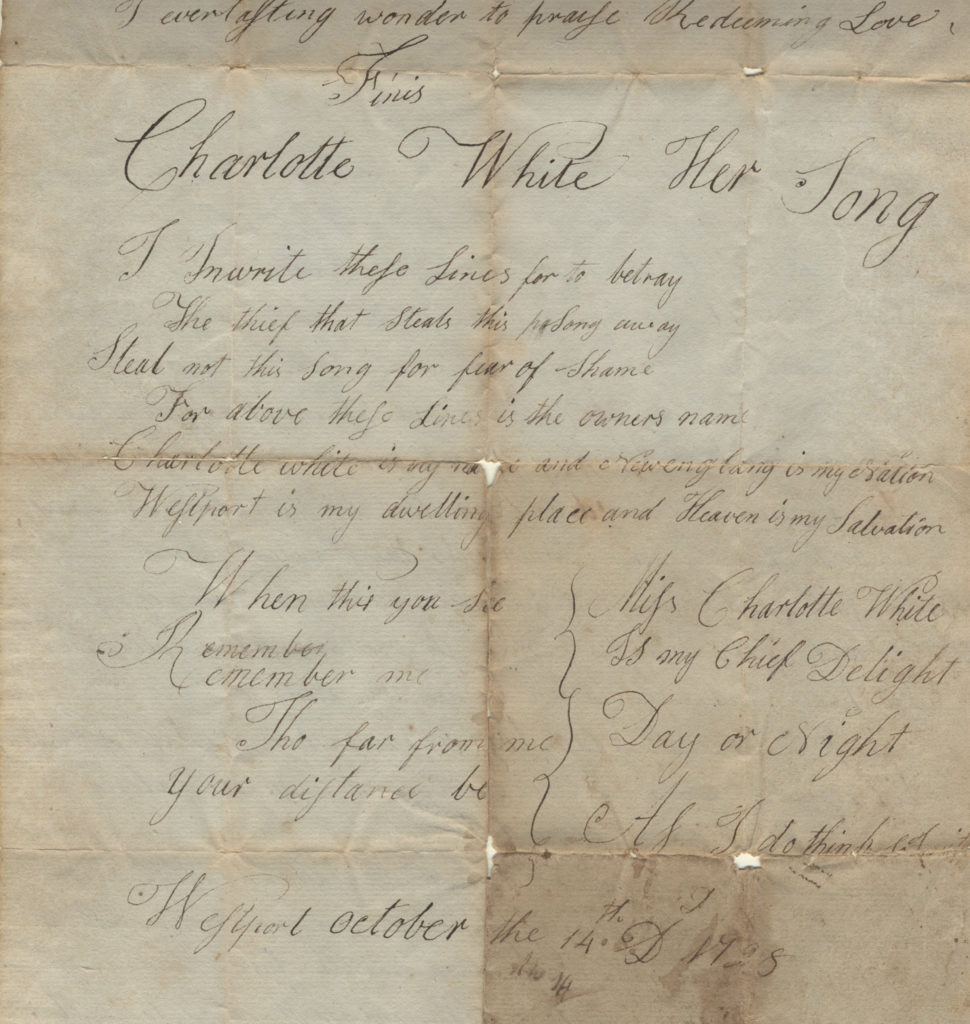

Charlotte White, Indian Doctor

Charlotte White, Indian Doctor

Local histories record the contribution of Charlotte White (1774-1861) as a healer. She is identified as an “Indian doctor” in the census of 1861. Her mother was Native American and her father was a former slave. Charlotte White was involved in poor relief before the almshouse was established in 1824. In the early 1800s she received payment from the town for “nursing and doctoring” a young mother and her baby. The use of the term “doctoring” in the official records gives credence to her reputation as a healer.

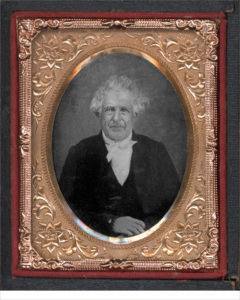

William Perry

Dr. Perry was a prominent herbalist and healer of the Wampanoag community in Fall River and Westport. He tended both Native Americans and the local white communities, divining illness by examining the patient’s fingernails. He treated patients using secret herbal remedies and “performing miraculous cures.” He was described as a psychic and a practitioner of old school Indian belief who attributed his success to the guidance of the Great Spirit. “It was said that Dr. Perry was a wizard and following his death (in 1885) the violin which he owned could never be tuned or played again. He will ever live in the memory of his Indian descendants for the great work of healing.” (Gladys Tantaquidgeon, oral history 1928.)

The Cuffe-Wainer partnership formed a long-term connection of commerce and friendship among Westport’s Native American and African American communities.

By the 1780s, Paul Cuffe had joined forces with his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer, a Wampanoag. Together they established a shipping business, building a series of increasingly larger sailing ships that they used to expand their ocean trading business. Michael Wainer’s sons served as mates, captains and masters of those ships.

In the latter half of the 1790s, realizing the benefits of their successful trading business, both Paul Cuffe and Michael Wainer established permanent residences for their families on nearby properties along the East Branch. Paul built a substantial house next to his shipyard, and Michael Wainer acquired a 100-acre property nearby.

