The Washingtonians and the Nineteenth-Century Temperance Movement in Westport

Posted on June 16, 2010 by Jenny ONeill

Temperance – the campaign to curtail the consumption of alcohol – was an important reform movement in the 19th century. Westport had a number of active temperance groups, and one of the most effective and controversial was the Washingtonians, who shot to prominence in 1840, only to be crowded out by competing abstinence groups by mid-century. Their building at the Head of Westport, Washingtonian Hall (c. 1842), still exists near its original location. This presentation relates the story of the movement as it transformed into Prohibition in the 1920s, and how the building has adapted to change over the past 170 years.

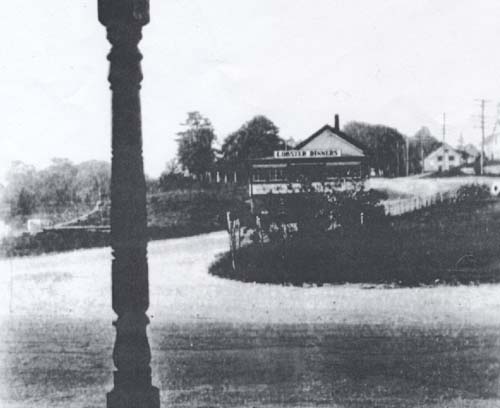

Washingtonian Hall shown here in its original location, circa 1900

WHS collection

The temperance movement against alcohol abuse was not a holdover from the Puritan era. The classic definition of Puritanism is the fear that someone, somewhere is having fun; but even Puritans drank. It is recorded that when they arrived in Boston 1630 they brought with them 12 gallons of distilled spirits, 10,000 gallons of beer, and 120 barrels of brewers malt.

To understand Temperance it must be seen as part of the general reform movement of the early 19th century that included prison reform, hospitals for the insane, cleaning up slums, anti-slavery, and various other ways to improve American society. While drinking was (and is) considered sociable, democratic, and egalitarian, it was also recognized as a serious social problem: it has been estimated that in the early 1800s, alcohol consumption per capita was 2.5 times what it is today. Broken homes, child and spouse abuse, lost jobs, crime, and early death were all serious alcohol-related problems.

One reason for the increase in drinking was the availability of hard liquor, such as rum and whiskey. There were many distilleries here in Massachusetts producing rum from molasses brought in from the West Indies. Dram shops, selling hard liquor by the shot, were everywhere. The increase in wheat production also lowered the cost of whiskey: rather than make flour, it was often more economically advantageous to turn it into whiskey. Even George Washington had a large distillery at Mount Vernon, and made a tidy profit from his whiskey operation.

Another founding father, Thomas Jefferson, took a dim view of hard liquor, or “ardent spirits,” as it was called. Like many early temperance advocates, Jefferson promoted the consumption of wine and beer as a substitute for rum and whiskey. (In fact it was commonly believed until the 1820s that fermented drinks like beer and wine did not contain the same alcohol as whiskey or rum.) “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap,” Jefferson wrote in 1818, “and none sober, where the dearness of wine substitutes ardent spirits as the common beverage.”

The temperance movement of the early 19th century was part of the larger attempt to reform prisons, schools, slums, and slavery. Much of this was based on the “perfectionist” idea that humankind can be improved. During the Second Great Awakening, many Evangelical Christians came to believe it was their duty to make the world better. Some believed in the “premillennial” idea that Christ’s Second Coming would only only after the world had been greatly improved: therefore it was a religious duty to be actively engaged in reform.

But this was not exclusively a religious movement. We can see evidence of civic efforts to reduce or control drinking here in Westport, as the 1818 town records show:

A Committee to calculate the probable expense of supporting the poor in a work house, etc: Peleg Sisson, Abner Brownell, Barney Hicks

VOTED that said Committee be directed to ascertain the number and names of those paupers who are now on expence and who are likely to become so by idleness, dissoluteness or intemperance & who in their opinion ought to be sent to, and employed in such an house.

