Agricultural Activities

Posted on June 28, 2014 by Jenny ONeill

The development of early Westport included the creation of Euro-American farms on large tracts of fertile land in the southern section of town. Following a pattern seen in other coastal New England towns, settlers likely chose lands that had been cleared and cultivated by Native Americans during the Woodland and Contact periods. The reports of Native cornfields along the necks and riverbanks of Dartmouth suggest that similar areas in Westport would have been desirable to new Euro-American residents who were eager to establish homes and farmsteads (Herbster and Cox 2002).

Early Euro-American settlers also took advantage of the many tidal islands located along both branches of the Westport River as pasture for cows, sheep and other livestock. Animals were herded out to the islands at low tide and were safely contained as the water rose. Linnikin Island (depicted on the USGS map as Corys Island) is located just north of Horseneck Point (N. Judson, personal communication 2003). Linnikin was used for farming as well as pasture, suggesting that other islands in the Westport River and Harbor were utilized for agriculture throughout the historic period. Extant records for the island, which contained 6 acres of upland and 6 acres of marsh, provide information about coastal farming in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Deeds indicate that Linnikin was sold from one local family to another throughout the eighteenth century, and divided into two parcels in 1784. An account entry for 1844 describes payment for men and oxen to remove manure from the island on a scow, spread manure and seaweed, plow and plant corn. Payment was also made for “Digging stones after the plow” and removing 11 loads of rock. Profits from farming the island were made from both corn and pumpkins; the former producing 100 bushels (Hall and Sowle 1914:10–11).

While the town’s village centers developed commercial, industrial, and civic institutions, residential patterns tended to fill in along the existing roadways that linked one area to another. Farmsteads were developed on land holdings along theses corridors, with a homestead often built near the roadside. While early statistics are unavailable, it is clear that the majority of the town’s food and raw materials were produced on family farms during the eighteenth century.

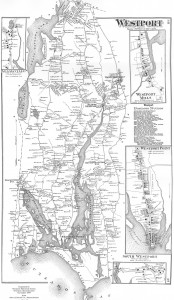

The 1830 map of Westport depicts areas of “cleared land” in Westport, and can be used to identify general patterns in farming during the early nineteenth century. Large portions of southern Westport appear to have been cleared, including the entire east bank of the East Branch and most of the west bank, the area surrounding Westport Point, Acoaxet, and much of the east bank of the West Branch. The Horseneck peninsula includes a mix of meadow and woodland, and the majority of the land north of the Head is depicted as wood lot. Large cleared parcels are depicted along the major roadways and likely indicate family farmsteads that could have been present in the eighteenth century as well.

The entire Horseneck peninsula was kept as common grazing land for the town well into the nineteenth century. A town record from 1800 ordered that no meat cattle or horses were to run at large on Horseneck, and a 1910 Board of Health reports cites the elimination of “p

igs, manure and swill from Horseneck Beach” as a goal (Ledoux 1995:4, 31).

Cranberry cultivation was also practiced in Westport in the nineteenth century. Several large businesses were located in the coastal zone, especially in the area surrounding the harbor at Westport Point and Horseneck Beach. An 1860 record lists “good” cranberry lots for sale at Upper Horseneck for $5 to $20 per acre (Smith et al. 1976:10). The 1871 map of Westport depicts three separate Gifford family cranberry businesses south of the Point on Horseneck Beach.

Many of Westport’s farms have been active throughout most of the historic period. One example cited in the documentary record is typical of the nature of family farming in Westport. Oscar Palmer, born in 1884, lived his entire life of 92 years on his family’s dairy farm on Adamsville Road. The house he lived in had been built around 1700 and was likely continuously occupied into the modern period. Palmer’s grandfather Henry had purchased the farm property from Nathan Brownell in 1855 (Maiocco 1995:14).

Portuguese families have also been Westport farmers for generations. The Medeiros farm was established by an Azorean immigrant who arrived in Fall River in 1900. Brothers Manuel, Joseph, and John Medeiros rented out land in Westport to raise dairy cattle and operated a milk delivery service to Fall River. The family bought land on Sodom Road in 1918 and by 1921 had established the prosperous High View Farm (Maiocco 1995:15).

Census records indicate the importance of agriculture to the town’s economy throughout much of the nineteenth century. The 1820 census lists 435 of the town’s 2,600 residents as “engaged in Agriculture,” more than four times the number employed in other pursuits such as commerce or manufacturing (Jackson and Teeples 1976). The Massachusetts census of 1855 provides information about occupations by county, rather than by town, so it is difficult to gauge the actual numbers for the town of Westport. Using the county data as a general guide, agriculture is listed as the second-most numerous occupation after the category of laborer, with more than 5,000 men countywide engaged in farming as a primary occupation (DeWitt 1857). In 1875, 616 of Westport’s 918 working men listed their occupation as either “farmer” or “farm laborer” (Smith et al. 1976:38). Town records from 1890 list 467 farmers out of Westport’s total population of 2,599 residents. By way of comparison, 199 men were listed as sailors in the same census (Ledoux 1995:5).

One of Westport’s more famous agricultural products is the Macomber turnip. Israel Macomber’s farm was located on Main Road in the 1850s and his sons produced the hybrid vegetable in the 1870s by crossing yellow turnips with locally grown white radishes. Local farmers across the town grew this sweet turnip, which was extremely popular in the 1920s.

There were reportedly more than 400 operating farms in Westport at the turn of the century (Ledoux 1995:51). Historian Frank Hutt described Westport in the 1920s as a place where “farming, poultry raising and fishing are the industries of the town. A large proportion of the farms are productive and well located for market-gardening” (Hutt 1924:822). Hutt named the farms of Edmund Gifford, Nelson Gifford, Frank Perry, John Costa, Nason Macomber, William Hicks, Joseph Bone, and John, George and William Smith as being present at the time of his research.

Archaeological research about historic farmsteads in the southern New England area is lacking primarily because of the dearth of unaltered farmland in the present day. Westport presents a unique opportunity to document a number of extensive family farms that date back as far as the seventeenth century. Coastal historic farmsteads are generally rare in the region as much of the land was developed into suburban or resort housing in the modern period. Many of the original elements, including homes, barns, wells, privies, pens, smoke and milk houses, and shops may survive as either standing structures or belowground features within parcels that have been maintained throughout the years.

Westport’s historic farmsteads and agricultural lands also contribute to the setting of the East Branch historic landscape corridor (Adams et al. 2001). Farmlands on either side of the river are generally considered to have a high sensitivity to contain both prehistoric and historic period archaeological resources.