New Networks of Kinship: The Wainer and Cuffe Family

The Wainers formed a community of Wampanoag Indians, many of whom had intermarried with Cuffes and others of African American descent. The Cuffes and Wainers were well known throughout the Dartmouth/Westport/New Bedford region.

The question of identity in the 19th century was complex and fluid as a growing number of Native American women married African American men. By the 19th century, many members of Westport’s indigenous community were children of a Native American mother and an African American father. This demographic shift reshaped and strengthened networks of kinship within the Native American community. Simultaneously, for Anglo-Americans, it confirmed the myth of the “vanishing Indian.”

Anglo-Americans, in their attempt to enumerate the Native American population, had difficulty defining and distinguishing “Indians” from “Negroes.” Local histories and census data placed emphasis on the lack of “real” (pure-blooded) Natives. A broad range of perceived threats to social stability and order informed their unwillingness to acknowledge the persistence of Native American identity.

Within the Native American communities, identity and affiliation shifted across generations and according to individuals. The Cuffe family provides us with an example of this fluidity. Paul Cuffe, as a leader of the African American community remained closely connected to his mother’s and wife’s Native American heritage. His brother, Jonathan, followed his mother’s roots by marrying into Gay Head and becoming a full member of the tribe. Individuals showed a multidimensional sense of self, family and affiliation.

Reclaiming Homelands

“Never been sold, transferred, or alienated, by them or their ancestors”

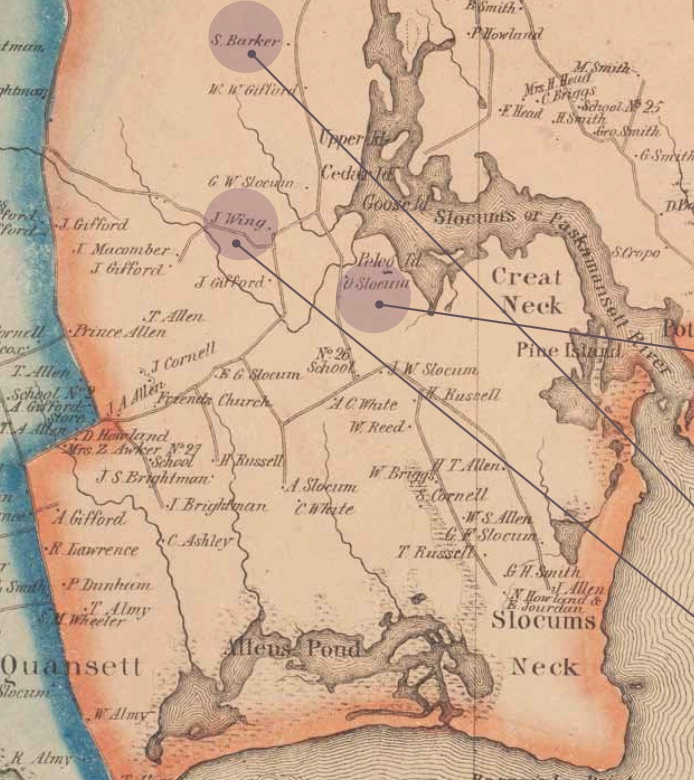

In 1859, the Wainer family and the Westport-Dartmouth Wampanoag community appealed to a New Bedford lawyer to help pursue a land claims case, one of many instances in which Native men who rose to positions to authority aboard whaleships also advocated for Indian rights at home.

The public hearing focused on two tracts of land, one along Slocum’s River, the other near the West Branch of the Westport River, “forme(r)ly owned, occupied, and possessed by said Indians.” The “alleged occupants” of the land by Slocum’s River were Samuel Barker, Nathaniel Gifford, Otis Slocomb, and John Wing, of Dartmouth. Ellery Manchester, Elisha Peckham, and Samuel Brightman occupied the properties by the West Branch of the Westport River.

“I am ninety-one years of age … I knew large numbers of Indians, who occupied lands in this town. On both sides of Slocomb’s River great numbers resided, had their wigwams, and improved their lands as cornfields, hunting and fishing grounds. From nearly a mile south of Otis Slocomb’s house up to north of Samuel barker’s all along the shore on the west side of the river, they lived, had their wigwams and burial-grounds, none of which were ever enclosed by them.”

“I am ninety-one years of age … I knew large numbers of Indians, who occupied lands in this town. On both sides of Slocomb’s River great numbers resided, had their wigwams, and improved their lands as cornfields, hunting and fishing grounds. From nearly a mile south of Otis Slocomb’s house up to north of Samuel barker’s all along the shore on the west side of the river, they lived, had their wigwams and burial-grounds, none of which were ever enclosed by them.”

(Marlborough Wood testifying at the public hearing, 1859.)

“I am eighty-eight years of age… I knew in my early years of Indian lands and Indians occupying them, in Dartmouth, from north of Samuel Barker’s, all along the shore, including two burial-grounds. Particularly do I remember Nehemiah’s place–his orchard and farm; from his orchard have I taken apples. He was celebrated as an Indian minister. The place now occupied by John Wing, the north part of which was an Indian settlement called “Quanachee.” (Samuel Wilcox testifying at the public hearing, 1859.)