The Temperance Movement became formally organized with the creation of the Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance in 1813. This early temperance effort was characterized by elite members – wealthy town leaders, Congregational and Unitarian ministers – trying to control the behavior of an intemperate public. The elite were convinced that drinking was a lower class problem, and made no effort to control their own social drinking. The lower class had no interest in being controlled by their economic and social superiors, and the Massachusetts Society faded from existence in less than ten years.

But the reform movement itself did not die out, and in 1826 a national temperance society was organized. Headquartered in Boston, the American Temperance Society (ATS) was evangelical in nature, and closely tied to churches. By 1835, there were 8,000 affiliates and 1.5 million members. And by 1836, the society no longer tolerated moderate drinking of wine or beer. The aim was now total abstinence from alcohol, known as “teetotalism.” Like earlier temperance efforts, the ATS emphasized prevention, not help for those who had alcohol problems. As one temperance leader starkly phrased it, the goal was to “keep the temperate people temperate; the drunkards will soon die, and the land [will] be free.”

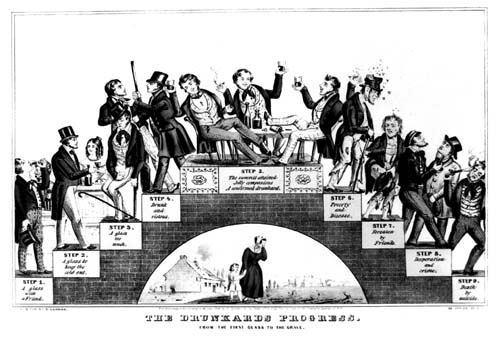

The American public was very much aware of the evils of alcohol due to the sensational literature and lurid images distributed by temperance organizations. One of the most famous images is The Drunkard’s Progress from the First Glass to the Grave (1846) by Nathaniel Currier (of Currier and Ives fame)

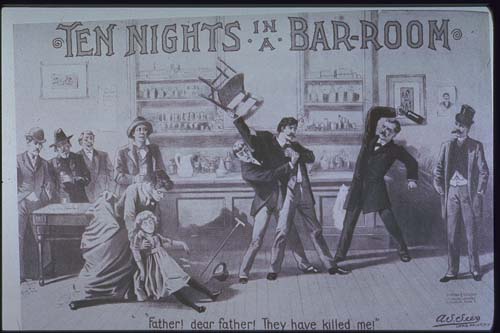

A play called Ten Nights in a Bar-Room, by Timothy Shay Arthur (1854) was very popular.

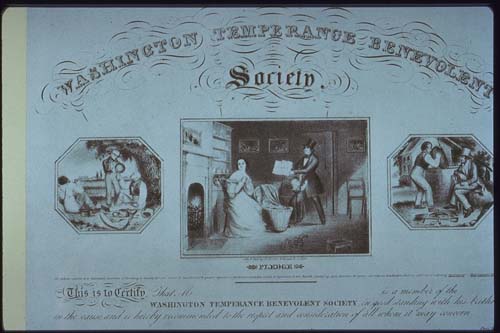

Into this context of public awareness and organizations to reform lower-class society came the Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society. In 1840, six drinking buddies from Baltimore agreed on a self-reform program that was by and for problem drinkers. They chose the name Washingtonian because of its obvious connection with the revered first President (probably unaware that George Washington was a whiskey distiller). The main component of their program was the “experience speech” of a reformed alcoholic, as opposed to the respectable lecture of the more traditional temperance organizations. The society was wildly popular: by 1841 there were 200,000 members, and two years later there were over one million.

Among the supporters of the Washingtonian method was Abraham Lincoln, who gave a speech to the Springfield (Illinois) Washingtonians on Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1842. To Lincoln, the Washingtonians were more “Christian” than many church-run temperance societies because they emphasized the sufferer. Lincoln was also attracted to the Washingtonians’ avoidance of legal measures: persuasion and reason were the keys to reform.

The Washingtonians were very different from the other temperance societies of the day:

• Emphasis on helping problem drinkers

• Financial support for families

• Women played an important role – Martha Washington Societies

• No prayers, no preaching

• The “Experience Speech” – frank talk by a reformed drinker

• Minstrel shows, comedy, rough talk – “taverns without alcohol”

• Sponsored picnics, parades – “a popular culture of temperance for working class people”

An indication of the rapid growth of the Washingtonian Society is the fact that they established a local branch here in Westport in 1842. Washingtonian Hall was erected in 1842 over the old saw pit on the Town Landing (across Drift Road and a few hundred feet north of the Bell School).

Washingtonian Hall from the north

WHS collection

The funding was provided by a joint stock company, whose primary members were George H. Gifford, Charles B. Hayden, Ezra Macomber, Moses Macomber, Jeremiah Thomas, Thomas W. Baker, and William Tabor (there were about 25 shareholders in all). The total cost of the building was $280. To defray expenses, the building was rented out for other meetings, including religious services in 1850s.

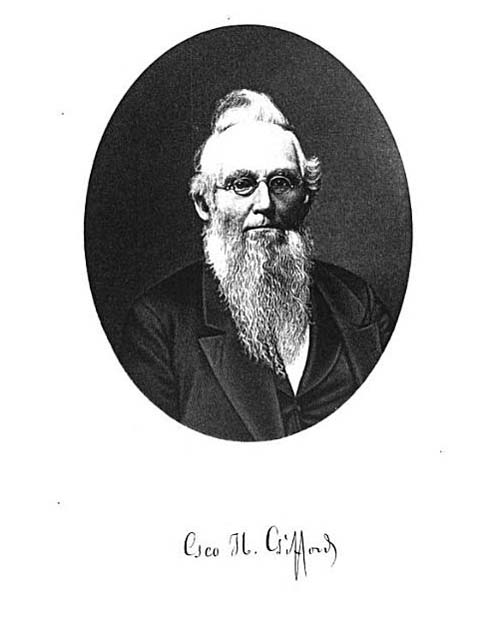

The Westport Washingtonian Society member we know the most about is George H. Gifford

George H. Gifford

Gifford (1806-1882) was a teacher, farmer, whaler, carriage-maker, justice of the peace, selectman, treasurer, town clerk, and state representative. He was the kind of respectable, well-connected citizen that a local society would want to have on its board of directors, but there was a problem: George was a drinker and did not want to take the abstinence pledge. But the society members convinced him, and he was elected vice-president of the society. Once he took the pledge he became a zealous temperance advocate, and was known as the “Old Temperance War-Horse.” As one nineteenth-century biographer noted, “He fought the Rum Demon everywhere and at all times.”

One more anecdote about George Gifford: As a Judge who also liked to cook, he often provided delicious meals for the lawyers waiting to appear in court. But those representing liquor interests were served only dry crackers.

Despite its meteoric rise, the Washingtonian Society began to fade by the mid-1840s. There was competition from newer middle-class temperance organizations with an emphasis on respectability. They portrayed the Washingtonians as vulgar, while ministers (outraged that the Washingtonians did not look to them for leadership) branded them as anti-religious. The new organizations also placed more emphasis on legal prohibition of alcohol. As the well-known reformer Lyman Beecher bluntly put it, “their thunder is worn out. The novelty of the commonplace narrative is used up, and we cannot raise an interest. . . .”

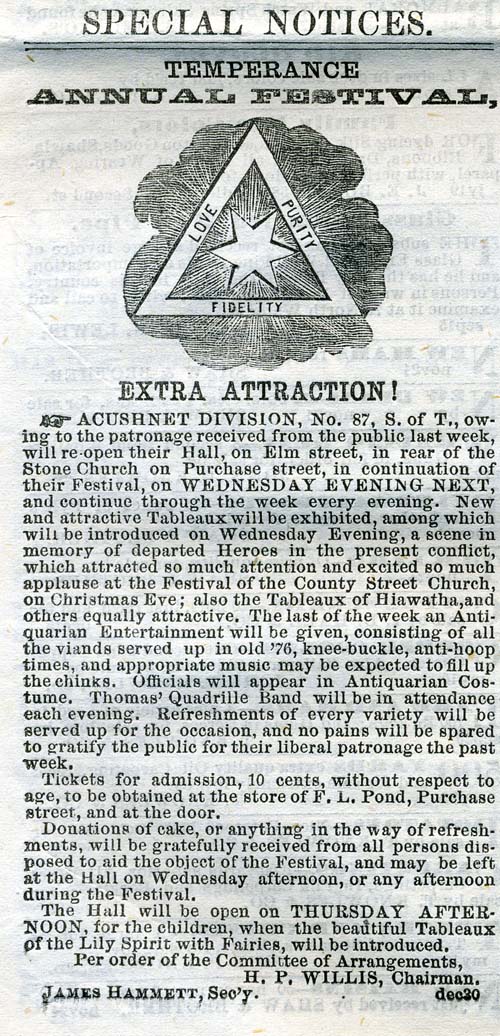

One of the more successful of the new temperance societies was the Sons of Temperance