“My great-grandmother was buried in the burying-ground on Otis Slocomb’s farm, and lived and died near there. She had a wigwam there, and it was the last one there.” (Deborah C. Borden testifying at the public hearing, 1859.)

“I reside in Westport. I remember my grandmother. Her name was Margaret Quebbin. She was a full-blooded Indian. She lived, part of the time in Dartmouth, and part of the time in Westport. She lived about a mile and a half west of Slocomb’s River in Dartmouth, near where Naomi Quance lived. My great- grandmother was Dorcas Quebbin. She was reputed to have lived down by Slocomb’s.” (John Wainer testifying at the public hearing, 1859.)

“I am sixty-eight years of age. I recollect the mother and grandmother of Rodney Wainer, and where they lived. The grandmother lived on land recently occupied by Abraham Manchester, about a mile from the sea, and near a mile from West River. About a mile further north, near the river, an Indian lived, named Jacob Howdy. It might be thirty years since, more or less. Rodney’s mother lived a little way across the line, in rhode Island. It was generally reputed that these were Indian lands.” (Charles Manchester testifying at the public hearing, 1859.)

“Indians of the Commonwealth”

The Earle Report, 1861

The presence of Native people in 19th century Westport is documented in the 1861 Earle Report, commissioned to collect census data about indigenous Massachusetts residents. “Dartmouth Indians” are listed as those persons belonging to the Wampanoag Tribe who were in earlier times known as the “Acushnets, Acoaxets, and Aponegansets.”

Following King Philip’s War, Native Americans who had fought on behalf of the colonists remained in the south coastal area, and missionaries who visited Little Compton in 1698 were said to have reported two separate communities, one at Sakonnet and the other at Acoaxet (or Westport), each with their rulers and teachers.

The accuracy of this census is questionable. Census taker John M. Earle admitted his own failure to gather comprehensive data. Furthermore, Anglo-American prejudice was expressed in the inability or unwillingness of white observers to define or recognize who should be counted.

The census recorded:

- 111 Dartmouth Indians within 29 families.

- 99 persons were listed as “Natives.”

- 12 were listed as “Foreigners and unknown.”

- Nearly half of the total population was between the ages of 21 and 50.

- 50 of the 111 Dartmouth Indians are Westport residents. These individuals include members of the Crouch, Cuffe, Marston, Nicholson, Phelps, and Wainer families.

- Most of the Westport Native American families appear to have been landholders.

- Charlotte White is recorded as an 84-year old “Indian Doctor” with 11 acres of land.

- Occupations include farmers, mariners, sailmaker, laborer, daguerreotypist.

- Sylvanus Wainer is listed as a miner, residing in Australia.

Living Among Native Americans

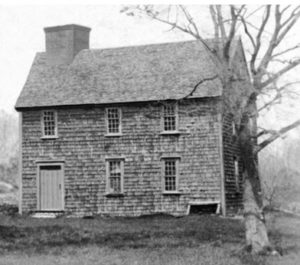

The Handy House was built c.1712, nearly 40 years after King Philip’s War.

How might its Anglo-American occupants have viewed their Native American neighbors?

Elizabeth White, who lived here in the 1700s, was personally connected to the war through her great-grandparents, John and Sarah Warren Cooke. Their home was used as a garrison house during the conflict, putting the couple on the front lines of battle. However, during her lifetime, Elizabeth lived peacefully among Native Americans who remained in this area, with settlements on the West Branch of the Westport River and near Slocum’s River. New Native American families relocated to this area; Cuff Slocum, an emancipated slave from West Africa, and Ruth Moses, a Native American woman from Cape Cod purchased a farm a few miles from this house in 1767.

Into the mid-18thcentury, the White family, who owned a number of slaves, provides us with an example of the networks created by the intermarriage of enslaved people with local Wampanoags. In 1765, Zip White, a slave owned by the White family, married a Wampanoag, and settled in a house on what is now Charlotte White Road. Their daughter Charlotte White, was recognized locally as an “Indian doctor.”

The account books of Dr. Handy, who lived here in the 1800s, include the names of many members of the Native American community whom he treated for a variety of illnesses, either here at this house or by traveling to the patients’ home. He delivered the babies of Native American mothers, he treated illnesses of Native American healer, Charlotte White and cared for Paul Cuffe and his family.

If you would like to learn more about the Native American heritage of this region:

Suggested reading:

- Behind the Frontier by Daniel R. Mandell

- Tribe, Race, History by Daniel R. Mandell

- Firsting and Lasting by Jean M. O’Brien

- The Wampanoag Genealogical History of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts (Two Volumes) by Richard Andrew Pierce and Jerome D. Segel

- Spirit of the New England Tribes by William S. Simmons

- Living with Whales by Nancy Shoemaker

- www.PaulCuffe.org

- Research by Richard Gifford and other resources available on the Dartmouth Historical and Art Society website www.dhas.org