which opened the Noquochoke chapter in Westport in 1859.

The Sons of Temperance were similar to the Masons, with elaborate rituals and regalia (there was a Daughters of Temperance as well). One thing they borrowed from the Washingtonians was an emphasis on mutual aid. Many of Westport’s respectable citizens were drawn to the Sons of Temperance – including George H. Gifford. Others joined the many competing organizations, such as the Rechabites, Good Samaritans, and Good Templars.

All this moral reform had worked to some degree. Alcohol consumption had definitely dropped, and the public was more generally aware of the problems related to drinking. Sobriety became a fixture of middle-class respectability. Yet drinking and its associated problems persisted, due to immigration, crowded cities, and harsh working conditions, among other factors. More temperance societies began to place increased emphasis on legal prohibition. Portland mayor Neal Dow – known as the “Napoleon of Temperance” – was able to impose prohibition in Maine in 1851, and by the mid-1850s all New England states were dry. However, this was short-lived because temperance was overshadowed by the anti-slavery agitation of 1850s and the Civil War.

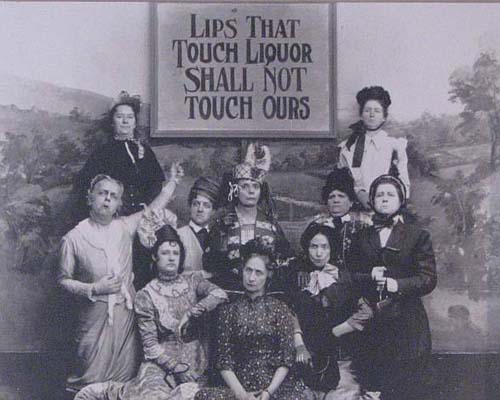

After the war, temperance zeal picked up again with greater emphasis on legal and political prohibition. The Prohibition Party was formed in 1869 and competed in the 1872 national election. At its peak in the 1890s the party garnered 270,000 votes for its presidential candidate. (The Prohibition Party still exists, but now it is tiny, ultra-conservative states’-rights group.) More effective, particularly at the local and state level, was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

Often mocked as a bunch of dour old biddies, they proved to be well organized and politically astute. Although its members were unable to vote, the WCTU was able to exert pressure and influence on the men in their lives. One famous WCTU poem was called “Lips that Touch Liquor Will Never Touch Mine”:

The Demon of Rum is about in the land,

His victims are falling on every hand,

The wise and the simple, the brave and the fair,

No station too high for his vengeance to spare.

O women, the sorrow and pain is with you,

And so be the joy and the victory, too;

With this for your motto, and succor divine,

The lips that touch liquor shall never touch mine.

A local chapter of the WCTU was active in the Westport area well into the 20th century.

A particular target of late 19th century temperance societies was “saloon culture” – men drinking in bars. One critic referred to saloon culture as “the acme of evil, the climax of iniquity, the mother of abominations, and the sum of villainies.” In 1895 the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) was formed, and despite the wild image of the hatchet-wielding Carry Nation, the League was highly disciplined and effective.

The work of groups such as the WCTU and ASL, along with the cumulative effect of decades of reform, Progressive era beliefs in reform, and the particular conditions of WWI, resulted in national Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment was ratified in 1919 and took effect in January 1920.

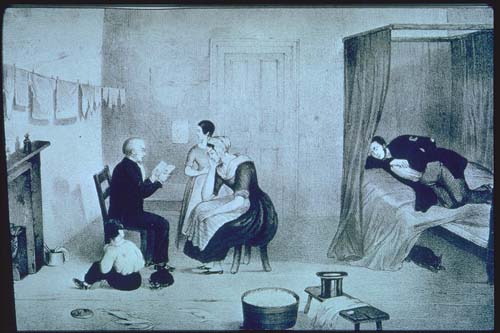

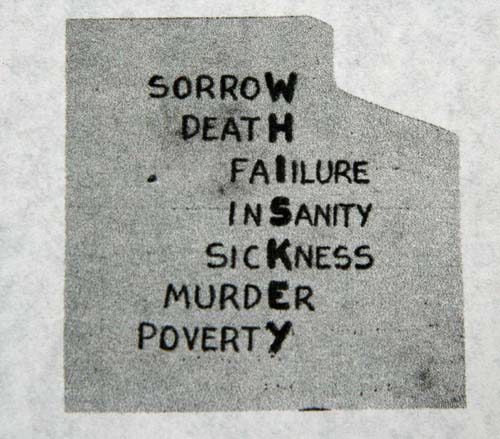

The Prohibition era is beyond the scope of this presentation; suffice it to say that prohibition encountered legal limits and was impossible to enforce effectively. Repeal came in December 1933. However, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union remained active in Westport (Cukie Macomber recently donated his mother’s WCTU cookbook to the Westport Historical Society; and in the papers of long-time Westport resident Dorothy Curtis I found a diagram associating whiskey with death, insanity, murder, and poverty).

Dorthoy Curtis collection, WHS

The WCTU still exists, actively working against alcohol, drugs, tobacco, and gambling.

What happened to Washingtonian Hall after the demise of the Washingtonian Society? Sometime before 1880 it became known as Riverside Hall.

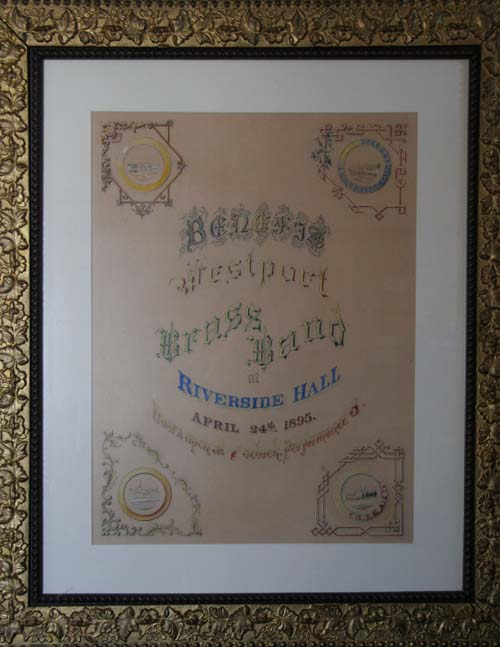

Riverside Hall poster, WHS collection

(The Historical Society has the notice for a play called “Red Riding Hood’s Rescue, or the Dangers of Disobedience” performed at Riverside Hall in June 1881.) In the late 19th century it was owned by George E. Gifford, who rented it out for dances. Later it was sold to a wheelwright who operated a shop for many years. From 1929 to 1935 it was owned by David Allen, who operated a tea room and ice cream parlor

Keeping in mind the building’s temperance heritage, it is noteworthy that its next owner, Arthur M. Reed, got approval from the Westport Selectmen in 1935 to open it as a tavern. However, the Landing Commission was opposed (the building was on town land), so Reed moved it a few hundred feet to the north. The tavern closed shortly thereafter because it was considered “too rowdy.” The original Washingtonian Hall is currently a private home, on the banks of the Westport River on Old County Road.

Washingtonian Hall, now a private residence located on Old County Road

And what happened to the Washingtonian idea? In June 1935, shortly after repeal of Prohibition, Alcoholics Anonymous was founded. There are striking similarities between AA and the Washingtonians:

• Total abstinence from alcohol

• Drinkers helping each other

• Sharing of experience (rather than professional speakers)

• No religious affiliation (but reliance on “higher power”)

• No resort to legal prohibition

So the 1842 building lives on. And the Washingtonians are not just a footnote to history, but rather a historically important reform group whose ideas still have meaning in the 21st century.

Written by Tony Connors